The Class of 1921 was the first to graduate from the new building which was surrounded by the beautiful school park. The much-loved grove of trees had been planted by A.W. Sudduth, a custodian of the 1886 building and was a popular place for community picnics and gatherings.

The Class of 1921 was the first to graduate from the new building which was surrounded by the beautiful school park. The much-loved grove of trees had been planted by A.W. Sudduth, a custodian of the 1886 building and was a popular place for community picnics and gatherings.

Summer break officially ended for Deerfield’s students yesterday when the U.S.D. 216 Spartans started back to school. In the early days of our county, school typically did not start until September and sometimes even later as children were often needed to help on their family’s farms. The first school for the children of the Deerfield community was a subscription school located a half mile east of town in the home of H. Charles and Belle Nicholls. According to their granddaughter, both Mr. and Mrs. Nicholls taught that school term of 1885-1886.

Mr. Nicholls was serving as the secretary pro. tem. of the District 3 school board in August of 1886 when the decision was made to build a school house in Deerfield. The area had experienced a large influx of settlers, and a frame building was erected that was large enough to be divided into two rooms when needed to accommodate all the children. The school opened in October of 1886 with Miss Sallie Eastham as the teacher. In March of 1911, voters approved bonds to build a new brick school house in Deerfield. The old school building was sold to the Baptists and moved two blocks south of the school grounds where it served as a church. Later the building was used as a first-grade classroom, then as an industrial arts class room for the high school, and finally as a community building and grange hall for the Deerfield and Pomona Granges.

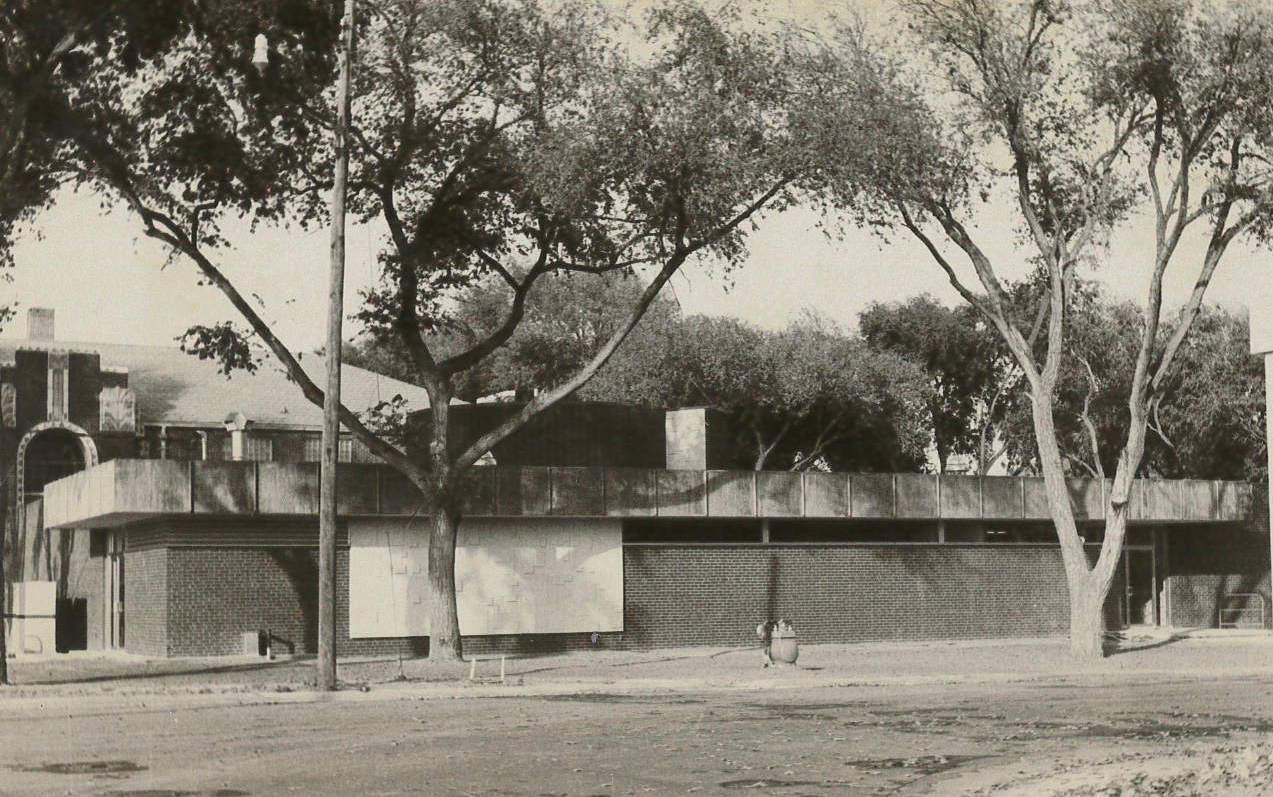

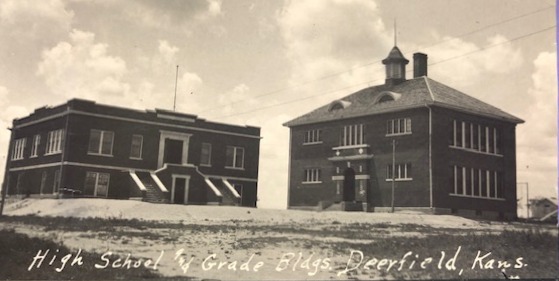

Deerfield’s first brick school house was constructed for an approximate cost of $12,000 and was available for the 1912-1913 school year. Although the building itself was very modern for that time, the school lacked the conveniences of running water, electricity and gas heat. The first heating system used was a coal furnace, and drinking water was provided by large water cans in each room with each student providing his or her own drinking cup. Part of the recess period was spent in refilling water cans. No lighting of any type was used. That school year a covered wagon drawn by a team of horses and driven by Bert White was used for Deerfield’s first organized mode of transportation for school children.

