When Ira “Big Mac” McConaughey died in 1936, news of the famed flier’s death was carried in major newspapers across the country from New York City to San Francisco. Born at Deerfield to James C. and Emma McConaughey, Ira had made a habit of making headlines.

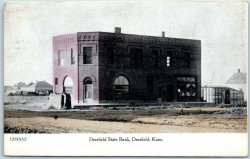

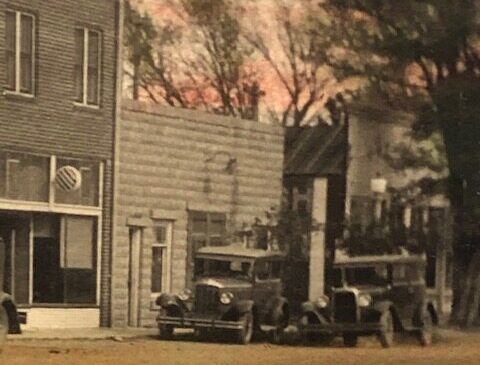

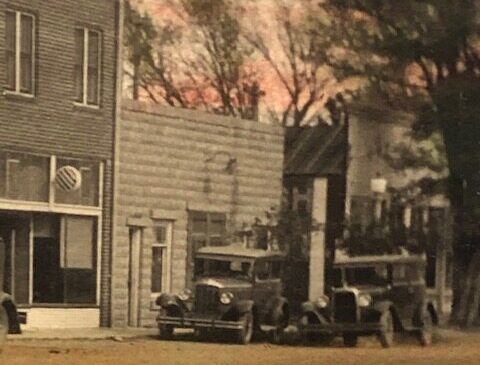

Ira was in the automobile repair business at Deerfield with Bill Bechtel prior to entering the Navy in 1918. McConaughey served aboard the U.S.S. Cacique, a freighter leased by the United States Navy to transport Allied personnel and cargo to France in support of the European fighting front during World War I. After his honorable discharge in 1919, he returned to Kearny County and once again engaged in the garage business with Bechtel. Their Santa Fe Garage opened in 1920, and in addition to repairing vehicles, the proprietors also sold automobiles, gas, parts, and tires. The business was located on the east side of Deerfield’s Main Street and later became the sight of Santa Fe Motors.

Even before he was a pilot, Ira made the local news for his prowess behind the wheel. In June of 1920, the Advocate reported that he was a speed king, “eating breakfast in Kansas City, dinner in Wichita and supper in Deerfield. What is the need of an airplane, when a Ford makes these things possible?”

But Ira soon caught flying fever. The Angel Flying Circus was the main attraction each day of the 1923 Kearny County Fair, and less than a month later, Ira and Fred Fulton purchased their own plane from Jimmy Angel who taught them how to pilot it. Before long, Ira was performing with the flying circus at fairs and air shows. His name was consistently in the local papers from that time on.

In March of 1924, Ira was piloting when a crippled Angel plane crashed into a willow tree break near Dermott, Arkansas. Ira and passenger “Sailor Jack” Lewis were only injured, but star acrobat Mildred Bennett was killed instantly. Bennett, 18-year-old Hardtner, Kansas native, was the first woman to transfer from one plane to another while in mid-air, a feat she first accomplished at Kearny County’s 1923 fair.

In May of 1924, the Advocate reported that, “Ira McConaughey was here Tuesday visiting his parents and his arrival was out of the ordinary way, having arrived in his air plane, the first bird man ever to visit relatives and friends in Lakin, by this kind of conveyance.”

By July 1924, Ira was at Texarkana, Texas, and in charge of the flying field there. That October, the Advocate carried the news that he had flown from Texarkana to Dayton, OH, in nine hours, “a most remarkable record” for that time.

Before long, McConaughey was making the national papers. In 1928, he won the free-for-all event at the Newton, Kansas air races with an experimental plane developed by Walter H. Beech of Travel Air Manufacturing (later Beechcraft). In 1929, Ira flew the mystery ship to a world’s speed record of 235 miles per hour for land planes. When Big Mac performed at the Kansas City air races in 1929, the Kansas City Star said he “has traveled faster than any man who ever percolated through the upper reaches of the stockyards.” According to the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Ira’s speed record was not broken until about a month before his death.

McConaughey also worked for Swallow Company, Riesser Company, Travel Air and Universal Airlines, and he was chief pilot and operations manager at Central Airlines where he flew a regular run between Wichita and Tulsa. In 1931, he moved to Dallas and became a pilot for American Airlines.

In September of 1932 when three army airplanes failed to locate a crashed airplane in the Guadalupe Mountains, it was Ira who located the wreckage. McConaughey was dispatched from Dallas to hunt the plane and sighted it; then, he landed at the emergency field and returned to the downed plane in a borrowed automobile. Again, Ira’s name made national news.

