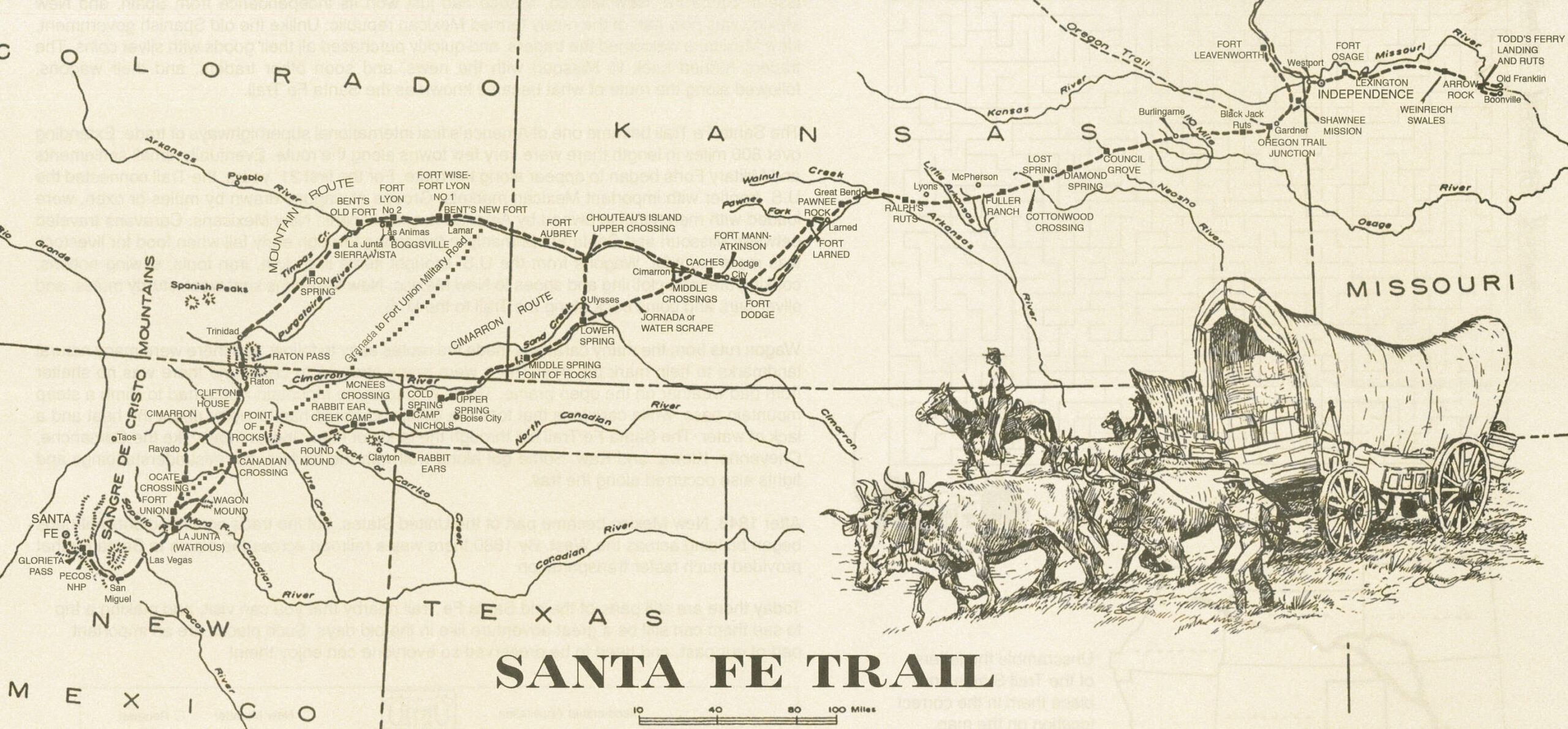

Indian Mound and Chouteau’s Island, both in Kearny County, were the most conspicuous landmarks on the Santa Fe Trail between Pawnee Rock and Bent’s Fort. One can only imagine the array of traders, soldiers, freighters and emigrants who passed through our ‘neck of the woods’ while traversing America’s first commercial highway.

In September of 1821, Missouri trader William Becknell left Franklin with wagonloads of cloth, buttons, buckles, tools and more. It took him and his five compadres roughly two and a half months to cross Kansas and reach Santa Fe, NM. Unlike others before him who had been arrested by Spanish soldiers, Becknell was welcomed. What was so important about Becknell’s timing? He had made it to New Mexico after the territory won its freedom from Spain. He returned to Missouri with bags of silver and glowing accounts of the profits to be made in the Santa Fe trade. Other traders soon followed suit.

