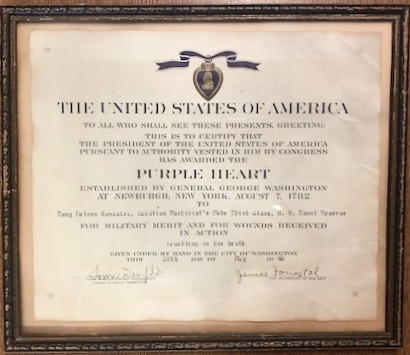

Tony was awarded the Air Medal for distinguishing himself by meritorious acts and demonstrating heroism while participating in flight operations, and in May of 1946, he was honored with the Purple Heart for military merit and for wounds received in action which resulted in his death. In 1950, Tony’s parents accepted his Distinguished Flying Cross medal in a ceremony at the Veterans Memorial Building. The honor was bestowed for Tony’s heroism and extraordinary achievement as an air-crewman in Patrol Bombing Squadron 101 during operations against enemy Japanese forces from June 1 to October 23, 1944. “Gonzalez rendered invaluable assistance to his pilot in carrying out hazardous long-range attacks against hostile planes, shipping and ground installation in the face of anti-aircraft fire and aerial opposition…Gonzales, by his skill and courageous devotion to duty throughout this period, upheld the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service. He gallantly gave his life for his country.”

Tony was awarded the Air Medal for distinguishing himself by meritorious acts and demonstrating heroism while participating in flight operations, and in May of 1946, he was honored with the Purple Heart for military merit and for wounds received in action which resulted in his death. In 1950, Tony’s parents accepted his Distinguished Flying Cross medal in a ceremony at the Veterans Memorial Building. The honor was bestowed for Tony’s heroism and extraordinary achievement as an air-crewman in Patrol Bombing Squadron 101 during operations against enemy Japanese forces from June 1 to October 23, 1944. “Gonzalez rendered invaluable assistance to his pilot in carrying out hazardous long-range attacks against hostile planes, shipping and ground installation in the face of anti-aircraft fire and aerial opposition…Gonzales, by his skill and courageous devotion to duty throughout this period, upheld the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service. He gallantly gave his life for his country.”

Discussion had begun a year earlier regarding the establishment of a veterans memorial. Olive Beaty made a generous donation to the Veterans Memorial Building Board, and after looking into the expense of erecting a memorial in front of the building, the board opted to get a tank, cannon or something else to honor the veterans. The project was turned over to the county commissioners who in turn appointed Paul Hendrix to oversee it. Hendrix drafted a letter to the U.S. Army Tank-Automotive and Armaments Command in Warren, Michigan and received word on September 28, 2001 that a tank was available at Fort Riley. First, the tank had to be demilitarized by the MATES at the base. On February 7, 2002, SFC Greg Verdoorn of Army Detachment 1, 443rd Transportation Company out of Dodge City received the release notice on the M60A43, and on February 15, the unit went to Fort Riley to load the tank and returned to Dodge City that night. On February 16, the unit left Dodge at 8 a.m. and entered Main Street in Lakin just before 10 a.m. Three U.S. Army vehicles and seven soldiers blocked off the street and had the tank unloaded and situated on a recently poured concrete pad before noon.

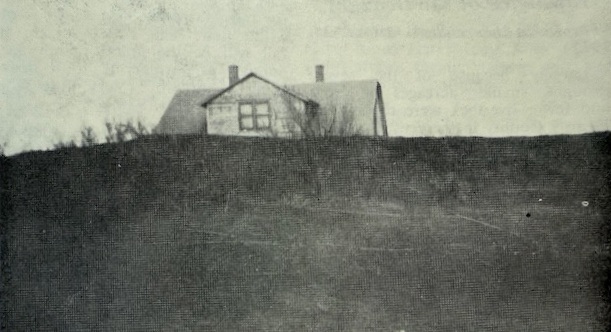

We are recognizing Mother’s Day and Lakin High School’s upcoming commencement with a history lesson about a local matriarch who was also the first graduate at Lakin. Lenora (Lena) Boylan was born in June of 1872 at Belle Plaine, Minnesota and moved to Lakin in 1875. The Boylan clan consisting of Lena, her parents, A.B. and Castella Boylan, and her younger brother, Bradner, was the second family of permanent settlers in the community. An older sibling, Hannah, had died at Sioux City, Iowa, in 1873 after being struck by a wheel that came off a passing train. The three-year-old was standing on a railroad platform when the tragedy occurred.

