The survival of hometown newspapers is uncertain in this digital age. According to the University of North Carolina’s Hussman School of Journalism and Media, the United States lost one-fourth of its newspapers between 2004 and 2019. This included 70 dailies and more than 2,000 weeklies or nondaily papers. Eighteen of those papers were in Kansas.

Too many people won’t realize the value of their local paper until the paper no longer exists. For some, the loss won’t be felt until years later when they are trying to research family, community and other historical events. Newspaper editors and reporters have been the prime, sometimes sole, source of credible and comprehensive news and information in their communities. This is especially true for residents in small towns like Lakin. For researching Kearny County, there is no better place than the archives of our local papers.

The Lakin Eagle was the first paper to be printed in Lakin with the inaugural issue released in May of 1879 and the last issue on October 10 of that year. The four-column, four-page tabloid had three different editors during its short life.

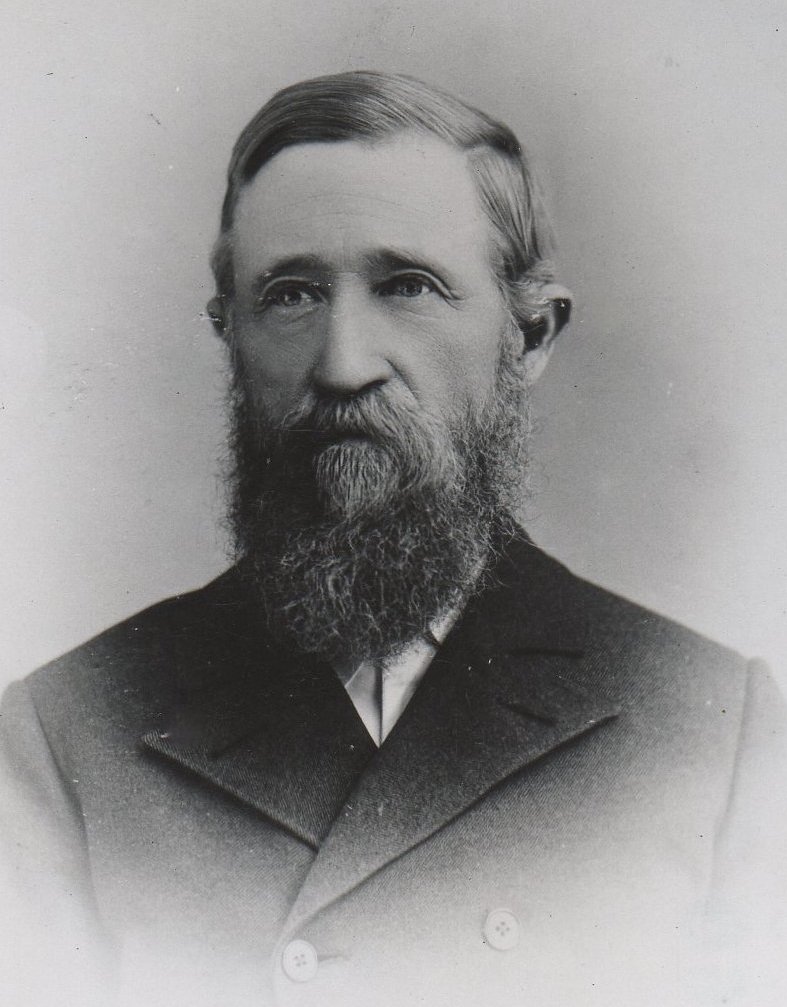

The Lakin Herald was a full-sized publication that ran monthly from June to December of 1881 when it began publishing weekly. This was a remarkable feat at that time because the linotype had not yet been invented, and printing was a tedious task with each letter of each word having to be set by hand. Editor Joseph Dillon was an excellent story teller but admittedly could not set type, a task left to his daughter Maria. A yearly subscription to the Herald sold for $1.50. The last issue archived in Kansas State Historical Society files is dated June 27, 1884.

From 1885-1890, A.B. Boylan published Lakin Pioneer Democrat. The full-size weekly paper had four pages. Pages 1 and 4 were ready print, meaning they came to Boylan already printed eliminating a good deal of the typesetting. Those pages contained news and advertisements from across the state and nation. Local news and advertisements were printed on the inside pages. This was a common practice at that time.

