Images of a gun-slinging, rough-riding bandit generally come to mind when hearing the name “Jesse James,” but Kearny County’s Jessee was a kind neighbor and devoted father. The son of a Civil War doctor, he was married to his father’s younger half-sister according to Ancestry.com and Find a Grave records.

Jessee was born in 1860 to William “Doc Billy” and Phoebe (Perkins) James at Van Buren, Arkansas. At Fredonia, KS in 1881, he married Nancy Ann Priscilla James, the daughter of Jesse Ballard James and his second wife, Elizabeth Campbell. Jessee and Nancy’s first child, a daughter named Della, died two days after her birth in Bourbon County, Ks. Son Homer was born in Kingman County in 1884, and daughter Maybelle was born about 18 months later in Edwards County.

After hearing stories of how one could file on a homestead and tree claim, prove up, and gain ownership to several acres of land Out West, the James family decided to try their luck at a new location. In early March of 1886, they loaded their belongings into, on and around the sides of their prairie schooner, and Jessee, Nancy, Homer and baby Maybelle made their way to the north flats of Kearny County. They settled on the southwest quarter section of 12-22-36 with their two mules, two cows, a calf that was born on the journey west, 12 pigeons and their shepherd dog, Tige. The wagon was unloaded, and the wagon box with its bows and cover was set on the ground to serve as a hut for the family to stay in until a small home could be built. Instead of being covered with grass, the prairie was burned off black, supposedly by cattlemen trying to dissuade settlers. One of the first tasks at hands, besides building a dwelling, was to dig a well.

Sons Thurlow and Roscoe were added to the family in 1887 and 1890, respectively. Then, in 1893, the family moved to Jessee’s tree claim on the northeast quarter section of 4-22-36 so that the children could attend Columbian (later Columbia) School. Not yet five years old, Thurlow died in 1902 and baby Sula was born four months later. Water was hard to come by on the flats, and pioneer life was riddled with trials. The James’s saw many of their neighbors leave the area, but they pressed on. Jessee provided for his family by raising stock and farming. He also did occasional teamwork for neighbors who didn’t have the means to come to town and pick up necessities for themselves. Jessee served on the District 7 school board for 11 years and was serving on the Hibbard Township board at the time of his death in February of 1904. He had come to Lakin a few days earlier to secure necessary supplies for two of his children who were seriously ill, caught a cold and died of pneumonia at the family home.

After Jessee’s death, Nancy James homesteaded the northeast quarter section of 9-22-36. In 1905, she moved with her children to this land where the family could have an abundance of water without having to haul it. Nancy never remarried and died in 1946.

Homer and Maybelle filed on nearby homesteads when they reached the eligible age. Homer married Stella Hutton in 1910, and during 1911 and 1912, he worked in Wyoming as a cowboy on the TE Ranch which belonged to Buffalo Bill Cody. Later the family moved to New Mexico and then to Colorado where Homer succumbed to the Spanish flu in 1918. Stella returned to Lakin with the couple’s two children, Gaylord and Della (later Mrs. Glenn Anschutz). Two-year-old daughter Lena had died in 1914.

Roscoe James married Frances Wilkinson in 1910, and they lived for a time at Winfield, Kansas before moving to Colorado in 1923. The couple had 12 children, two of whom died in infancy. A retired carpenter, Roscoe was living at Pueblo when he died in 1963.

Maybelle became a teacher and lived for many years on her homestead just three miles west of her childhood home in Hibbard Township. She was married to Rudolph Gropp in 1911, and they moved into Lakin just a few years prior to Rudy’s death in 1969. Maybelle remained in Lakin until the mid-1980s when she went to live with her daughter, Elizabeth, in West Fork, Arkansas. Maybelle died in 1989 at the age of 103. She and Rudy’s son, Jesse Samuel, was living in California at the time of his mother’s death.

Sula James, also a teacher, married Arthur Mace of Wichita County in 1928. They started a sheep operation and moved in 1952 to Colorado where the water supply was better. After Arthur’s death in 1970, Sula returned to Lakin and made her home with Maybelle in a modest bungalow on Hamilton Street. She lived there until entering High Plains Retirement Village in 1990 and died at the age of 88 in 1991. Sula and Arthur’s only child, a daughter by the name of Nancy Ellen, died in infancy.

The story of Jessee James and his family is not unlike those of the other pioneers who ventured west and lived lives of hard work, courage, tribulation, and perseverance. None of Jessee’s descendants remain in Kearny County; nonetheless, the family is important to our history. Maybelle and her husband were charter members of the Kearny County Historical Society, and Maybelle recorded and shared a great deal of local history with the society. The Columbia Schoolhouse on Museum grounds was a gift from her to our entire community.

To know Maybelle and Sula was a gift in itself. As a little girl who lived just two doors away, this writer spent many a Saturday morning at their home hearing stories of their life on the Kansas plains and songs of old while watching the sisters tat, bead, crochet and more. They were fascinating, kind and joyful women who helped fuel the love of local history that courses through my veins.

SOURCES: History of Kearny County Vol. 1; Diggin’ Up Bones by Betty Barnes; Find a Grave; Ancestry.com; Museum archives and archives of the Lakin Independent and Advocate.

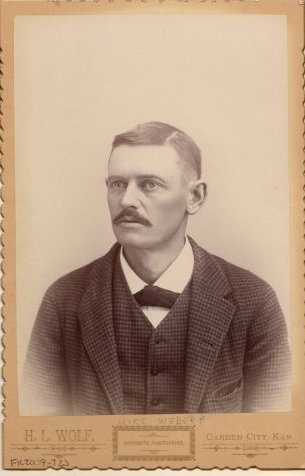

Mike Weber had a serious and somber demeanor and was not known to smile much. Yet, the brother-in-law of Lakin’s founding father was one of the most esteemed citizens in Kearny County. Michael A. Weber was born in Pennsylvania in 1856. He came west to Kansas in June of 1885, settling on a claim near Lakin. In 1895, he married Jennie Farrell at the home of Jennie’s older sister and husband, Mary and John O’Loughlin.

Mike Weber had a serious and somber demeanor and was not known to smile much. Yet, the brother-in-law of Lakin’s founding father was one of the most esteemed citizens in Kearny County. Michael A. Weber was born in Pennsylvania in 1856. He came west to Kansas in June of 1885, settling on a claim near Lakin. In 1895, he married Jennie Farrell at the home of Jennie’s older sister and husband, Mary and John O’Loughlin.