The Boylans were the first to live in the large white house which is now part of the Kearny County Museum complex. One of the first memories that Lena had about their new home was her father waking her up at dawn one morning so that she might see a buffalo eating from the haystack in their back yard. It was in that same back yard, while sitting on railroad ties that had been placed on end to form a fence, that she and her brother watched one of the first cattle roundups. The cattle, eight and ten abreast, started coming by in a steady stream during the early afternoon hours. By 10:30 that night, all the cattle had been driven across the river where they were cut out of the herd by their various owners.

Lena spent most of her childhood following her father around on horseback. An expert horseman, A.B. had come to Lakin as railroad agent but later took up farming, ranching, and the capturing and training of wild horses. One evening when father and daughter were in a spring wagon returning to Lakin from a day’s work north of town, they came across a buffalo on the trail. With patience and careful handling of the horses, they were able to drive the animal into town. A favorite past time of Lena’s was to pack a lunch, saddle her horse and ride out to a draw about 12 or 13 miles west of Lakin. She would sit there under two little trees to eat her lunch and then return home.

Lena’s formal education began when her mother purchased an empty store building for a school, and Amy Loucks began teaching a small group of local children there. When the 1886 school was built, A.B. Boylan was the first director of the school board. Lena completed the required two-year course for the high school and became the first ever graduate and only graduate in 1890. On Decoration Day, a starched and ruffled Lena delivered her commencement address on “National Cemeteries,” and she attended every alumni banquet until her health prevented her from doing so.

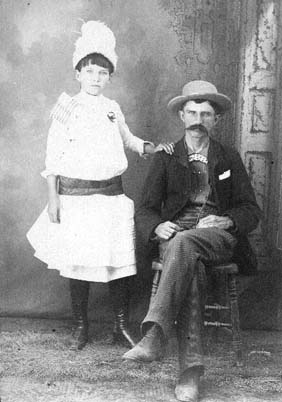

In June of 1891, Lena, her mother and brother left Lakin for Nepesta, Colorado where A.B. Boylan was employed as a Santa Fe agent, and in 1894, Lena married George Tate Jr. at Monument. Familiarly known as Harry, Tate had come to Lakin in the spring of 1885 with his father, George H. Tate Sr., who established a general hardware and mercantile business here. The newlyweds returned to Lakin, and Harry eventually took over managing his father’s store and was involved with other business ventures as well as the development of the community. About 1916, work was begun on a fine home on the northwest end of Lakin’s Main Street for Harry, Lena and their five children – James Noell, Victor, Cecil, Roland and Susannah (Florence Fletcher). This is now the residence of Lena and Harry’s great granddaughter Tammy Tate Meisel and her husband, Greg.

Over the years, Harry and Lena acquired quarters of land in Grant, Kearny and Hamilton Counties. They became ranchers in 1927, buying an 11,000-acre spread south of the river between Coolidge and Syracuse. This enabled them to lock up two large acreages and some other adjacent quarters to make quite a nice ranch suitable for summer and winter pasture. They stocked this first with cattle, then with work horses and brood mares, then started raising mule colts.

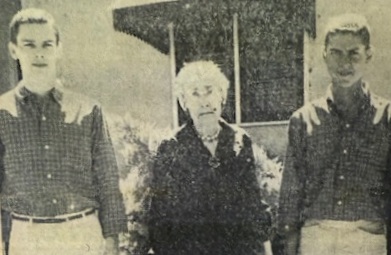

Lena dedicated her life to her family and her community. She was the local chairman of the Red Cross for 13 years, served on the school board, and was the first president of the American Legion Auxiliary. She was also an Old Settlers Association president, and Mrs. Tate served as county chair for the Women’s Council of Defense during the first world war. She held membership in the Lakin Literary Society, Lakin Woman’s Club, Women’s Missionary Society, Womens Christian Temperance Union, Kearny County Historical Society, PEO Chapter F.Q., Mus-Art Club, Lakin Book Club, Farm Bureau, Garden City’s St. Thomas Episcopal Church, and Order of Eastern Star where she served as Worthy Grand Matron and belonged to the Past Matrons’ Club.

Lena lived through drought, dust storms, blizzards, plagues, prairie fires, two world wars, the Great Depression, the development of the automobile, and countless other technical advancements. She witnessed firsthand the evolution of Southwest Kansas from open, rolling prairies filled with buffalo and wild horses to bountiful fields and bustling communities.