The school housed both grade and high schools with the high school faculty consisting of only one teacher, C. Edgar Funston, who taught Latin, algebra, English, ancient history, geometry, medieval and modern history to freshmen and sophomores. Funston also taught a full course of eighth grade subjects. His classes were conducted on the upper story while the two lower rooms were used for the primary grades. The following year, the high school classes were moved into the west room upstairs which had been partitioned to provide for a class room and to accommodate an additional teacher. By the end of the 1914-1915 school year, Deerfield had become a fully accredited three-year high school. The first graduating class in May of 1916 had three students.

The school term of 1915-1916 saw many improvements made to the school building. Among these was the addition of electricity and running water. Wells were drilled and equipped with automatic electric pumps, and pressure tanks were installed in the building. By the end of the 1919-1920 school year, Deerfield’s high school had become an accredited four-year school. Enrollment increased significantly necessitating the need for a new high school building. A new brick building was ready for classes in the fall of 1920 at a cost of about $33,000. The new building had the added bonus of a gymnasium. At this time, there were approximately 30 students and three faculty members in the high school. Rosamond James Eves and Oscar Maddux were the first two graduates from the new high school in the spring of 1921.

Coal-burning furnaces gave way to more modern gas heating systems in the 1920s, and 1948 marked the end of the school system’s private water system as water was then provided by the Deerfield’s city water system. Indoor rest rooms were installed and first used in the old grade building in 1951.