The lone issue of The Lakin Union was published by H.S. Gregory on March 28, 1895. The following week, Gregory announced that he had purchased the subscription list and franchise of the Kearny County Advocate. “Owing to a legal complication we continue the name of the ADVOCATE and drop that of the LAKIN UNION.”

F.R. French published The Lakin Index, a full-size weekly paper, from 1890 to 1898. He then went on to publish The Lakin Investigator for a year. The Investigator had several editors and publishers during it existence, one of which was Harry Tate. The last issue of the paper ran on Jan. 6, 1911. The paper was then merged with The Kearny County Advocate, the second-longest running paper in Kearny County.

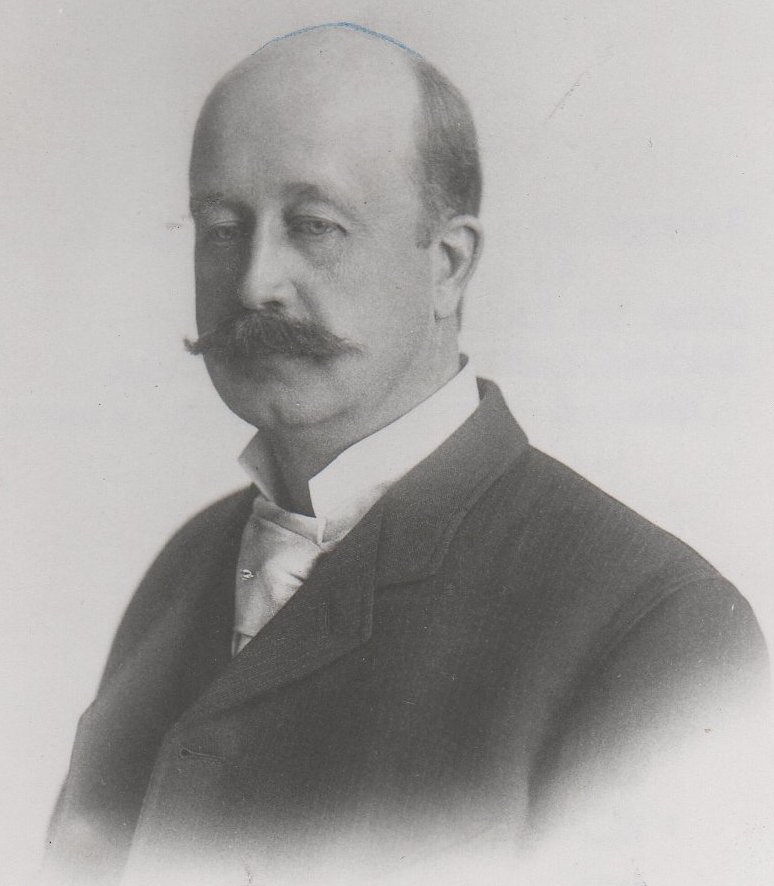

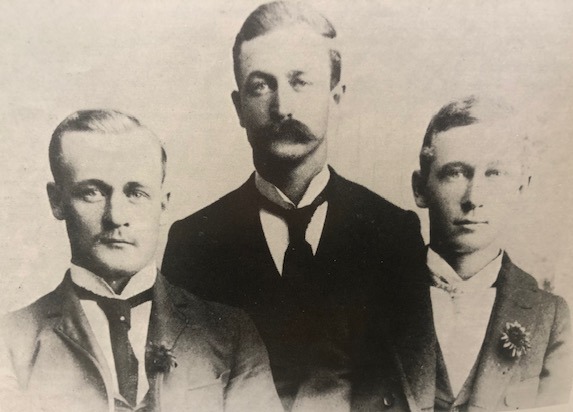

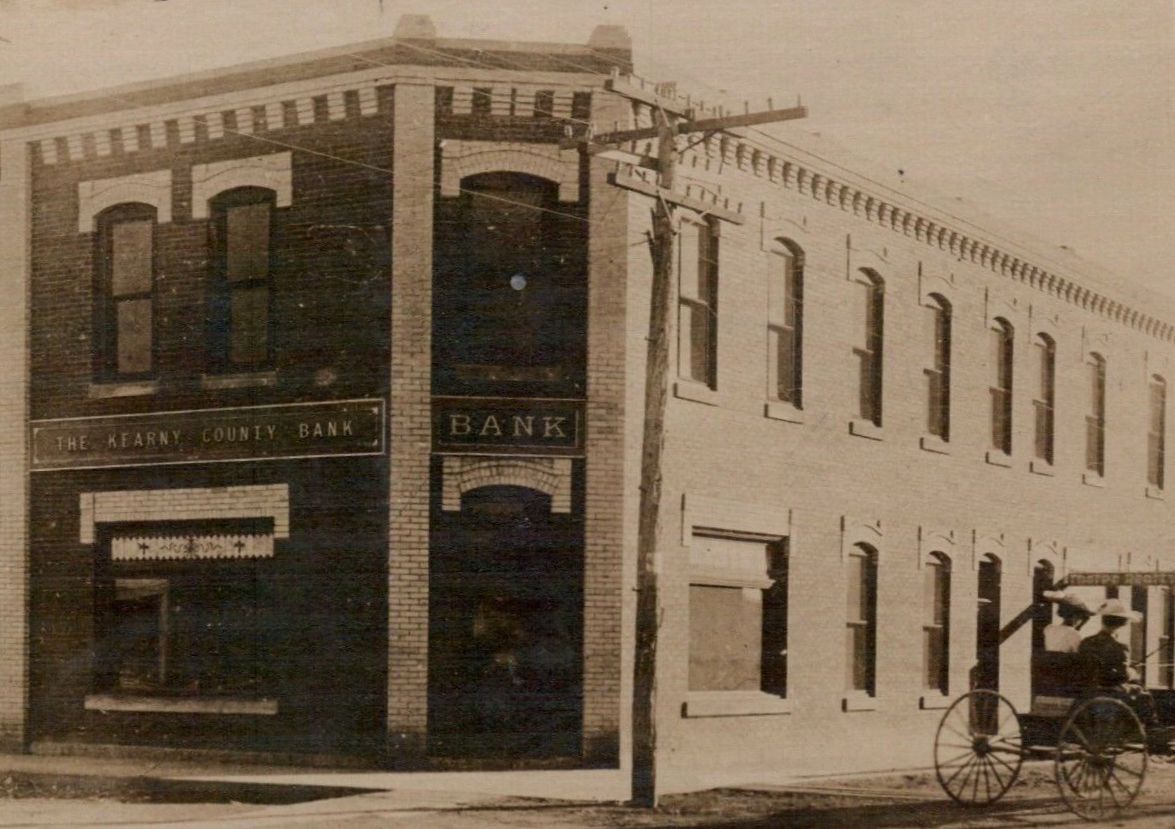

The first issue of The Kearney County Advocate was printed on May 23, 1885. Beginning with the May 29, 1890 issue, the spelling was changed to Kearny County Advocate. After merging with The Investigator in 1911, the paper ran eight issues under the name of The Kearny County Advocate and The Lakin Investigator. The name was then changed back to Kearny County Advocate until January 1918 when it changed to simply The Advocate. The weekly paper went through three editors in its first year: Charles S. Hughes, Tune Bentley and F.R. French. That changeover was just a glimpse as to the many times the paper would change hands during its existence. The brothers Menn (R. Thorpe and Don) served as the paper’s last editor and publisher, respectively. After selling the paper, the hometown boys continued in the print media field with Thorpe working in several capacities at the Kansas City Star and Don joining the production department of the McCall Corporation which printed McCall’s Magazine, Reader’s Digest, Newsweek and more.

The Lakin Independent was launched July 10, 1914 by M.B. Royer and was purchased by local girl Grace Hamblen in 1919. Edward Stullken bought the paper in 1922, and in 1937, he bought out The Advocate and merged it with the Independent. When Stullken retired from active newspaper service in 1946, his son Leslie took charge for a year before leasing the paper to Monte and Gloria Canfield in 1947. The Canfields purchased the Independent in 1953. Monte was one of the best in the business with an innate writing ability, wit, and a true sense of community. He passed in 2003, and long-time Independent employee Kathy McVey and her husband, Joe, bought the paper in 2006.