“A lot of the old timers like to look back and call them the good, old days, but I don’t know. I believe I’ll take electricity and gas with mine,” she said with a smile in a 1949 interview for the Garden City Daily Telegram. Lenora Victoria Boylan Tate died September 21, 1970, at Lakin. Her side saddle is one of the many treasures on display at the Kearny County Museum.

SOURCES: “Pioneering Tate Family Celebrates 100 Years In Kearny County” by Florence Tate Fletcher; Diggin’ Up Bones by Betty Barnes; History of Kearny County Vol. 1 & 2; The Boylan Web Portal; Ancestry.com; archives of Kearny County Advocate, The Lakin Independent, and Garden City Daily; and Museum archives.

First Kansas Governor Dr. Charles Robinson and his wife, Sara, will make an appearance at the Kearny County Historical Society’s Annual Meeting on May 3. Portrayed by Steve and Suzanne Germes of Topeka, the presentation is guaranteed to be both educational and entertaining. The public is invited to attend the event which also includes a meal and short business meeting. There is no charge, but reservations are required. To make yours, call the Museum at 620-355-7448 by 4 p.m. on Thursday, April 24.

This story about a 1930s dirt storm was written by the late Cora Rardon Holt and appeared in Volume II of the History of Kearny County.

I woke up one Tuesday morning and the smell which confronted me told me what to expect. A musty odor, that was disgustingly familiar, was the immediate explanation for the dim, strangely-colored half-light, that would be with us for some time. Outside the wind was howling and I knew we were having another duster. What I didn’t know was that it would be Friday morning before the air would again be clean and pure.

Sitting up in bed to turn on the light, I noticed the white print of my head on the pillowcase – everywhere else it had taken on a gray-brown color. Everything in the room was covered with a layer of tan silt. The curtains looked like they had been dipped in it. My bedroom slippers had to be emptied before I could put my feet into them. I had forgotten to turn them upside down the night before, a precautionary measure I had learned from past experience.

We lived in a sturdily-built stucco house with a living room extending the length of one side – 30 feet. As I came into this room, the light at the opposite end glowed like a fuzzy ball suspended in a thick haze, which made everything appear indistinct and far away. I looked down at the window sill, which was filling up with dirt, and a tiny landslide started and trickled down to the floor. Outside the window there seemed to be a wall; visibility was zero. This wall enveloped us as if we were contained in a capsule and, for days, changed only in color. If it took on a reddish-brown hue, we guessed New Mexico was going over; if it lightened to a dirty white, it might be Oklahoma; but always it would be black again, just like night.

Time hung heavy on our hands as the day progressed and eating posed a real problem. We learned to either gulp something like cereal and milk quickly under a newspaper tent, or to take our plates to the stove, ladle directly from a covered pan, and eat standing. Even then my teeth always ground particles of dirt and seemed to be coated with a layer of grime. My nose was full of it, like I had rooted in the ground. My face and skin were always gritty, and to scratch in my ear made a magnified, grating sound. Worse than all this to me, was the grit on everything I touched. It was a sandpaper effect that took the fun out of much we could have done to make the time pass more quickly – games for instance. We worked countless crossword puzzles from a stack of old Kansas City papers; we watched the changing colors at the window and a pile of dirt grow under a keyhole; and we scooped paths from room to room using a dustpan. Real cleaning of house or ourselves was an absolutely futile activity. But, perhaps, the most unbearable experience of all came at the end of the monotonous day when we had to go to sleep in a dust-laden bed.