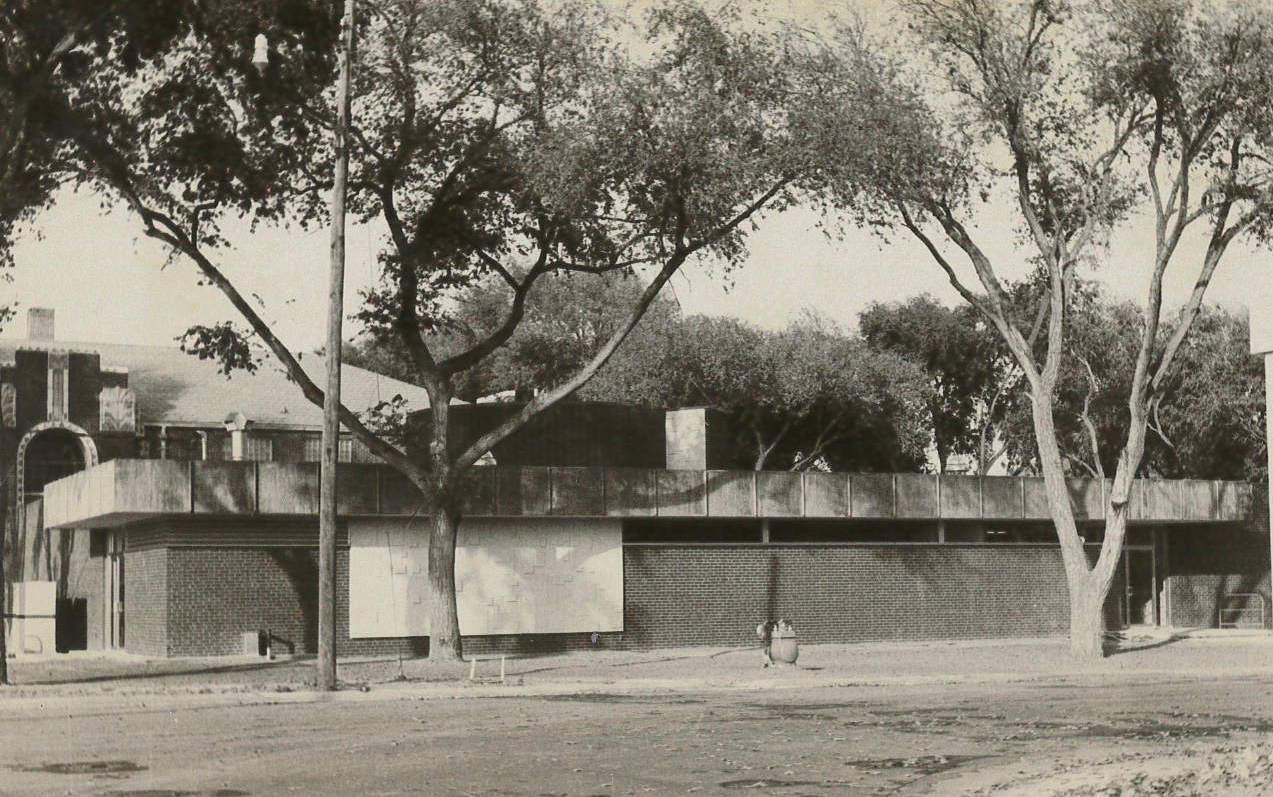

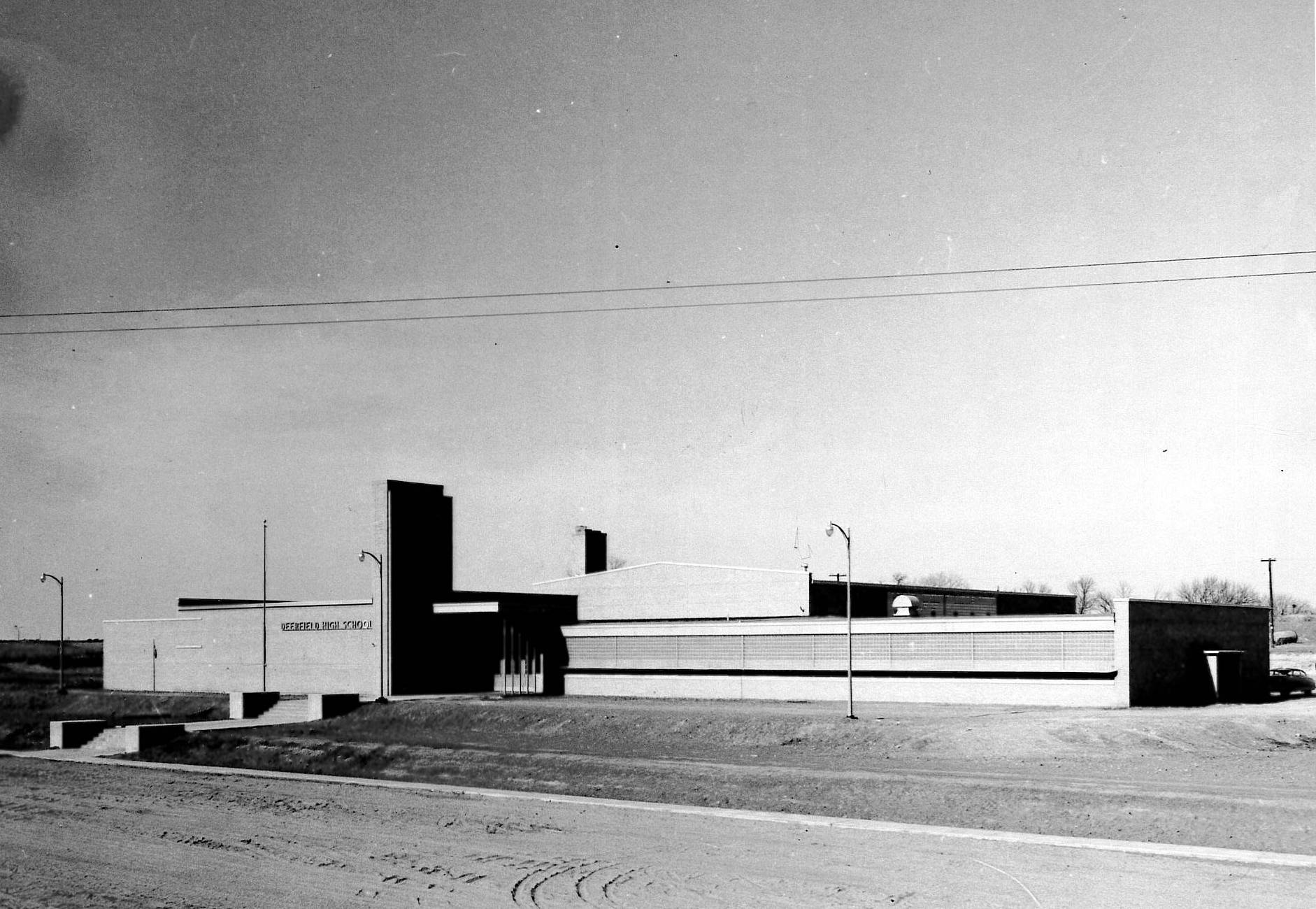

In 1946, the rural Prairie View and Harmony schools consolidated with the Deerfield Grade School while Pleasant View School District was added to the Deerfield district the following year. With added students and overcrowded conditions, Deerfield High School District No. 3 voted to build a new high school. In February 1950, 46 students and faculty moved into the $330,000 building.

Meanwhile, more space was badly needed at the grade school. A lunch program was added which required space for a kitchen and dining room, and the addition of a music room further depleted the available classroom area. More elementary teachers were added which ultimately provided a teacher for each grade. Since there were not eight classrooms available, the seventh and eighth grades were housed in the old brick high school from 1951 until 1957. After considerable groundwork, a bond election was held in January of 1956 in which bonds in the amount of $294,000 were approved for building and equipping a new grade school which would house kindergarten through eighth grades as well as a lunch room. Construction began in September of 1956, and the school was ready for occupancy in October of 1957. An estimated crowd of 300 people attended the dedication of the building on November 11, 1957. The school’s all-purpose hall was also dedicated that day in memory of Rex Miller, a member of the school board who had perished in an explosion in August of 1956.

The two old brick school buildings were razed, and recently city crews uncovered some of the bricks from the buildings when they were installing a new sewer extension for lots north of Deerfield’s tennis courts and swimming pool.

SOURCES: History of Kearny Co. Vol. I; archives of The Advocate and Lakin Independent; “Deerfield School Advancement” by Norval Gray, Supt. Of Deerfield Schools 1951-1962; information provided by the late Mary Russell, granddaughter of H.Charles and Belle Nicholls; and Museum archives.

Although numerous outdoor enthusiasts, families and scout troops enjoyed Lake McKinney’s benefits, the reservoir was also the sight of several tragedies. The first of many drownings occurred on the second day that the lake was being filled, Feb. 12, 1907. John Phillips, Harry Beckett and Fred Frost went to the lake to complete some unfinished work. They were returning to Lakin in their wagon when they came to a spot where water covered the road. Certain that they knew where the road was and that the water was shallow, the men decided to cross the strip instead of going around. Frost turned the team of mules into the water. Head surveyor Henley Hedge was following them in his buggy and watched as one of the mules slipped off the road bed into deeper water, pulling the other mule and wagon in after him. Hedge jumped into the icy water, cut the mules free and managed to pull Frost to safety. Hedge pushed into the cold chilly water to rescue Phillips, but Phillips refused to take hold of the pole extended to him. Both Phillips and Beckett drowned. Beckett was the rodman and chief assistant to Phillips, a rising young civil engineer who had been the engineer in charge of the project.