By 1824, commercial trade between Missouri and New Mexico was a significant benefit to both the U.S. and Mexico. That year, the General Survey Act authorized the president to order surveys for roads and canals “of national importance, in a commercial or military point of view, or necessary for the transportation of public mail.” President James Monroe assigned responsibility for the surveys to the Corps of Engineers. The act provided $10,000 for marking the Santa Fe Trail and $20,000 for implementing right-of-way treaties with Native American tribes whose land touched the route. The Sibley Expedition began the nearly two-year endeavor in July of 1825.

There were two routes to the Santa Fe Trail, the Cimarron Route and the Mountain Route. Just west of Dodge City, some traders crossed the Arkansas River at the middle crossing to take a shortcut called the Cimarron Cut-off or the Jornada. This route was very dangerous because it passed through Indian hunting grounds and very little water was available. Wagons that did not take the Cimarron Cut-off continued west beside the Arkansas River, eventually arriving in what is now Kearny County. Here, caravans had two choices – continue west and take the treacherous mountain route which offered more water and fewer Indian dangers or use the upper crossing, turning near Chouteau’s Island and traveling the Bear Creek Pass.

According to field notes by U.S. Engineer Joseph C. Brown, a member of the Sibley Expedition, “The road is again very good up to Chouteau’s Island – the largest island of timber on the river. Many things unite to mark the place so strongly that the traveler will not mistake it … On the north side of the river the hills approach tolerable nigh and on (one) of them a sort of mound conspicuous some miles distance. . . The course of the river likewise being more south identify the place.”

Indian Mound, about five miles west of Lakin, overlooked Chouteau’s Island. Speculation regarding the origin of the mound is longstanding. Was it manmade or a phenomenon of nature? Whatever the case may be, Indian Mound offered a vantage point to both settlers and Native Americans on the lookout for approaching parties. Wind and rain have eroded the mound considerably.

Chouteau’s Island once rose lush and green in the middle of the Arkansas River. Its disappearance is blamed on natural forces, flood control measures and the use of the Arkansas for irrigation. The island was named for Auguste P. Chouteau whose hunting party entrenched themselves on the island in 1816 and successfully fought off an attack of 200 Pawnee Indians.

Wagon trains turned south at Chouteau’s Island and skirted the small but very deep Clear Lake, noted by Brown as a large pond slightly to the east. They then followed Bear Creek Pass, a natural passageway through the sand hills created by a slippage in the Cretaceous Formation around 250,000 years ago. According to geologists, a stream flowed through Bear Creek into the Arkansas River, but dry periods led to the sand blowing over the water and the stream going underground. This theory rings true with what is known of Sunken Wells, a watering hole and stopover point near the Kearny-Grant county line. Stories tell how travelers would stop for the night in the dry sand hills with no water in sight. They would wake in the morning and were surprised to find large cracks in the earth near where they had been sleeping and a lake of water, 200 feet or more in diameter. Within a few hours, the lake would disappear. From this southern end of the Bear Creek Pass, travelers struck a due south course until meeting up with the Cimarron Cut-off at the lower spring (Wagon Bed Springs) in what is now Grant County.

By 1825, goods from Missouri were not only being traded in Santa Fe but also to other points farther south. In 1828 alone, $150,000 of merchandise was taken to Santa Fe. By that time, Independence, MO had become the starting point of the trail. The trail was used primarily as a commercial road between 1821 and 1880 and quickly became a route of cultural exchange. A few months into the Mexican-American War in 1846, America’s Army of the West followed the Santa Fe Trail westward to successfully invade Mexico. Following the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo which ended the war in 1848, the Santa Fe Trail became a national road connecting the more settled parts of the United States to the new southwest territories. According to the National Park Service, commercial freighting along the trail boomed to unheard-of levels, including considerably large amounts of military freighters who were supplying the southwestern forts. The trail was also used by thousands of gold seekers heading to Colorado and California, stagecoach lines, adventurers, missionaries, wealthy New Mexican families and emigrants.

Railroads began expanding westward across Kansas when the Civil War ended. Shipping goods by train was faster and easier, and the lengths that traders had to travel on the trail grew shorter. The glory days of the oldest and most important overland trade route across the Great Plains were over when the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad reached Santa Fe in 1880.

SOURCES: National Park Service; Santa Fe Trail Association; “Bear Creek Pass and the Santa Fe Trail” by Dorothy Morgan; History of Kearny County Vol. 1, and Museum archives.