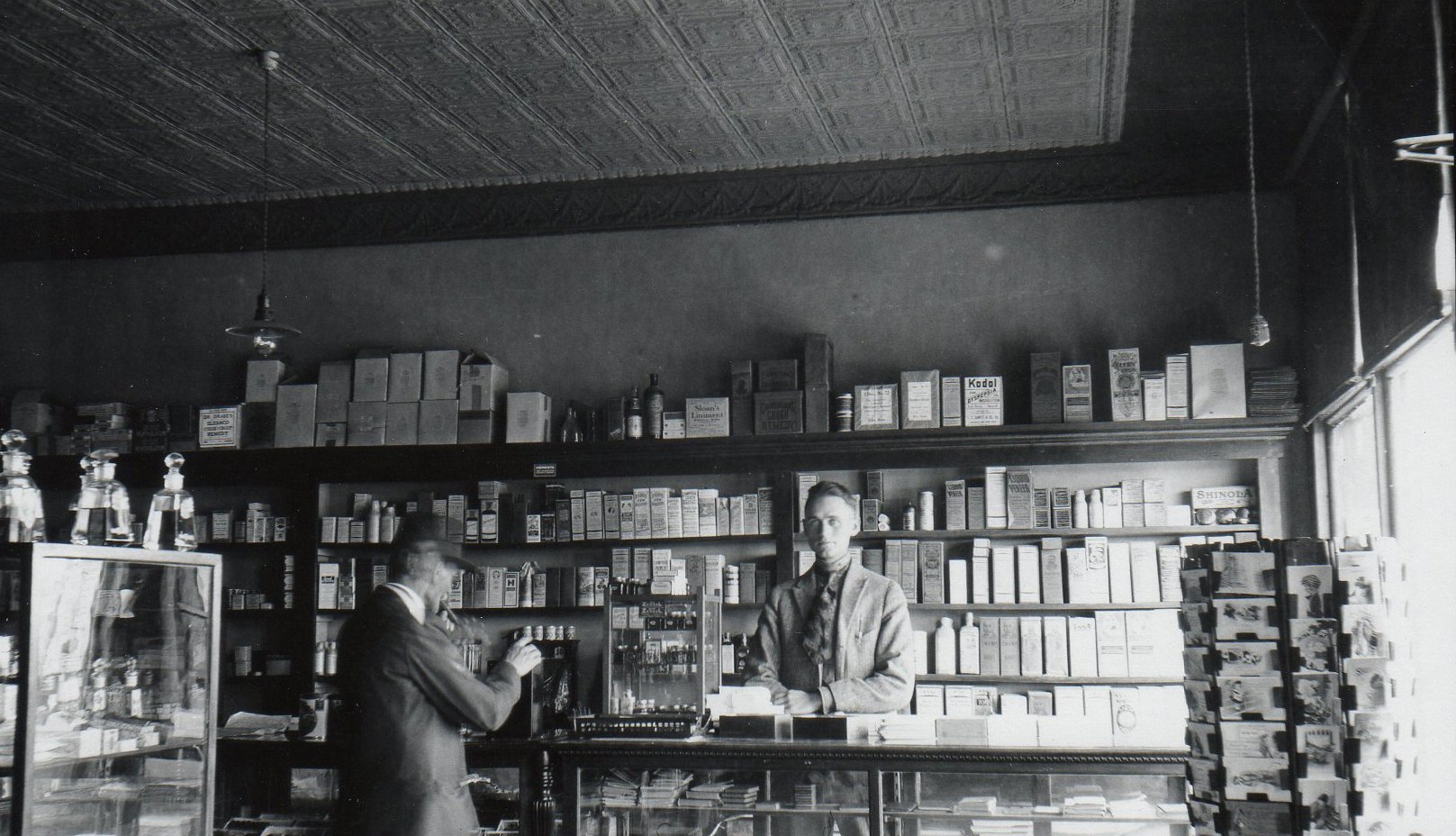

We lived two miles from town at that time and owned the drugstore. My father went the distance each morning to be there in case someone needed medicine. He would don his homemade gauze face-mask and top that with a narrow-brimmed Stetson hat, which was his trademark, before he braved the elements. When he returned, he was even dirtier than the rest of the family. He was our only link with the outside world. There was no telephone service, no trains ran, and the highways in all directions were blocked. People from eighteen states were marooned in our little town during this blackout.

We had some day-long dirt storms again two decades later and newspapers coined the phrase, “Filthy Fifties,” but we old-timers sort of chuckled and said, “They don’t hold a candle to the ‘Dirty Thirties.’”

April 14th marks the 90th anniversary of Black Sunday, the day that the Great Plains was struck by what was considered to be the worst dust storm of them all. It wasn’t the first dust storm that Kansans endured during the Dirty 30s, and it definitely wasn’t the last. Drought had ravaged the plains states since 1931. Little to no rain – together with poor soil conservation and overplowing – meant that when the typical high winds that are common in this area blew, they blew dirt. Eyewitnesses said one could tell where the dust storms originated by the color of the dust: black soil came from Kansas, red soil from Oklahoma and gray from Colorado and New Mexico. In all, it is estimated that 350 million tons of soil from Kansas, Texas and Oklahoma were deposited in eastern states.

Black Sunday started out mildly enough. The dust had settled out of the air, and it was a quiet afternoon with few clouds in the sky. Working on a farm south of Kendall, Howard Zook saw the rumbling wall of dirt approaching. “It just looked like a big solid bank rolling in,” said Zook. “When it hit the sun, the sun disappeared, and we beat it into the house. We stood there leaning against the wall. The only way you knew where people were was by feel. We could reach out and hit ‘em. You couldn’t see ‘em a foot away from ya. The dirt was just that thick.”