In July 1908, 14-year-old Fred Schagun of Deerfield drowned when he and his brother were fishing. The boy waded into the water to unfasten his tangled line and got into one of the channels where water was several feet deep. In February 1909, 17-year-old Gilbert Kimball was mortally wounded while on a hunting expedition with his brother and four friends on the east side of the lake. The Lakin teen was getting out of a surrey when his gun inadvertently discharged, the ammo hitting Kimball in the throat. Clarence Parcells died a month later after being shot while hunting ducks with a number of other Lakin businessmen at Lake McKinney. The 24-year-old Parcells was inside a hunting blind with Charles Waterman and stepped in front of Waterman’s gun just as he pulled the trigger.

In August of 1910, teachers James Hemphill, Frank Hibner and Will Bruner rowed their boat about 200 feet from shore and anchored it in order to fish. Noticing their team of horses which had been tied on the bank was loose, the 24-year-old Hemphill jumped into the water and began swimming to shore. Hemphill had swam about 50 yards then called for help but could not be reached in time. Seventeen-year-old Eulojio Montoya drowned in July 1922. He had come from New Mexico to work in the sugar beet fields and was with four companions, all of whom jumped from a leaky boat when 150 yards from the bank. Montoya was seized with cramps while swimming to shore.

Milton Clare Downer, 22, of Garden City, drowned in August of 1946 when the boat in which he was riding capsized in about eight feet of water. Downer could not swim. Thirty-five-year-old Ray Barrett of Syracuse drowned while attempting to swim to shore after his motorboat overturned in June of 1948. Barrett was approximately 500 yards from shore. The lake at that time was described as rather windy with raising six-inch high waves. In July that same year, a Garden City family of four drowned when the two-man boat they had borrowed was swamped by waves and capsized. Clarence and Angeline Jansen and their young sons, ages 3 and 4, were fishing in the middle of the north end of the lake. A fifth person in the boat, Preston Jones of Garden City, managed to fasten himself to the side of the boat and stay afloat until he attracted the attention of fishermen on the shore.

In December of 1953, Sam McGinness was hunting ducks and apparently had gone after one that had gone down on the ice. The 49-year-old Garden City man broke through the ice nearly 400 yards from shore. McGinness’s cries for help were heard, but he drowned before rescue boats could reach him. Orval Glancy, 55, of Garden City, lost his life when he fell from a small speedboat while fishing in September 1957. After searching futilely for 15 minutes, Glancy’s companion summoned for help. Glancy’s body was found after a seven-hour search. Garden City brothers, Gary and Larry Gossman, ages 12 and 13 respectively, drowned in May of 1959. They were on a 12-foot fishing skiff with five other passengers when their boat was swamped by high waves fueled by 30 to 40 mph winds. Another boat took three of the passengers to a nearby fishing raft and returned for the brothers and their parents, but while trying to pull them into the rescue boat, the boat that the Gossmans were in capsized.

Seventeen-year-old John Yager Jr. was on his way to see his parents at Lake McKinney in June 1962 when his car went out of control and rolled into an irrigation ditch that filled the lake. The Lakin teen was pinned under the car which was in about two and a half feet of water. The other occupant in the car, Robert Yoxall, attempted to free Yager but was unable to do so and ran about three quarters of a mile to a field where Jim White was working and collapsed. White revived Yoxall and phoned officers for help when he learned of the accident. The car was lifted using a chain and jeep belong to White, but Yager was pronounced dead at the scene.

In April of 1970, Joseph Randolph of Lakin was hunting with two friends at the spillway bridge where the Amazon diverted into the west end of the lake. The gun of one of Joe’s companions accidentally discharged, and the bullet struck Randolph in the head. The 16-year-old Randolph was taken to Kearny County Hospital for treatment and then flown to Wesley Medical Center in Wichita where he died three days later. In 1972, a young Wichita father was killed instantly when his car plunged from a low dike on the east shore which ran from the recreation area near the boat docks. Charles Heuett apparently attempted to pull his car back when it went out of control on a sharp curve, but the car flipped and then landed on Heuett who was ejected. The 35-year-old suffered multiple injuries including a skull fracture.

In June of 1998, 16-year-old Tiana Marie Vasquez went to the lake with three of her friends to swim. The Deerfield girl immediately disappeared after jumping in near the spillway. She was apparently dragged under by the strong undercurrent and sucked through the spillway as her body was recovered in the Great Eastern Ditch about a mile and half from where she jumped into the lake. Vasquez’s drowning was tragic and serves as a sad reminder about the dangers of trespassing on public property. Since Lake McKinney closed to the public in 1978, there has occasionally been scuttlebutt about re-opening the lake, but the fact remains that the lake and the surrounding property is owned by The Garden City Company. The only people allowed on the property are company personnel and persons who have been given prior authorization.

Sources: Diggin Up Bones by Betty Barnes; History of Kearny County Vols. I & II; Archives of The Garden City Telegram, The Advocate, Lakin Investigator and the Lakin Independent; and Museum archives.

