As if the Dust Bowl didn’t make matters difficult enough, a deluge of grasshoppers made the bleak farming situation of the 1930s even more complicated. To battle the pests and ultimately save his alfalfa crop, Orlie White began raising turkeys on his Kearny County farm located on the north shore of Lake McKinney. According to a story written by his wife, Prudence, “Turkeys were the best grasshopper catchers in the world.”

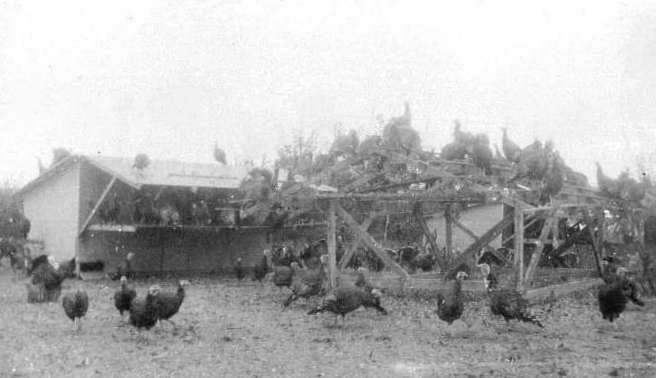

Orlie had a dealership with Red Wing Hatcheries in California for ‘broad-breasted turkeys,’ an improved meat bird. The poults arrived by freight train, and each was taught to drink water and then put in a heated brooder house for the first few months. White built three brooder houses to house 1,000 poults the first year. These structures were on skids so they could be pulled by horse or tractor to fresh ground and a new supply of grasshoppers, sometimes as often as every two to three days. These moves were also made to lessen the threat of a disease called blackhead to which the turkeys were very susceptible. In making these moves, the feeders and roosts were pulled slowly a quarter to one-half mile to the new location. Sometimes the turkeys would follow, but more often than not, they had to be driven.

“If a few managed to get away through the line of drovers, the whole flock would suddenly turn, and half-flying, stampede back to the old location,” wrote Prudence. Drovers would have to protect themselves as best they could from the onslaught of “hurtling birds, flapping wings and choking dust.”

Later, the Whites added three more houses, and increased the number of poults to 2,100. In summer, portable roosts were built as turkeys “have a yen” to be put out in the open at night. To keep coyotes, coons and other predators at bay, lighted lanterns and sometimes even flares were put around the turkeys and someone slept near the turkeys each night.

Severe dust storms could also prove fatal to young birds. A particularly severe dust storm hit April 9, 1935 and was still raging two days later. Because of the storm, the White’s telephone was not working, and it became necessary for Orlie to ride a horse into Lakin and send a telegram to Red Wing asking them not to send the poults until further notice. When the dust storms died down about two weeks later, the Whites ordered the turkeys again.

Quite a bit of work had to be done before receiving the poults. Boiling hot water was used to scrub the fourteen feeders and water fountains. The brooder stoves were checked out to make sure they were working perfectly, and litter was spread on the floor of the brooder houses. As turkeys tend to crowd into corners and trample or smother one another, the Whites rounded the corners in the brooder houses with wire netting.

On April 29, 1935, Orlie met the early morning train and soon returned with 17 boxes of poults, each box containing 60 poults. Each was given a drink before being set loose in the brooder houses, and in a week’s time, “the little gobblers were strutting.” On May 27, a haziness appeared in the sky, and Prudence drove the little birds from their pen enclosures into their houses. She was not a moment too soon as the storm came fast and she had barely enough time to get them all inside.

“A cloud of darkness settled over us and stayed that way about 20 minutes. Then it began to rain, hail and blew so hard that large branches were broken off the trees. Eventually, the clouds broke, and we could see the Amazon ditch overflowing its banks, and deep water swept through the recently evacuated turkey yards. I shall always recall my good fortune in that I went to check on the small turkeys before lying down with the baby,” Prudence recalled.

Pilots from the Garden City Army base often flew overhead and would dip low enough to see the turkeys which caused the birds to panic. The pilots didn’t realize how much trouble they caused.

“In fact, a hawk flying overhead could cause a like disturbance. Any unusual noise in the middle of the night could send all of them into flight. . . Turkeys could think up the most novel ways to commit suicide, sometimes by hanging themselves on a piece of machinery.”

Because the gobblers required constant watching, the White family was closely confined at home when raising turkeys. They enlisted men to help with the operation, but the World War II draft resulted in a shortage of hired help. Two of their men, James D. Porter and Lawrence Epperson, were called into the service, and both gave their lives for the cause.

White’s turkey business ended by 1942. In addition to saving their alfalfa, the venture also ended up being very profitable for Orlie and Prudence who marketed their birds for the Thanksgiving and Christmas seasons at the Swift plant in Garden City. “We always figured we made at least a dollar per head on every poult we bought.” By 1938, the White’s home had let so much dust in that they had a new one built. According to Prudence, the completed house and furnishings in pre-war 1938 cost $11,000 and was paid for with “turkey money.”

Orlie and Prudence were not the first large-scale poultry producers in Kearny County. According to the Nov. 19, 1904 Investigator, Barney O’Connor was the first poultry dealer here to ship carloads of turkeys out by train. O’Connor loaded his first car on November 15, 1904, and approximately 850 fine gobblers made their way across Kansas and to the Kansas City market courtesy of O’Connor and the Santa Fe Railroad.

Here’s wishing all of our followers and friends a very Happy Thanksgiving!

May your turkey be tasty! The Museum will be closed Thursday and Friday.

SOURCES: History of Kearny County Vols. I & II; archives of the Investigator and Museum archives.