John Grusing and his sons were working a mile northwest of their home in northern Kearny County when the storm hit. “We couldn’t see the road or anything at all. We didn’t know where to turn south or where we were after we turned south. Then we came to a fence,” he recalled. “I knew my own fences so we felt of the wires … knowing the fence west of the house was a two-wire and the fence north was a three-wire, I could tell where we were. Every joint in the fence sparked with electricity. The fence was a three-wire fence and by that we knew how to follow it to the house. There were lights on in the house, but we couldn’t see the lights from the windows as the dust was so dense. But we knew now where we were and finally felt our way to the door.”

The Lakin Independent reported, “A spectacular dust storm came over us Sunday afternoon from the north, and within two minutes the country was plunged into dense midnight darkness. It was impossible to see a hand before your face or to drive a car into the garage. Ernest White was out on horseback and unable to see the horse he was riding. After a half hour the atmosphere cleared a little, but the storm kept on, and lamps were needed the rest of the day.”

Hannah Rosebrook lived in the Fairview Community near the Wichita County line and wrote a weekly column for The Independent. In the April 19th issue, she said, “Still we are fighting dirt. Not a minute’s let-up since Sunday at 1:00 p.m.”

The Black Sunday storm was estimated to be 500 to 600 feet in height, moved at a rate of 50 to 60 mph, and covered approximately 800 miles. Some wind gusts reached up to 100 miles per hour. The temperature dropped 25 degrees per hour, and more than 300,000 tons of soil blew away. That is twice as much dirt as was dug out of the Panama Canal. It was after the Black Sunday storm that Robert Geiger, an Associated Press reporter, coined the phrase, “Dust Bowl.”

Meteorologists rate the Dust Bowl as the #1 weather event of the 20th Century. The first notable dust storm with winds reaching 60 mph was documented on Sept. 14, 1931, and the weather bureau reported 14 bad dust storms the following year. By 1933, the number had increased to 38. During March and April of 1935, about 4.7 tons of dust per acre fell on western Kansas during each dirt blizzard. In 1937, a high of 72 storms marked a peak in the Dust Bowl era. Rosebrook reported not seeing the sun from Saturday until Wednesday noon during one of the severest periods in February of 1937.

The Independent described the dirt as, “fine, penetrating dust that fills the air like driven snow; stifling, blinding, it comes in through every crack and crevice and fills the whole house with silt, and piles up in drifts beside buildings and in sheltered places as it blows and swirls through town and country.” Those who inhaled the dust suffered coughing spasms, shortness of breath, asthma, bronchitis and influenza. Hundreds died from dust pneumonia, also known as the ‘brown plague.’ Infants, children and the elderly were especially susceptible. The Red Cross set up emergency hospitals in the Dust Bowl states and handed out 17,000 gauze masks, but it could take less than an hour exposure outside to darken one of the masks.

Livestock also suffered. Lack of feed reduced them to weakened conditions, and many were unable to stand the black blizzards. Some drifted with the storms and starved before being found while others smothered. Dust buried buildings, shrubs, farm fences and machinery. Tourists were unable to further their journeys and took refuge wherever they could. Trains were stopped in their tracks, and dust storm “holidays” were declared for students.

Complicated by the Great Depression, overpopulation of jackrabbits and hordes of grasshoppers, conditions continued to deteriorate on the Great Plains. By 1940, 2.5 million people had left the area, at least 300,000 traveling to California in what was considered the largest single migration in U.S. history. Approximately 250,000 boys and girls became hobos.

Several national programs such as the Civilian Conservation Corps and Soil Conservation Service were born to combat the effects of not only the crippling dust storms but the drowning economy as well. Men were put back to work through programs like the Works Progress Administration and Public Works Administration which led to the construction of the Kendall bridge, Menno Community building and the Kearny County courthouse. Still others were employed on conservation projects like planting tree rows or shelterbelts. Causes for the Dust Bowl were carefully studied, and new agricultural methods were encouraged such as terracing, contour farming, crop rotation, strip farming and planting ground cover.

The drought and its associated impacts finally began to subside in the spring of 1938, and by 1941, most areas of the country were receiving near-normal rainfalls. These rains, along with the outbreak of World War II, alleviated many of the domestic economic problems of the preceding decade. Drought returned in the 1950s, and from 1954-1957, twice as many acres in the Great Plains were damaged annually by wind erosion as from 1934-1937. Improved farming techniques and equipment, soil conservation, and irrigation saved the area and its people from a repeat of the Dirty ‘30s.

