During the settlement of the west, the survival of a town often hinged upon its ability to win the county seat. Rival towns resorted to fraud, bribery and even deadly violence to secure the prize, and Kearny County was not without its share of misconduct. With Lakin being the oldest settlement in the county, one might think that Lakin’s designation as county seat was a done deal, but that was far from the truth.

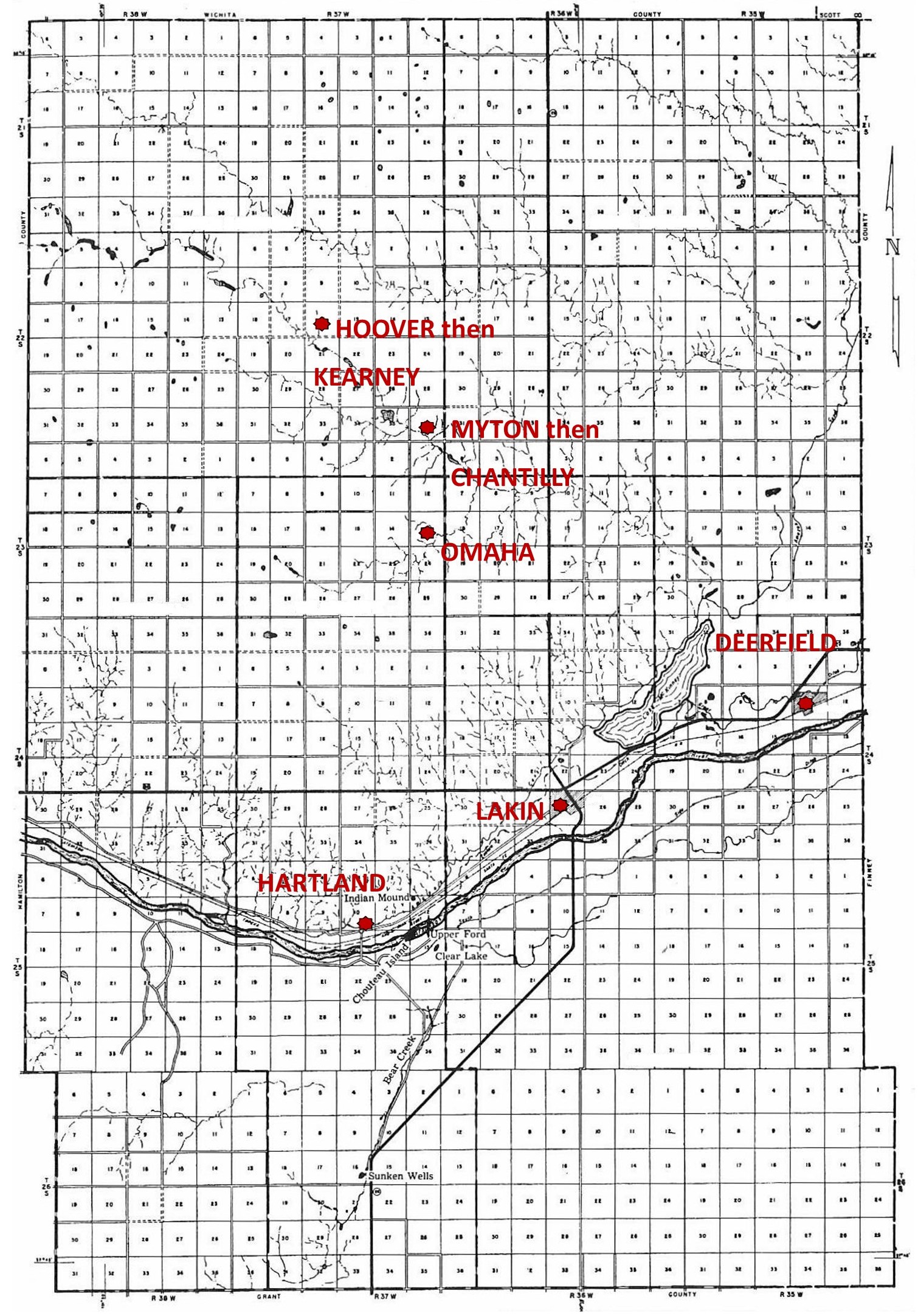

In early summer 1885, a Hutchinson-organized town company bought a section of land from the railroad at the station of Hartland about seven miles west of Lakin. The Hartland town company advertised extensively using alluring and glamorous descriptions of the area to draw speculators, land seekers, business men and laborers to the “Rose of the Valley.” Located near the north end of Bear Creek, a natural dry creek that cut through the sandhills to the Arkansas River Valley, Hartland was at the right place at the right time. In April of 1886, the Bank of Hartland was established with a capital of $50,000. The following month, Hartland reportedly had over 125 residences and business houses including six lumber and hardware stores, seven general stores and groceries, four land and real estate agencies, two hotels, a livery, blacksmith, harness maker, and a furniture store. Hartland was soon vying for county seat, but the booming community was not Lakin’s only rival.