Ira died in a Dallas hospital on September 26, 1936, after a brief illness. He was 41 years old and left behind his wife of five years, Mary Francis; his mother, two brothers and two sisters. Ira “Big Mac” McConaughey had logged more than 12,000 hours in the air, or approximately 1,500,000 flying miles.

SOURCES: History of Kearny County Vol. II; archives of The Advocate, Wichita Evening Eagle, Wichita Eagle, Sylvia Sun, Kansas City Post, Tulsa Daily World, Atlanta Journal, Washington D.C. Evening Star, New York Daily News, San Francisco Examiner, Fort Worth Star-Telegram, and Dallas Morning Star; Ancestry.Com; Wikipedia; and Museum archives.

Free and cheap land enticed more than one million people into Kansas by 1890. The Homestead Act allowed settlers to claim 160 acres of public land by paying a small filing fee, building a residence, growing crops and living on the land for five continuous years. Filers could also purchase government-owned land for $1.25 per acre after living on it for six months, building a home and planting crops. The head of the household or any citizen or person intending to become a citizen was eligible to claim land. An 1864 amendment allowed a soldier with two years of service to acquire the land after a one-year residency.

Over 80 million acres of public land were distributed through the Homestead Act by 1900. Under pre-emption law, no more than 160 acres could be obtained by one person, but that changed in 1873 with The Timber Act which allowed homesteaders to get an additional 160 acres if they set aside 40 to grow trees. The intent was to solve the lack of wood on the Great Plains. After planting the trees, the land could only be completely obtained if it was occupied by the same family for at least five years.

Many other settlers came to Kansas by way of Railroad Land Grants or School Land Grants. Desiring a transcontinental railroad, the U.S. Government gave public lands to railroad companies in exchange for building tracks in specific locations. Railroads were then able to sell their excess land to settlers looking for new homes. From the late 18th century through the middle of the 20th century, the federal government granted control of millions of acres of federal land to each state as it entered the Union with the stipulation that proceeds from the sale or lease of the land be used to support various public institutions—most notably, public elementary and secondary schools and universities. Persons over 21 years of age could settle on a quarter section of school land, live on it for six weeks, and pay just $3 per acre. That cost was later lowered to $1.25.

Kearny County experienced its first real surge in land seekers between 1885 and 1888. When settlers arrived here, they found it drastically different from the ‘civilized’ areas they were accustomed to. Survival generally took the physical efforts of every member of a family, and only the most resilient souls succeeded in making their “home sweet home” on the Kansas plains.

As lumber was not readily available, resourceful pioneers turned to the earth to build their homes. Dug-outs were made by digging into a dirt bank, and sod houses were built from the abundant supply of thickly rooted prairie grass. Adobe bricks made of a mixture of mud, sand, clay, and straw or grass were also used. Some settlers were fortunate to have access to limestone to build their abodes, but many “settled” for tents, boxcars, small shacks or shanties.

The late Dave Grusing recalled moving to Kansas in September of 1908 with his parents, John and Anna. “We arrived about midnight in Leoti. Put our dogs and our baggage in the depot, then walked to the Jones Hotel about in the middle of Leoti. Herman and Grace and I walked. Dad carried Helen, and Mom carried Martha. We kids were barefooted and no sidewalks, just a plain path with plenty of stickers.”

The next morning after breakfast, Dave and his father walked downtown and “looked all around and saw nothing but open country. I asked Dad where the town is. Dad said, “You are in it now.” All I knew about a town was Salem (Oregon) and didn’t know what a small town like Leoti was like.”

The family’s first home in Kansas was a two-room sod house that belonged to a man who was away herding sheep. They were told they could stay there until he returned.

“Our new life on the prairie was exciting. The pasture north of this sod house had quite a lot of cow chips so Mom, Herman and I would pick a batch every day. Mom would bake the best of bread.” John Grusing purchased a cow for milk and butter. He also bought a shot gun. “He would shoot rabbits and we would eat them. Mother could make the best brown rabbit gravy to put on our bread.”

Then a man by the name of Krohm told Dave’s father that he was going to relinquish his homestead in the extreme northern part of Kearny County, and John Grusing could file on it. The legal papers went through the Dodge City land office about two weeks later. Krohm sold his belongings to John for $1,200. This consisted of four horses, four cows and calves, three hogs, 40 chickens, a wagon, a spring wagon, harnesses and some farm machinery, a well with a hand pump on it, a two-room sod house, a sod hen house, and a pasture fence.

Twenty years after the land surge, some places in Kansas still hadn’t changed much. Dave wrote, “When we moved onto the homestead, it was about as bare as anything could be – no trees, only three hollyhocks close to the dugout and four cucumber vines.”

SOURCES: Kansas State Historical Society; A Case Study of Kearny County, Kansas in the Populist Era by Harold R. Smith; A Standard History of Kansas and Kansans by William E. Connelley; History of Kearny County Vols. I & II; Hartland Herald and Advocate archives; Wikipedia; Center on Education Policy and Museum archives.