Summertime is synonymous with fishing trips, fireworks, baseball, homemade ice cream AND watermelon. Who wouldn’t want to sink their teeth into a juicy red Black Diamond when the temps are sweltering? Did you know that Kearny County farmers once grew some of the best watermelon in the nation, and instead of being used for human consumption, a large percentage of the melons were harvested for their seeds?

Vine crops like watermelon, cantaloupe and several varieties of musk melons were some of the first crops grown in the county, particularly on the South Side. They were irrigated with a windmill or a small ditch from the river. As neither of these two means could supply a large amount of water, only small acreages were planted. Before long, the need for larger irrigation ditches to supply water to larger fields was recognized.

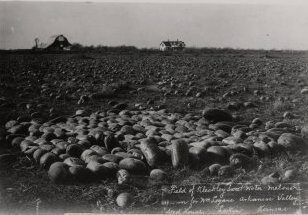

Water from irrigation ditches fueled by the Arkansas was plentiful, and melon raising became a very important industry all along the Arkansas River Valley. Immense vine crops were grown in the 1890s for the D.M. Ferry Seed Company of Detroit, and it was not unusual for farmers to have 50 to 80 acres apiece planted to melons.

The land was carefully prepared for melon planting with seeds planted in rows some four or five feet apart giving adequate room for the vines to grow and produce the delicious fruit.

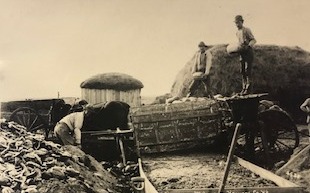

Harvesting came in the latter part of August and September. Melons were pulled from the vines and piled in the field waiting for the “melon grinder.” The grinder was an ordinary lumber wagon rigged with a wire-covered reel running the long way of the wagon box. A crank was fastened on the end of the reel at the back end of the wagon, and a knife was attached upright to the reel up front. There was a large box kept full of over-ripe melons under the knife. The man standing behind the box would throw a melon into the turning reel allowing the seed to fall through the mesh wire into the wagon box. The melon halves rolled out the back end of the reels into piles. These melons were fed to both hogs and cattle.

When the wagon box had the desired amount of seed in it, a gate under the crank was opened and the seed drained out into a tank to sour. This souring process allowed the seed to be easily separated from the pulp, making washing the seed easier.

On mornings during melon season in Deerfield, the road would be lined with as many as 25 to 50 wagons loaded with barrels of melon on their way to the Arkansas River to wash seeds. After the washing process, seeds were placed on screened wire frames to dry. The frames were several feet off the ground allowing air to circulate and dry the seeds. Once dried, the seeds were ran through a fan mill to clean them from any foreign substance that might remain on them. The next step was to sack the seed for shipping.

In May of 1896, local papers reported that several farmers had filed suit against D.M. Ferry & Co. After receiving all of the previous year’s crop, Ferry & Co. claimed the seed was worthless and refused to pay the contract price. The farmers, in desperate need of their money, decided to do some investigating of their own and sent a seed buyer back to the company to buy a bunch of seed. George H. Tate of Lakin was chosen to do the job. On Tate’s arrival in Detroit, he made known his wants, stating that he would like to buy a large amount of seed grown in Western Kansas, preferably Kearny County. The seed company told Tate they had just what he wanted, the germination was near perfect and grown in Kearny County. He purchased seed and returned with the evidence in hand. In December that year, the Index reported that all the court cases against D.M. Ferry & Co. had been tried and that the farmers had won every time.

In 1909, 50,000 pounds of melon seed valued at 18¢ per pound were shipped from Lakin. One year later, the price had risen to 20¢ per pound. In 1910, William Logan’s Arkansas Valley Seed House was doing so much business that it had to move to a larger location. According to the Advocate, “the three establishments dealing in seeds and grain have had to enlarge their capacity every year for three years past.”

Although sugar beets soon surpassed melons as the main money crop grown in the area, the Advocate reported in 1920 that big, fine watermelons were being brought to town daily by the growers who found a ready sale for them. In the 29th Biennial Report of the State Board of Agriculture, G.W. Pepoon who lived on the South Side reported that melons in irrigated fields yielded 300 pounds of seed per acre in the early 30s. Both melons and sugar beets took a large amount of water to grow and eventually lost their dominance to feed and grain crops.

SOURCES: 29th Biennial Report of the Kansas State Board of Agriculture; Kansas State Historical Society; History of Kearny County Vol. I; History of Farming in Kearny County by Joyce Kopfman; and archives of The Advocate, Lakin Index and Garden City Sentinel.