North Kearney represented the largest territory, and from 1886 to 1888, several short-lived northern towns sought the county seat. The first was Hoover, established 18 miles north of Hartland in April of 1886. Named for Hartland businessman, G.M. Hoover, this town was an offspring of Hartland enterprise and the halfway point on the stageline from Hartland to Leoti. By August, the town name had been changed to Kearney. Although the townsite did have a post office for a number of years, in reality Kearney was little more than a few buildings.

By December of 1886, the townsite of Myton was being laid out about 10 miles north and three miles west of Lakin. In March of 1887, Carolina Virginia Pierce had 40 acres laid out in town lots at Myton, and the following month, a committee accepted Mrs. Pierce’s offer of 80 acres as the place to locate the proposed county seat of Kearney County. Myton was then renamed Chantilly. (County namesake Philip Kearny died in the Battle of Chantilly during the Civil War.) The largest of the “flats” towns, Chantilly boasted a large hotel, two general stores, a restaurant, a livery stable, blacksmith shop, post office, newspaper, and school at the height of its existence.

Kansas Governor John Martin appointed a census taker in 1887 to enumerate the inhabitants of the county, but this was not an easy task. Each legal voter was entitled to sign the petition for naming the county seat in one of the rival towns. The folks at Chantilly charged that Lakin had shipped in 200 to 300 transient voters who were distributed all over the county, and Hartland openly offered town lots in exchange for signatures. Promoters representing each of the towns did everything they could to have as many as possible enumerated who would be on their side and leave those uncounted who were opposed. The grand total number of signers who affixed their names to the petitions was 2,891 although it was doubtful if there were 500 people in the whole county. The northern territory consolidated as Kearney withdrew, throwing its strength to Chantilly which was far in the lead until Lakin’s petition came in with a list of names alleged to be padded. On March 27, 1888, Gov. Martin issued a proclamation designating Kearney County as a permanent county and Lakin as temporary county seat until a legal election could be held. Gov. Martin appointed temporary county officers: three county commissioners, a county clerk, and a sheriff. Chantilly’s charges of fraud went to the Shawnee County court, but Lakin prevailed. The following year, the state legislature dropped the second “e” from “Kearney” to reflect the proper spelling of General Kearny’s name.

Almost immediately, Lakin’s temporary officers committed “questionable” acts by issuing fraudulent warrants and misspending county funds. When citizens elected county officers in November of 1888, one of the first orders of business was an examination of warrant records, stubs and vouchers by the newly elected county attorney. Considerable examples of misconduct and excessive and fraudulent expenditures were found – thousands of dollars worth of bonds had been issued, sold to the unsuspecting and then pocketed or spent largely to retain Lakin as the permanent county seat.

There had been so much fraud and legal expense that the burden was more than Chantilly supporters could shoulder. They gave way to Omaha which had been organized by the Omaha Town Company, a group of promoters who were willing to take over the cause of North Kearney. Omaha made a last bid for the county seat. Lots in Chantilly were exchanged for lots in Omaha and the buildings in Chantilly were put on rollers and moved roughly three miles south to Omaha. By the time the county seat election rolled around on Feb. 19, 1889, most of those remaining in North Kearny cast their lot with Hartland. The late D.H. Browne said one of the most dramatic events in his life was counting the votes. Each county seat contestant had the privilege of sending someone to see that the votes were properly counted. Undersheriff Barney O’Connor was Lakin’s representative and stood over the election judges with six-shooter in hand. Mr. Browne said he never expected to get out of the building without someone being killed.

Hartland was victorious, and Lakin felt robbed. O’Connor served an injunction on county commissioners restraining them from canvassing the vote and also restraining all county officers from moving their offices to Hartland. Several cowboys came to Lakin, swiped the county books, and galloped away to Hartland. O’Connor and Tommy Morgan, who had come to Lakin years earlier in the employ of the Santa Fe, strapped on guns and went to Hartland to get the books back. Lakin hired guards to watch the courthouse day and night. The case went to court, and Lakin was ordered to give up the records. Despite Lakin’s claims of fraud, the Kansas Supreme Court officially ruled Hartland as the victor.

Not familiar with western conditions, many of the homesteaders who had come from the east had left by 1894. Hartland was slipping and no longer had a newspaper, but from all appearances in the Lakin papers, the two communities were co-existing peaceably. Then the Hartland court house caught fire January 17, 1894. Although there was speculation that the fire had been set, no one was ever charged with the crime even after county commissioners offered a $1,000 reward. A special election was held in June to remove the county seat to Lakin. Unlike earlier skirmishes, the election passed off quietly. Lakin was, at last, the county seat of Kearny County.

SOURCES: Cyclopedia of Kansas History; Kearny County Populist Era by Harold Smith; May 1, 1886, May 15, 1886 and Sept. 4, 1886 and Feb. 2,1889 Hartland Herald; March 12 and Apr. 2, 1887 Lakin Pioneer Democrat; Jan. 1 and April 9, 1887 Kearney Koyote; Apr. 28, 1888 and Feb. 2, 1889 Kearny County Coyote; May 19, 1886 Garden City Sentinel; Dec. 25, 1886 and Dec. 14, 1889 Advocate; Aug. 27, 1948 Lakin Independent; History of Kearny County, Kansas Vol. 1 & 2; Kansas State Historical Society, and museum archives