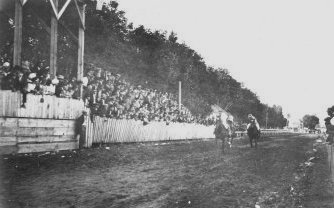

The Kearny County Fair is a long-standing tradition that began in 1914 in a shady grove just west of Lakin. The fairgrounds were west of present-day Bopp Boulevard between Lincoln and Railroad avenues on the timber claim of F.L. Pierce where he had planted walnut, Osage orange, cottonwood, locust, catalpa and mulberry trees in the 1880s. Through Pierce’s continued efforts, the fairgrounds became a shady picnic ground. A large grandstand sufficient to hold 400 or more people overlooked a half-mile race track and baseball park, and amusements and lunch counters dotted the grounds under the shade of the walnut trees.

The highly anticipated fair opened Thursday, Sept. 24, and attendance for the first two days was estimated at 1,100. Even Lakin’s schools closed so that all the children and teachers could have the opportunity to attend. The Lakin Independent reported that Pierce, who was the fair association’s secretary, “was in the ticket office shoving out the tickets and gathering in the nickels. Crowds from the four corners surged through the ground looking over the displays of machinery, farm products, horses and cattle, quilts, needlework, finery, etc.” To maintain order and make all fair visitors feel at home, the fair association recruited a squad of mounted police.

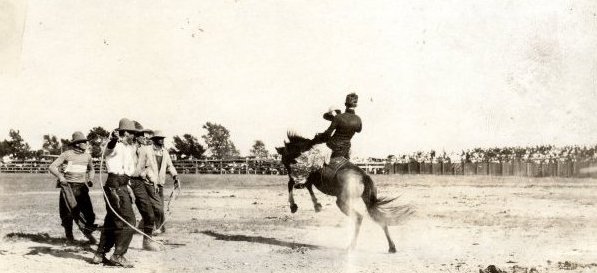

Horse racing was a big draw of the fair. Good purses attracted owners of some of the best horses in the country. Categories included pony racing, horse racing, ladies riding, Roman racing, harness trotting race and a relay race, but the racing was not limited to horses. There were also foot races, auto races and dog races. Other competitions included wrestling, a potato race on horseback, a sack race, bucking broncos, greased pig contest, and a challenge to see who could stay under long enough in a tub filled with water to secure a big silver dollar with their teeth. Fair-goers were also entertained by the Lakin band, the “hippodrome” or equestrian riding performance, and pole-vaulting demonstrations. A baseball game was played in the late afternoon each of the three days, and every game was called before ending because of darkness. Lakin, Deerfield, Midway and South Side were the competing teams, with Deerfield taking the championship game, 5-3.

That year was a very good year for gardeners, and produce entries ranged from grapes and sweet potatoes to an 80-pound pumpkin. Crops of wheat, corn, rye, oats, and broom corn were also entered. The poultry department had a good showing of geese, ducks, turkeys and chickens. Mules, a fawn and even guinea pigs were on display. Baked goods, handiwork and art rounded out the line-up.

The Oct. 2, 1914 Advocate declared, “The fair is over and success is written in large letters by the large number of people who attended the exhibition.” The Kearny County Fair Association attributed much of the fair’s success to local farmers and other exhibitors but also gave credit to those from Grant County who had entered items in the fair.

The movement for a county fair and fairgrounds had begun two years earlier. Stocks in the Kearny County Agriculture and Fair Association were sold for $10 each, and a board of directors was elected in the spring of 1914 to lead the organization. The association secured a membership in the Grain Belt Racing Association in May of 1914, and the fairgrounds were officially opened on June 13th with a running race between George Rider’s and William Gillespie’s horses followed by a baseball game.

The annual fair took a hiatus in 1918 and 1919 during World War I but resumed in 1920. As time progressed, more buildings were added and amusements and lunch counters increased. The fair took on a carnival air adding such amusements as a tug-of-war between communities, motorcycle races, airplane exhibitions, and a fat man’s race. The hard times of the 1930s forced the fair association to disband and dismantle its buildings and discontinue the fair. About that time, 4-H club work was started, and the annual fair became a 4-H event. A location was hard to find so booths and home economics projects were displayed in stores, the courthouse or wherever possible. Livestock was exhibited in some vacant lot, in the lumber yard or on a town street where trees could provide shelter. A few interested persons started working on a regular location for a fair and other entertainment early in 1950. Many were interested in horses so the Kearny County Saddle Club was organized, and Mr. and Mrs. Charles A. Loucks deeded a tract of land where the rodeo and fairgrounds are now located.

When county commissioners were preparing their budget for 1957, they approved the allocation of funds to operate a free county fair and the establishment of a fair board. Although the fairs may look differently than they did in the 1900s, commissioners, fair boards, the Kearny County Extension Service, 4-H groups, Kearny County Saddle Club, and other organizations, businesses and individuals have worked cooperatively through the years to ensure that the tradition that started over a century ago continues.

If you get the opportunity, venture out to the rodeo and fairgrounds this weekend and next week to partake in the fun at the Kearny County Saddle Club’s annual amateur rodeo and the Kearny County Fair! And don’t forget to attend the rodeo parade Saturday morning at 10 a.m. followed by a free ice cream social at the Kearny County Museum!

Sources: History of Kearny County Vol. I; Advocate and Lakin Independent archives; museum archives.

