Chouteau’s Island was the site of a number of skirmishes, and it was one skirmish in particular that earned the island its name. In the spring of 1816, Auguste P. Chouteau and his hunting party were returning from the upper Arkansas in Colorado with a winter’s catch of furs when they were attacked by a band of 200 Pawnee Indians. They retreated to the island where the grove of cottonwood trees, thick clumps of willows and a heavy growth of tall grass provided excellent coverage. Despite being considerably outmanned, Chouteau’s party successfully fought off their attackers. One man was lost and three others wounded.

In 1828, more than $10,000 of silver was buried at Chouteau’s Island by a group of traders known as the Milton Bryan Party. The group was on the return trip from Santa Fe, and among Bryan’s party was a man by the name of William Young Witt. Witt, a third cousin to the grandmother of B.C. Nash, a lifetime Lakin resident, kept a diary of the journey. One morning after arriving at the Upper Cimarron Springs, Bryan’s party was awakened just before dawn.

“The whole earth seemed to resound with the most horrible noises that ever greeted human ears; every blade of grass appeared to re-echo the horrid din,” Witt wrote. “In a few moments every man was at his post, rifle in hand, ready for any emergency, and almost immediately a large band of Indians made their appearance, riding within rifle-shot of the wagon. A continuous battle raged for several hours.”

After successfully stampeding all the horses and mules, the Indians retreated. Hitt was wounded six times. (According to Bryan’s account and Hitt’s son’s account, Hitt was wounded 16 times.) The next morning, some of the men took off in hopes to find the lost stock. Hitt was on his way back to camp when he was overtaken by Indians, but some of his traveling companions arrived in time to save him. Unable to secure any of their stock, the entourage left by foot in the morning with each man shouldering a rifle and a proportion of provisions. After eight days travel, they had less than 100 pounds of flour left and had been unsuccessful in finding any game.

Hitt recalled, “For two weeks the allowance of flour to each individual was but a spoonful, stirred in water and taken three times a day.” Adding to their futility was a scarcity of water. In desperation, the troupe was once compelled to suck the moist clay from a buffalo wallow.

As soon as a convenient camping ground was found, the men made shelter and left the weakest of their party while some of the strongest hunted. Successful at last in killing some small game and buffalo, they used buffalo chips to fuel a fire. After a few day’s rest, the men began again to march homeward, but their money had become a greater burden than they could bare. They decided to bury it at the first good place they came upon.

“We came to an island in the river to which we waded, and there, between two large trees, dug a hole and deposited our treasure…This task finished, with much lighter burdens, but more anxious than ever, we again took up our march eastwardly.”

Traveling for over two weeks by foot, the men were exhausted; some scarcely able to move. They divided company, the weaker ones to proceed by easier stages. When the stronger ones arrived at the settlement, they sent a party with horses to bring in their comrades who were seemingly nothing but human skeletons wrapped in rags, but “all got safely to their homes.”

The following year, the traders returned to Chouteau’s Island; however, Hitt is not mentioned as being among the group of men. Their party was accompanied by Major Bennett Riley and his men, the first military escort on the Trail. The silver was retrieved, and the trading party continued their trek to Santa Fe with their goods. South of the river was Mexican territory, and the American troops could go no farther. The traders began their journey down Bear Creek pass and were attacked by a band of Indians upon entering the sandhills. Nine of the men, riding at full speed, returned to the soldiers with the dreadful news. The troops disregarded their orders and made a hurried march across the river to defend the caravan. One trader, Samuel Lamme, lost his life in the assault, and his tortured and mutilated body was laid to rest at the edge of the hills not far from the Trail. Riley and his troops accompanied the traders for two more days and then reluctantly returned to Chouteau’s Island where they camped for three months awaiting the caravan’s return.

Between 1865 and 1870, a caravan of traders was attacked by Indians in the valley between Chouteau’s Island and Indian Mound. Word reached Fort Garland of the attack, and soldiers were sent to the scene. By the time they reached the area, the Indians had fled and the traders were all dead. The soldiers buried them and returned to Fort Garland. Legend has it that the burial ground was visible for many years as the grass there was much greener.

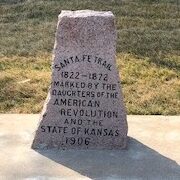

In 1941, Kansas was celebrating the 400th anniversary of the coming of Coronado to Quivira, the first white man to visit Kansas. The occasion was observed by placing historical markers all over the state. Kearny County held a Pioneer Day celebration that July, and a crowd of more than 1,000 witnessed one of the largest parades in Lakin where 10-gallon hats, cattlemen’s garb, pioneer costumes, horse riders and buckboards were abundant. Following a program at the court house, participants drove a mile west of Lakin on US 50 for more speeches, music, celebrating and the unveiling of the Chouteau Island marker. Although the original sign is long gone, a sign commemorating Chouteau’s Island can still be found just west of Lakin at the roadside park beside the golf course.

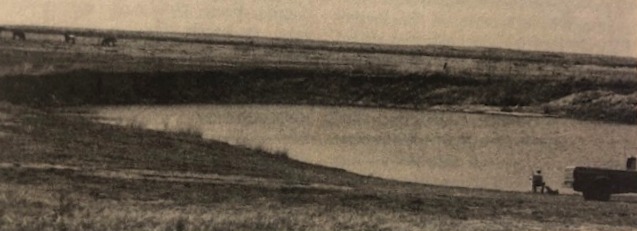

Photos from the 1941 Chouteau’s Island marker reveal. The island once rose lush and green in the middle of the Arkansas River, its disappearance blamed on natural forces, flood control measures and the use of the Arkansas for irrigation.

SOURCES: “William Y. Hitt Santa Fe Trail Memoires,” “The Old Santa Fe Trail” by Colonel Henry Inman, “Commerce of the Prairies” by Josiah Gregg, “The Flight of Time” by Milton E. Bryan, “Kansas Before 1854: A Revised Annals” compiled by Louis Barry, “Chronicle of Bennett C. Riley” by Leo E. Oliva; History of Kearny County Vol. 1, & ancestry.com. Special thanks to Meg Nash Spellman.