Over a two-week period in November of 1900, the Revs. E.M. Carr and R.H. Tanksley conducted a series of meetings in Kearny County in the interest of the Christian Church. Carr, of Dodge City, was the president of the Eighth District, and Tanksley had recently been appointed to serve Syracuse and Lakin. The Nov. 29, 1900 Advocate reported, “Rev. Carr immersed four converts to the Christian church, in the Day pond,” while “Rev. Tanksley immersed seven converts of the Christian faith in Fulmer’s pond in Southside township.” This was the beginning of Lakin’s First Christian Church. In January, the Kansas Messenger reported that 14 had been baptized in Kearny County during this time. Among the charter members were Mr. and Mrs. Harmon Tipton, Mary Tipton, Hanna Neely, Lottie Neely, Mr. and Mrs. H.H. Cochran, and Mr. and Mrs. Nathan Fulmer.

The members met in the Presbyterian Church at first, but later the congregation began meeting in the courtroom of the old courthouse that was located on the southeast corner of Main and Waterman. In late June of 1907, the congregation assembled at Mr. Tipton’s home and elected him, Fulmer, Cochran, Thomas Gibson, Charles Bastion and N.C. Walls to serve on a building committee for a new church with Rev. J.R. Robertson serving as chairman. A lot at the corner of Buffalo Street and Lincoln Avenue was purchased from A.G. Campbell for $190, and excavation work for the foundation, heater and coal bin were nearly finished by mid-September with most of the labor being performed by Tipton, Cochran and Fulmer. The cement block walls started going up in November. The roof was in place and the church fully enclosed by mid-March. The edifice of the church was designed in a square to “enable the audience generally to get nearer to the preacher than in a church of ordinary shape.”

Dedication services took place on June 14, 1908. The church had a “splendid seating capacity” but was filled to the doors to hear the sermon of Dr. W.L. Harris of Washington, D.C. Over $1,100 was raised in less than half an hour, and the church was dedicated clear of debt. There were no services at the other local churches that day as Presbyterian, Methodist and Baptist ministers were present and took part in the services. “The Christian people are to be commended and congratulated on their liberality in building this beautiful church home,” praised the Lakin Investigator.

In 1909, the Advocate reported that the Christian Church had put in “a baptistry just back of their meeting house.” The baptistry and classrooms were added inside the church in the late 1940s. In February 1951, Brother and Sister Robert E. Larson came. The church had been working on a parsonage, but it was only partly completed. Thanks to the willing and able hands of Brother Larson, the five-room, one-bathroom parsonage was completed. New stained glass windows were also put in the church and floors were refinished. Over the years, other remodeling projects were completed such as the installation of a bathroom, a handicap ramp on the west side of the church and a paved parking lot to the south.

The church had many good ministers, but there were also times when a minister couldn’t be found, and the pulpit was filled with lay people or ministers from other denominations here in Lakin and Christian churches in nearby communities. The first minister after moving into the new church was Bro. C.F. Bastion. The church had 94 members and gained some during his pastorate. By 1931, the membership was 65, but many members left the community during the Dust Bowl and Great Depression. The members who were left were so nearly stranded financially that it seemed it would be necessary to close the doors, but the few faithful ones still carried on.

The ups and downs in membership continued through the years, but no matter the size of the congregation, there were always enough dedicated members to keep the church going . . . until there wasn’t. In November 2014, the church, parsonage and other miscellaneous property were auctioned off due to declining membership. Serving the church as chairman, treasurer and secretary respectively at that time were Raymond Kitten, Cary Henderson and Curtis Young who worked unselfishly and tirelessly until the doors were closed. Two pews and the church bell were donated to the Kearny County Museum, and the church building now houses the congregation of IGLESIA APOSTOLES Y PROFETAS.

SOURCES: History of Kearny County Vols. I & II; museum archives; and archives of The Kansas Messenger, Dodge City Globe, Kearny County Advocate, Lakin Investigator, and Lakin Independent.

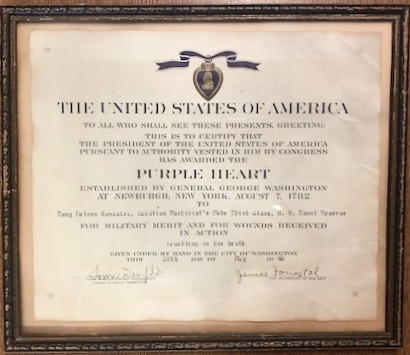

Tony was awarded the Air Medal for distinguishing himself by meritorious acts and demonstrating heroism while participating in flight operations, and in May of 1946, he was honored with the Purple Heart for military merit and for wounds received in action which resulted in his death. In 1950, Tony’s parents accepted his Distinguished Flying Cross medal in a ceremony at the Veterans Memorial Building. The honor was bestowed for Tony’s heroism and extraordinary achievement as an air-crewman in Patrol Bombing Squadron 101 during operations against enemy Japanese forces from June 1 to October 23, 1944. “Gonzalez rendered invaluable assistance to his pilot in carrying out hazardous long-range attacks against hostile planes, shipping and ground installation in the face of anti-aircraft fire and aerial opposition…Gonzales, by his skill and courageous devotion to duty throughout this period, upheld the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service. He gallantly gave his life for his country.”

Tony was awarded the Air Medal for distinguishing himself by meritorious acts and demonstrating heroism while participating in flight operations, and in May of 1946, he was honored with the Purple Heart for military merit and for wounds received in action which resulted in his death. In 1950, Tony’s parents accepted his Distinguished Flying Cross medal in a ceremony at the Veterans Memorial Building. The honor was bestowed for Tony’s heroism and extraordinary achievement as an air-crewman in Patrol Bombing Squadron 101 during operations against enemy Japanese forces from June 1 to October 23, 1944. “Gonzalez rendered invaluable assistance to his pilot in carrying out hazardous long-range attacks against hostile planes, shipping and ground installation in the face of anti-aircraft fire and aerial opposition…Gonzales, by his skill and courageous devotion to duty throughout this period, upheld the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service. He gallantly gave his life for his country.”