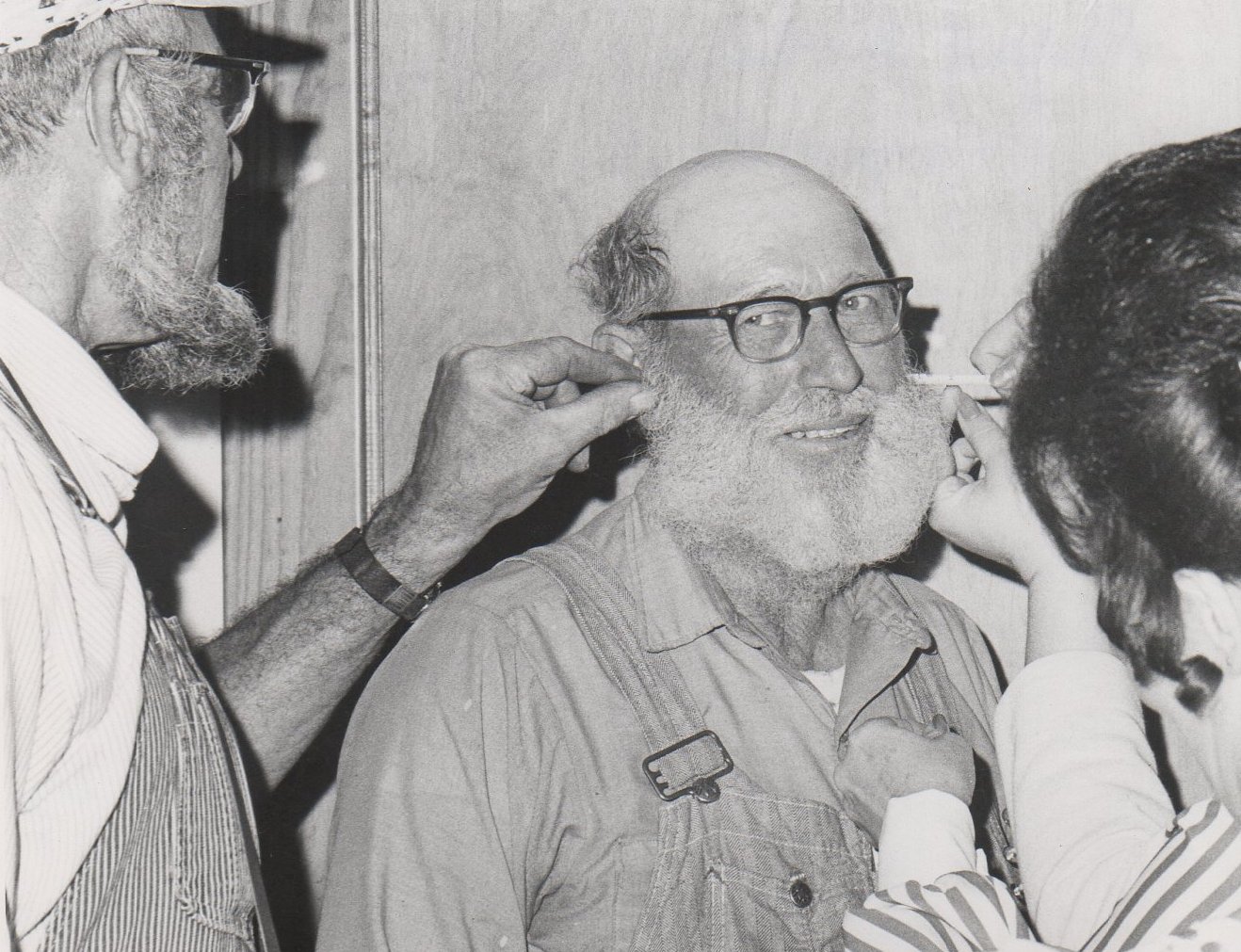

Visitors to Lakin in 1973 may have thought they had entered a time warp. Ladies in pioneer dresses and bearded men were a common scene as the community celebrated Lakin’s 100th birthday in a stylish year-long celebration. The “fuzz” phenom was the result of a beard and mustache contest, and some men began growing their facial adornments as soon as the year started. For beardless wonders, shaving permits could be bought for $5 each to save a fine or a dunking. The Blossom Club requested all women who were working downtown (and shoppers too) to wear pioneer dresses on Fridays in observance of the centennial year. Those who opted not to either faced a fine or wore a permit that was sold by the club for 50¢.

Many kept the permits as souvenirs for the big occasion. Other specially made souvenirs included plates, coins, car tags, and special edition Winchester rifles. A seal picturing key events and industries in Lakin was created for use on advertising materials to call attention to Lakin’s “big 100.” The seal was designed by Don Musick, a former Lakin High School principal whose painted school mascots adorned many gymnasiums in Kansas including Lakin’s.

Pitchers of beer, soft drinks, and food were available at the Centennial Ale House which was set up a half block west of Main and Waterman in a building that was owned at the time by Guy McCombs. Musical entertainment was also on tap there. The beer garden was the brainchild of a group of Lakin women who voluntarily worked the venue to raise money for centennial activities. The grand opening was held April 13, and the ale house was open to customers several Friday and Saturday nights throughout 1973.

Also in April, Gladys Hoyt and Ruben Maerz were selected as Queen and King by Lakin Manor residents and staff to represent the manor in centennial events. An old-fashioned basket dinner and hymnfest were conducted later that month at the Methodist Church under the direction of Rev. Duane Harms.

Former Lakinites came from all over the country to attend Centennial Days June 1-3. Frances Bostrom of the Lakin Booster Club was the chairman and coordinator of the big shindig which took the cooperation of dozens of organizations and scores of individuals to successfully orchestrate. The V.F.W. Auxiliary assembled a display of historic significance in the Memorial Building and served chuckwagon lunches on Friday and Saturday and a dinner on Saturday night. Job’s Daughters held old-time ice cream socials Friday and Saturday afternoons at the Masonic Temple, and the Museum, located in the building now housing Golden Plains Credit Union, was open all three days. A carnival with rides was a major attraction for the kiddies.