SOURCES: National Weather Service; National Drought Mitigation Center; Kinsley Public Library; “Dust Bowl” by Donald Worster; “Ethnic Heritage Studies: The Fairview News”; History of Kearny County Vol. II; Archives of the Lakin Independent; Hutchinson News, and Southwest Kansas Senior Beacon; and Museum archives.

Fortitude was a standard requirement for one-room school teachers in Kansas during the late 1800s and early 1900s. Instructors were often female, unmarried, and in many cases, only a year older than some of the students in their classroom. Challenged with limited resources and rudimentary rooms and supplies, rural school marms generally had minimal teacher training too. Most were recent graduates of normal schools which in this area of Kansas amounted to a one-week crash course to prepare them for the classroom. These young women were not only responsible for teaching all grades in a single room, but also performed custodial duties, served as counselors, and administered first aid. They were charged with maintaining the classroom, hauling water for drinking and washing, and were responsible for hauling wood (or cow chips) and kindling the fire. Teachers had to be at school early to get the wood-burning stoves started to warm up their rooms before the arrival of their students.

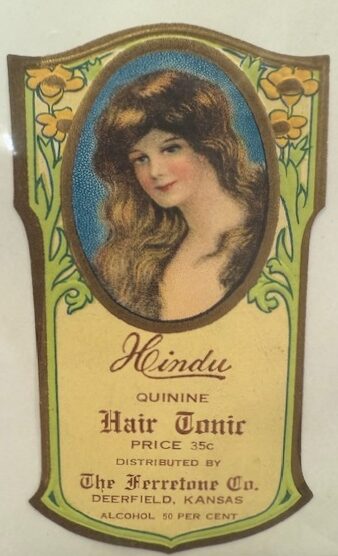

Veturia E. Boyd taught at the Deerfield school in the winter of 1887-1888. Miss Boyd walked back and forth to her school each day as she boarded with Ada Oliver, a single woman who lived in a dugout three-quarters of a mile north of the schoolhouse. The school board told the young teacher that if a blizzard ever arrived to never send the children home but to keep them at the schoolhouse until help arrived. On December 19, 1887, a blizzard arrived during school hours and unleashed its fury. Somehow, Miss Boyd got all the school children dismissed safely, and she started for Miss Oliver’s place in the middle of the afternoon. Starting was about all she got done. For nearly two hours, she walked around in circles and asked the good Lord for help.

She eventually stumbled upon the dugout door of a young bachelor named Dayton Loucks. Hearing a loud noise and wondering what it was, Loucks pried opened his door and in dropped Miss Boyd. Both were quite surprised to see one another; nonetheless, Miss Boyd was thankful to have found shelter. She was a shy and modest woman and spent the night in her wet clothes, sitting in front of the fire for warmth and to dry her clothing. Outside, the blizzard howled on, but the next morning dawned bright and clear. Miss Boyd thanked Loucks and walked a quarter mile south to the Neil Beckett farmstead where Mrs. Beckett gave her some breakfast and fixed her a lunch to take to school for her dinner. Miss Oliver, worrying that Miss Boyd had not made it home the night before, went to the schoolhouse and found the educator there getting ready for her students and another day of teaching.

Boyd’s story is not atypical of the young women who taught in rural schools. Many a night was spent inside a schoolhouse because of severe weather, sometimes with charge of students and little (if any) food. Occasionally these young female teachers were left in their schools to battle the forces of nature all alone. Their grit was unmatched.

Miss Boyd was born in 1862 in Indiana and came to Kearny County in the spring of 1886 to take a claim near Lakin. She also taught at Lakin and in Finney County before she returned to the Midwest where she taught in a Chicago suburb. She later became a doctor of osteopathy and often led five-mile nature walks and hikes in the Chicago area. Miss Boyd never married, and she returned to Lakin on more than one occasion to visit friends she had made during her time here. She died in 1935 at Chicago.

Kearny County Museum tips our hat to Veturia Boyd and other teachers like her who left their mark on history and in the hearts of the students they taught. And that’s a rap for Women’s History Month! We hope you’ve enjoyed the stories we’ve shared this month about some of the remarkable women of Kearny County, Kansas!

SOURCES: History of Kearny County, Vol. I; archives of The Lakin Index, Kearny County Advocate, Garden City Herald, Chicago Tribune, and Warrick Enquirer; ancestry.com and findagrave.