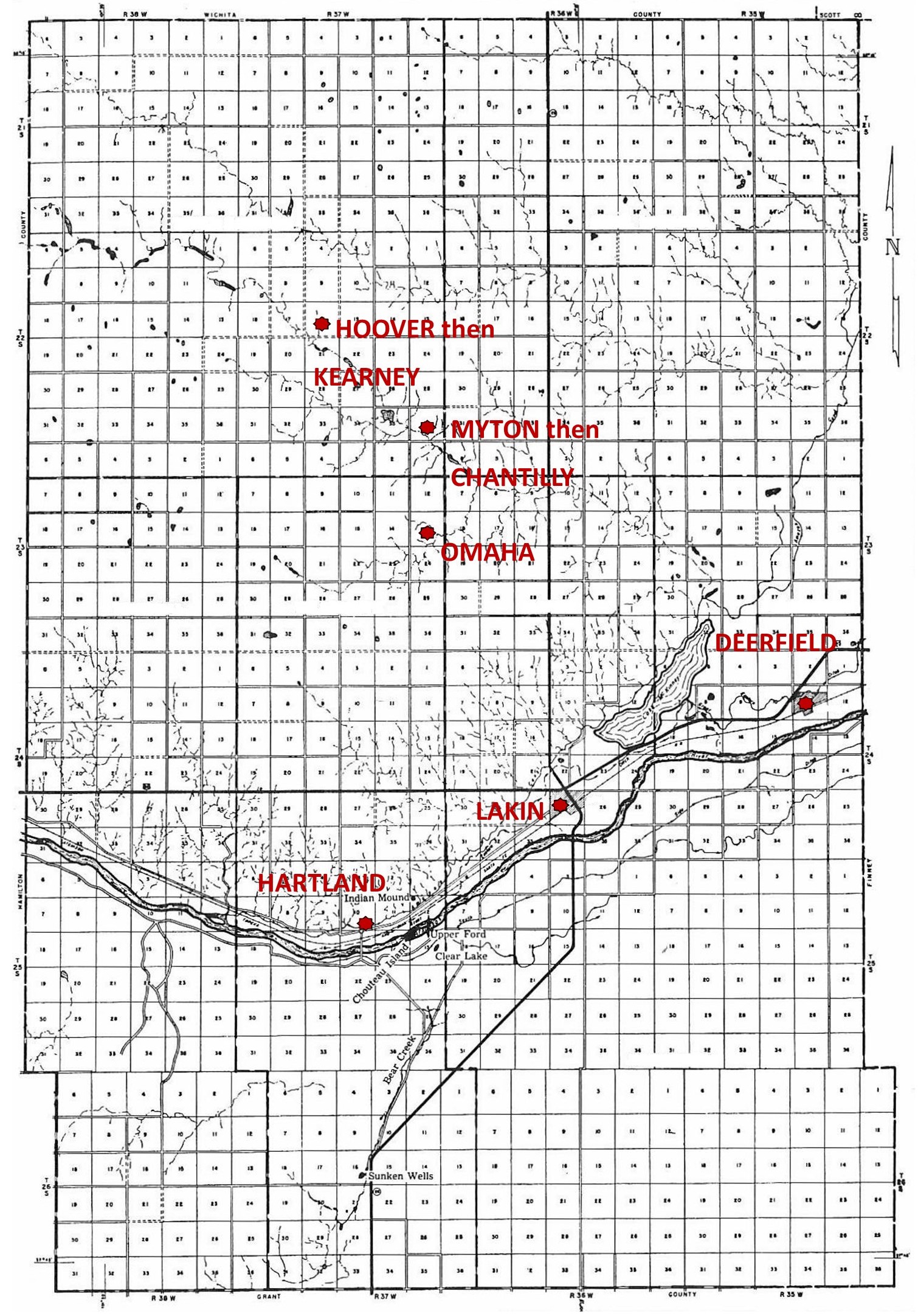

Deerfield, Hartland and the North Flats also had their share of newspapers. The last of those papers to survive was Deerfield’s Arkansas Valley Builder which ceased operation nearly a century ago.