The Lakin Methodist Women held a rummage sale, and the Lakin Young Women’s Club conducted a pie sale on Friday. That evening the Lakin 50 Club presented a fashion show featuring yesteryear fashions modeled by beautiful young girls and distinguished dames. The Rhythm Rangers played a dance to close out the day’s events. On Saturday, Homemakers E.H.U. hosted a bake sale, and the Civic and Study Club served hot homemade bread and rolls from the Country Kitchen in the Memorial Building. The afternoon parade was seven blocks long and had 49 entries with winners chosen among both the float and antique car entries.

Shortly before the parade started, a “raid on the village store” was staged for the amusement of the crowd which had gathered on Main Street. Desperadoes Jon Wheat and Stephen McCormick entered Gary’s Grocery and demanded the hidden money sacks. The dastardly duo fled the scene after taking Janice Spencer Urie, an innocent bystander, as hostage. Gary Hayzlett, the irate storekeeper, pursued the bandits with his famous Civil War musket in hand. According to the Lakin Independent, “the scoundrels escaped to their hideaway on the shores of Lake McKinney.”

There were 47 entries in the beard and mustache contest which was judged after the parade. Awards were presented in eight categories with Warren Elliott awarded for fanciest beard and best all-around. Don Bemis won the longest beard category, Charles Hannagan won for fullest beard, and Paul Garcia won for whitest beard. Winning honors for their mustaches were Floyd Schwindt, longest mustache, and Everett Moreland, best trimmed mustache. The Rainbow King hosted a free dance that evening. The weekend’s festivities concluded Sunday with the LaFlora Garden Club and Ministerial Alliance hosting an old-fashioned picnic in the City Park.

There was plenty of do-si-doing going on at the outdoor square dance sponsored by the Lakin Square Dance Club the following weekend, and in July, an enthusiastic and appreciative audience came out to boo the villain and cheer on the hero in an old-fashioned melodrama put on by the Centennial Players at the high school auditorium. Admission was 11¢ or free if wearing centennial garb. Six lucky participants won Shetland ponies in the Shetland pony scramble at the Kearny County Saddle Club’s Centennial Rodeo July 21 and 22. Other events that weekend included the annual Rodeo Parade, an old-fashioned chuckwagon BBQ and a dance at the Ale House. The Santa Fe Railroad’s Centennial rail car was also in Lakin.

A baby beautiful contest for persons 65 and older was one of many activities added to the county fair in August. Ruby Enslow and Oliver Coder won the TOPS-sponsored event. Lakin’s birthday got special attention when Brad Tate arranged for August’s feature race at Santa Fe Downs to be called the Lakin Centennial Stakes. A chartered bus of race horse owners and racing fans from Lakin attended the competition, and Lennus and Frances Bostrom had the honor of presenting a cooling blanket to the winning horse’s owners.

September’s Centennial Art and Antique Show featured the art work of several area artists and an array of vintage items, and the Centennial Christmas Parade in December was called the best ever. Blessed with perfect weather, a large crowd gathered to witness the event which was preceded by an old west shootout on Main Street between a group of bad men from the sandhills and keepers of the peace who were concealed on the roofs of buildings. After the smoke cleared, the posse loaded up the losers in the farm wagon they came to town in and cleared the street for the parade. Lakin’s big birthday year wrapped up with a “Harvey House” Centennial Christmas Luncheon Dec. 21 which was sponsored by the Kearny County Council on Aging and Budget Shop. The program was centered around Lakin’s early railroad history.

The year closed, beards were shaved, and pioneer clothing was packed away. But the memories of 1973 would live on in the hearts and minds of all those who were lucky enough to take part in Lakin’s big 100th birthday bash.

SOURCES: 1973 Lakin Independent archives. History of Kearny Co. Vol. II, Museum archives, and mikelynchcartoons.blogspot.com

A walk, drive or bicycle ride through Lakin is a journey through our past. Old buildings that housed some of our earliest businesses and former homes of pioneering residents can be found throughout town, and even street names are a link to those who came before. While some of our streets may have been named for presidents or early Kansas dignitaries, several were named for locals and people with Lakin connections.

Waterman Avenue was once the main thoroughfare through Lakin and runs from Cemetery Road on the east edge of Lakin to Bopp Boulevard on the west side. The street was named for James Waterman who came to Lakin in 1880 in the employ of the Santa Fe Railroad. Waterman had many occupations during his tenure here such as newspaper editor, postmaster, business owner, farmer and rancher. He was also appointed first county clerk by the governor in 1888.J

Located in the northeast part of the city, O’Loughlin Street was named for founding father John O’Loughlin and his family. This street intersects with Russell Road on the south and Thorpe Street on the north. Billy Russell came to Lakin in 1881 and worked nearly 40 years for the Santa Fe Railroad, and the Russell family’s former home still stands at 808 E. Russell Road. Thorpe Street was named for Thornton N. and Ettie Thorpe. The Thorpes came to Kearny County in the 1880s, and T.N. represented Kearny County for four years in the Kansas House of Representatives. The Thorpe name is well documented in county history for contributions to our community.

Osborn Drive runs beside Osborn Park which was originally the location of the Osborn family home. Bert Osborn worked 53 years as Santa Fe agent and telegrapher, 42 of those years in Lakin. He and his wife, Ethel, were very community-minded and had a petting zoo, swimming pool, duck pond, and rock garden on their property.

Soderberg Street near St. Anthony’s church was named for David Soderberg who was in charge of the building operations when the Kearny County courthouse was built in 1939. The son-in-law of Clyde Sr. and Ethel Beymer, he was married to their daughter, Cledythe. Soderberg was killed in a car accident west of Wichita on Christmas Day of 1945.

