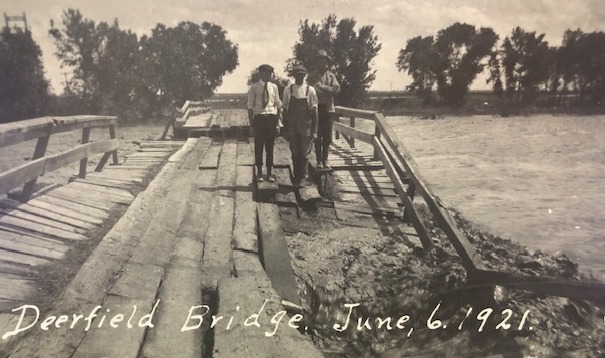

In March of 1925, the new bridge over the Arkansas at Deerfield opened to much fanfare. A parade was formed going out to the bridge where Commissioners George B. Martin and Thomas Williams took down the bars and the long procession passed over. After the bridge’s inspection, Rev. H. J. Karstensen of the Deerfield Lutheran Church gave a superlative speech suitable to the occasion. This was followed up by more speeches and then a free dinner at Deerfield’s theater. Over 500 meals were served, and the Kearny County Advocate reported that the crowd was one of the largest that Deerfield had experienced in a good many years.

According to the March 27, 1925 Lakin Independent, the bridge was 630 feet long and consisted of seven spans of 90 feet each. Twenty-five-foot piling was driven into the river bed as a foundation for the concrete pillars to rest upon. They reached the solid ground below the sand and cut off eight feet below the surface to prevent rotting. Steel strings with steel banisters were built to span the distance between the pillars upon which a concrete floor was laid. A one-lane structure with a width of only 16 feet, the bridge was considered wide for that period of time and was one of the most substantial structures across the Arkansas River in Kansas. Engineer R. B. Glass said the new bridge would hold up a Santa Fe train. The entire cost of the bridge, according to the paper, was $48,902.25.

In November of 1976, The Lakin Independent reported that the contract for a new bridge at Deerfield had been awarded to L & M Construction Company of Great Bend, Kansas, on a bid of $285,988. Load capacity of the old bridge had been limited to passenger vehicles and light trucks, and the Kearny County highway department constructed a temporary crossing in the river bed the previous year so that farm trucks and heavier industrial loads could cross the river.