The value of our current and past newspapers cannot be overstated. Almost every day museum staff use the archives to fulfill a research request, to write an article, add information to museum files, or to confirm or correct previously published information. Clippings are taken from the current Independents as well and filed for future reference. Where would be without our local paper? Hopefully this community will never have to find out.

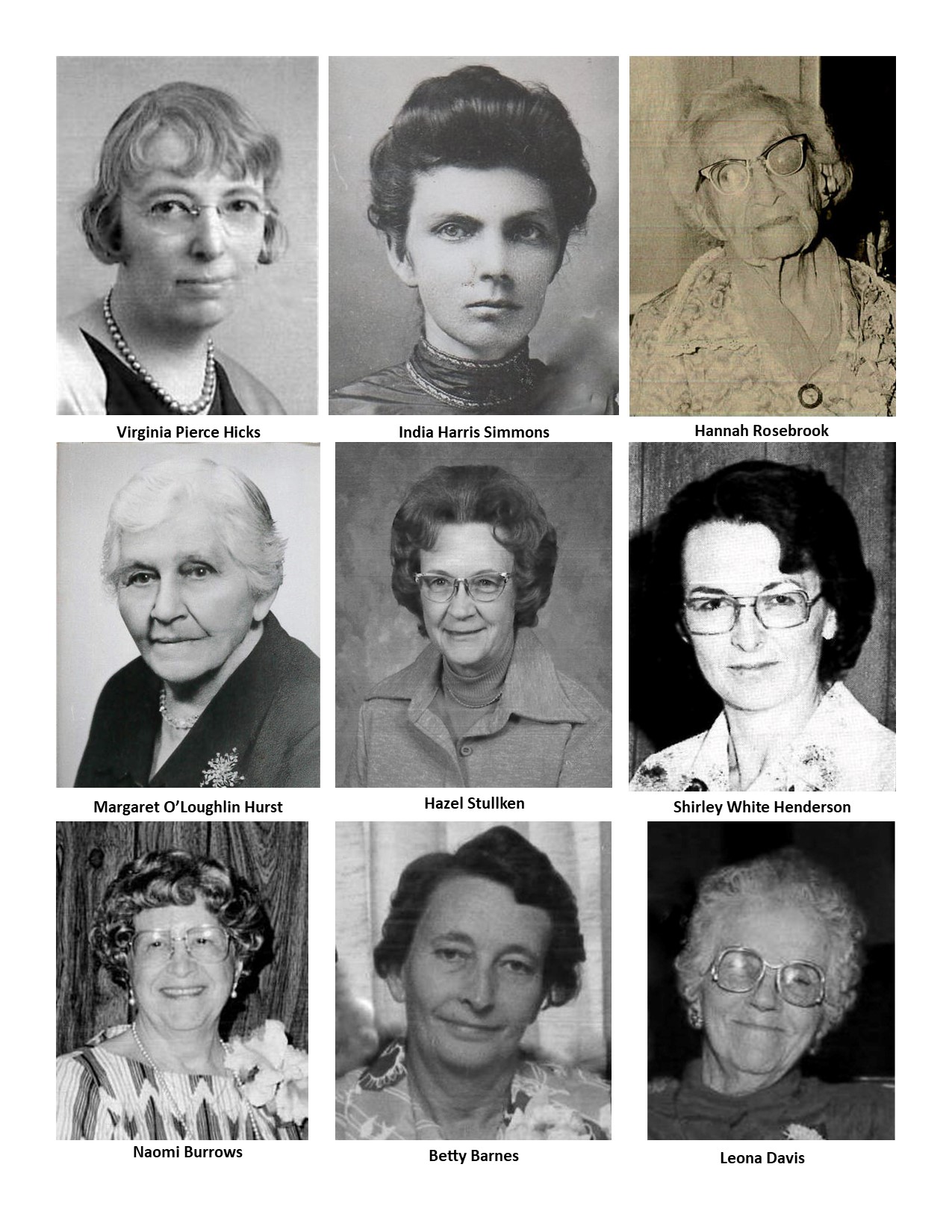

SOURCES: Much of the information in this article was researched for Volume I of the History of Kearny County by the late Hazel Stullken, daughter-in-law of Ed Stullken and an Independent employee for over 40 years; museum and newspaper archives; High Plains Public Radio; and USnewsdeserts.com.