Simshauser Street is located in the Simshauser subdivision in east Lakin which was established by Norman and Ethel Kleeman Simshauser. A World War II veteran, Norman moved with his family to Kearny County at the age of one and lived the remainder of his life here except for his time in the service. Ethel was born in Kearny County and lived here all of her 92 years. The Simshausers were both very active in community organizations such as the Kearny County Historical Society, Senior Center, VFW and EHU as well as the Immanuel Lutheran Church. Norman also served on the City Council and Veteran’s Memorial Building board.

Harold’s Place is located in the White Subdivision near Kearny County Hospital and is named for Harold White, native Kearny Countian, farmer, rancher, and Army veteran. Harold also served on the Kearny County Farm Bureau board of directors as president. White subdivision was created in 1974 by Harold and his mother and also includes Thelma Drive which was named for Harold’s wife. Thelma owned and operated Antiques ‘N Things and was very involved with the Lakin Presbyterian Church.

West of Main Street, Campbell Street runs from HWY 50 to Railroad Avenue and was named for early pioneer James Campbell.

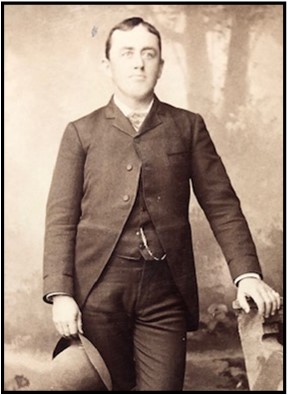

Campbell came to Kearny County in 1886 and served as sheriff when the county seat was moved from Hartland to Lakin. He also served two terms as county commissioner.

Kendall Avenue flanks Thornbrough Park on the south. One block north is Wayne Avenue. These streets are part of the Thornbrough Subdivision and named for cousins Kendall Campbell and Wayne Thornbrough. Both of these Lakin High School graduates lost their lives while serving in World War II.

Robroyce Avenue lies one street south of Kendall Avenue and was named for two young LHS graduates who died in 1973. Rob Wiley was 20 years old when he was killed in a vehicle accident, and Royce Burch died at the age of 22 after undergoing surgery for brain tumors.

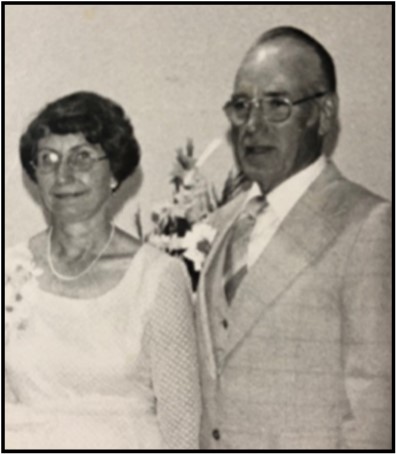

Smith Avenue is three blocks south of Robroyce. To the west in this vicinity was the Charles S. Smith place where Lakin’s first cemetery was located. It was just a burial place out on the prairie, and most of the people were buried in rough pine boxes without being embalmed. About 40 graves accumulated in this place. The graves were transferred to what is now the Lakin Cemetery about 1892. According to the first volume of History of Kearny County, a few of the bodies remained in their original resting place. The Raymond and Rose Smith family lived at the east end of the block where Smith meets up with Campbell Street. Raymond Smith was a lifetime Lakin resident. A farmer, he married Rose in 1934. They were the parents of former Kearny County Museum director Harold Smith.

Bopp Boulevard is in the Gropp addition and is the farthest street west that runs all the way from HWY 50 to Railroad Ave. This was named by Ralph Gropp in honor of his mother’s family, and Mattie Street was named specifically for his mother, Mattie Bopp Gropp. Frank and Sarah Bopp came to Kearny County in 1886, and all three of their daughters became teachers. In 1912, Mattie married Albert Gropp, a farmer, rancher, brand inspector, and member of the Gropp family who located on a homestead near Kendall in 1887. Albert Street, one block west of Bopp, is named for him.

Edward Loeppke purchased 30 acres on the west edge of Lakin in 1945. The Loeppke Subdivision was established in 1958 and includes the following street names: Loeppke, Edward, Sarah, Kraus, and Tampa. Edward Loeppke and Sarah Kraus were married at Tampa, Kansas in 1905 and came to Kearny County in 1930 where they were engaged in farming. They had seven children, several of whom had homes in this subdivision and were involved with local organizations, schools and churches.

Nabocoho Lane is often referred to as Airport Road and sometimes White Road. The origins of the name, “Nabocoho” were somewhat of a mystery until recently when museum staff happened across an article written in 1990 by Thelma Leonard. Thelma explained that the Civic and Study Club took on the project of getting street signs for Lakin in the 1950s, and club member Gladys Hoyt wanted her road to have a proper name. Gladys took the first two letters of the surnames of the first four families who lived on the road between Highway 50 and the south branch of the Great Eastern Canal—Bernard and Kay Nash and Bernard’s mother, Ann Nash; Jake and Olive Bodam; Delbert and Marjorie Cox; and N.E. and Gladys Hoyt—and came up with Nabocoho. The C.A. Leonards lived on the road in the house closest to town, and Gladys wanted to incorporate their name as well. She decided on “Lane” as it began with L, and all four letters of the word are also in “Leonard.”

When you are out and about in our little town and spot these street names, perhaps you will now think of the people for whom they were so fondly named.

SOURCES: Earle D. Rice, LHS graduate and former owner of Kearny Co. Title Company; History of Kearny Co. Volumes I & II, Digging up Bones, and museum archives.

*Kearny County Museum does not have pictures on file for each person mentioned in this article.