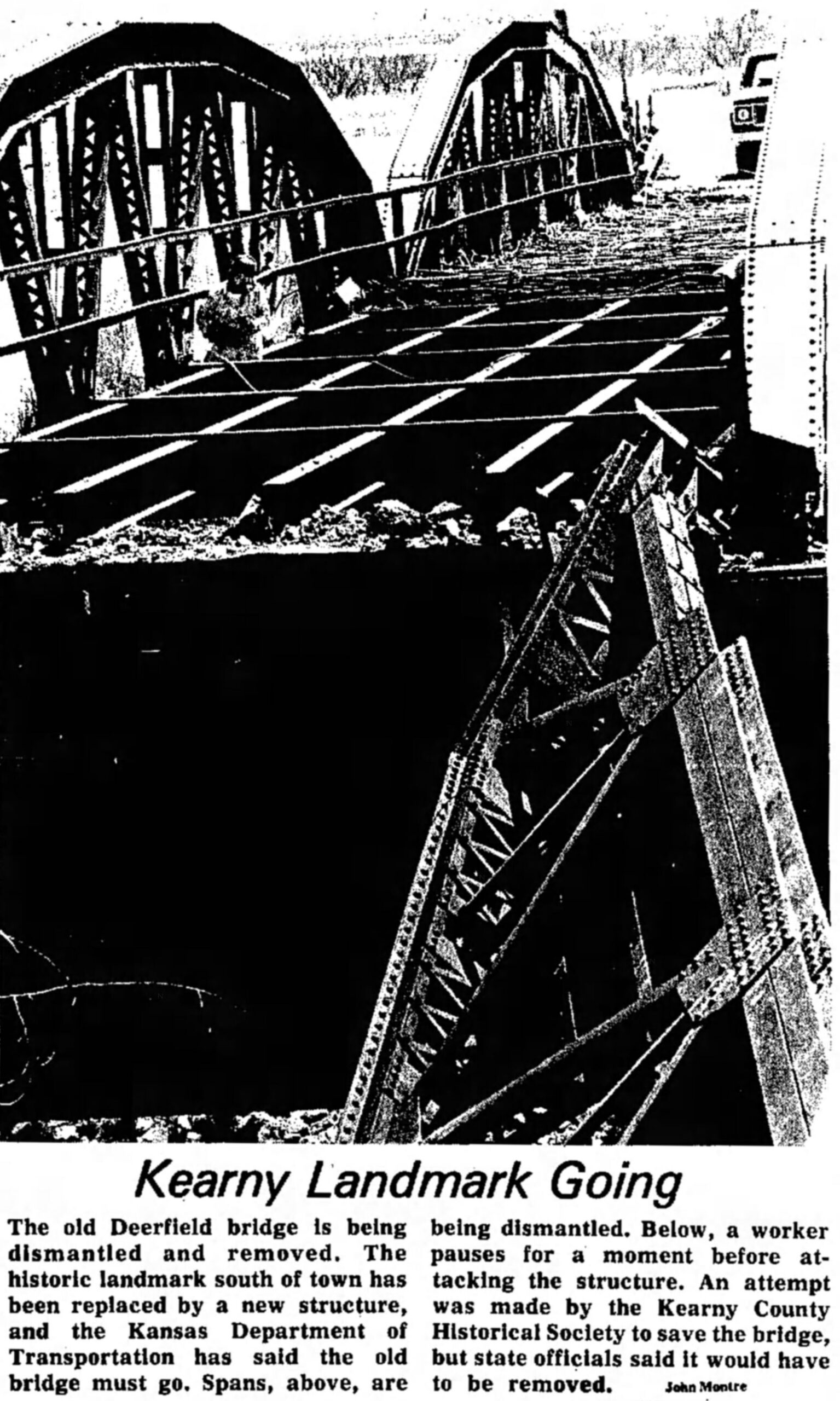

Former Kearny County Historical Society president Foster Eskelund wrote to O.D. Turner, Secretary of the Kansas Department of Transportation, in hopes that the old bridge would be deeded to the KCHS which would preserve the historical landmark, and a petition was circulated to this effect.

Eskelund received his answer in March of 1978 when Raymond E. Olson, engineer of secondary roads for the State of Kansas, replied to Foster’s request. Because the new bridge across the Arkansas River was constructed immediately adjacent to the old bridge with only about an eight-foot clearance between the two, and the spans between piers of the bridges were of different lengths, there was no line-up of the piers. “This has the effect of providing many obstacles in the river that tend to collect trash and trees which the Arkansas River is famous for during periods of flood. There is a good possibility that the piers of the old bridge will collect and build up debris until it deposits in the piers of the new bridge. We do not think this would be a good thing for the new facility,” wrote Olson. “It is the matter of debris that becomes the primary reason to remove the existing bridge.”

Although Olson said that the KCHS might be able to negotiate with the contractor to dismantle a span of the old bridge for assembly at another place, there is no evidence in the society’s records that this was ever done. Dismantling of the old bridge began in April of 1978.

SOURCES: Museum archives and archives of the Advocate, Independent and Garden City Telegram.

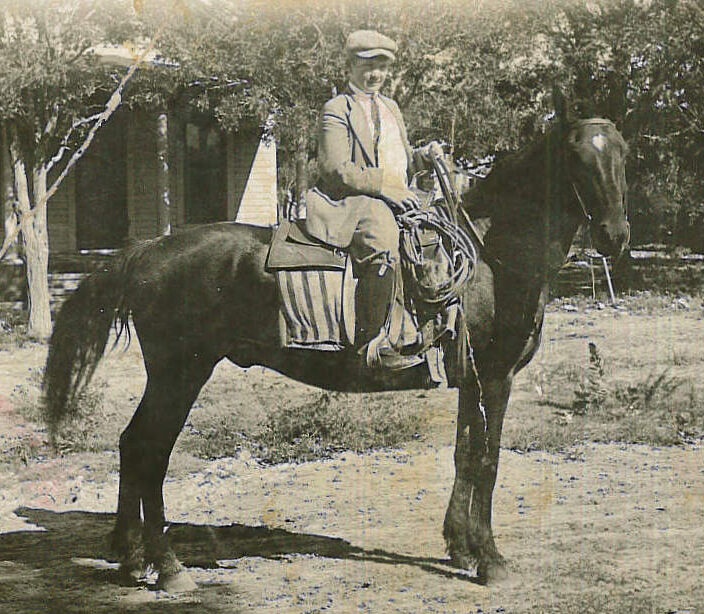

Tom O’Loughlin was a much-loved, good-natured friend to all. He always remembered those he met, always spoke to all of high and low degree, and was willing and ready to help in times of trouble. He was known for his Irish humor and often participated in community and school events including skits and fairs. He particularly enjoyed dances.

Tom O’Loughlin was a much-loved, good-natured friend to all. He always remembered those he met, always spoke to all of high and low degree, and was willing and ready to help in times of trouble. He was known for his Irish humor and often participated in community and school events including skits and fairs. He particularly enjoyed dances.