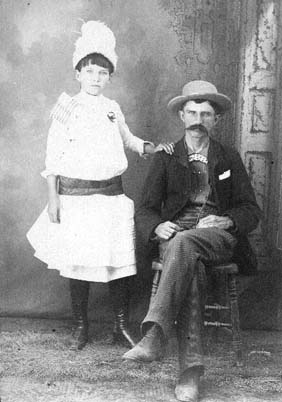

We are recognizing Mother’s Day and Lakin High School’s upcoming commencement with a history lesson about a local matriarch who was also the first graduate at Lakin. Lenora (Lena) Boylan was born in June of 1872 at Belle Plaine, Minnesota and moved to Lakin in 1875. The Boylan clan consisting of Lena, her parents, A.B. and Castella Boylan, and her younger brother, Bradner, was the second family of permanent settlers in the community. An older sibling, Hannah, had died at Sioux City, Iowa, in 1873 after being struck by a wheel that came off a passing train. The three-year-old was standing on a railroad platform when the tragedy occurred.

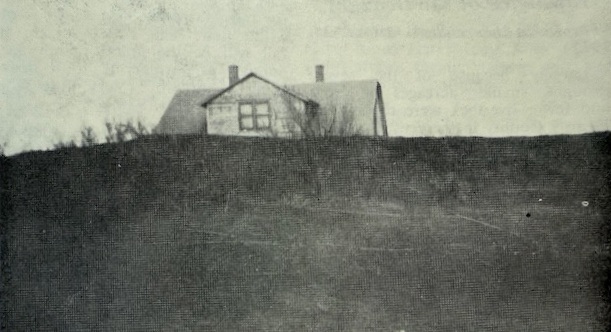

The Boylans were the first to live in the large white house which is now part of the Kearny County Museum complex. One of the first memories that Lena had about their new home was her father waking her up at dawn one morning so that she might see a buffalo eating from the haystack in their back yard. It was in that same back yard, while sitting on railroad ties that had been placed on end to form a fence, that she and her brother watched one of the first cattle roundups. The cattle, eight and ten abreast, started coming by in a steady stream during the early afternoon hours. By 10:30 that night, all the cattle had been driven across the river where they were cut out of the herd by their various owners.

Lena spent most of her childhood following her father around on horseback. An expert horseman, A.B. had come to Lakin as railroad agent but later took up farming, ranching, and the capturing and training of wild horses. One evening when father and daughter were in a spring wagon returning to Lakin from a day’s work north of town, they came across a buffalo on the trail. With patience and careful handling of the horses, they were able to drive the animal into town. A favorite past time of Lena’s was to pack a lunch, saddle her horse and ride out to a draw about 12 or 13 miles west of Lakin. She would sit there under two little trees to eat her lunch and then return home.

Lena’s formal education began when her mother purchased an empty store building for a school, and Amy Loucks began teaching a small group of local children there. When the 1886 school was built, A.B. Boylan was the first director of the school board. Lena completed the required two-year course for the high school and became the first ever graduate and only graduate in 1890. On Decoration Day, a starched and ruffled Lena delivered her commencement address on “National Cemeteries,” and she attended every alumni banquet until her health prevented her from doing so.

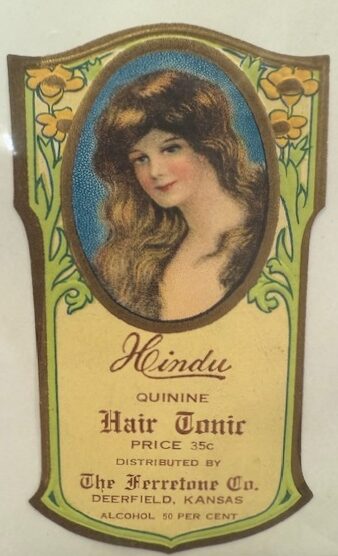

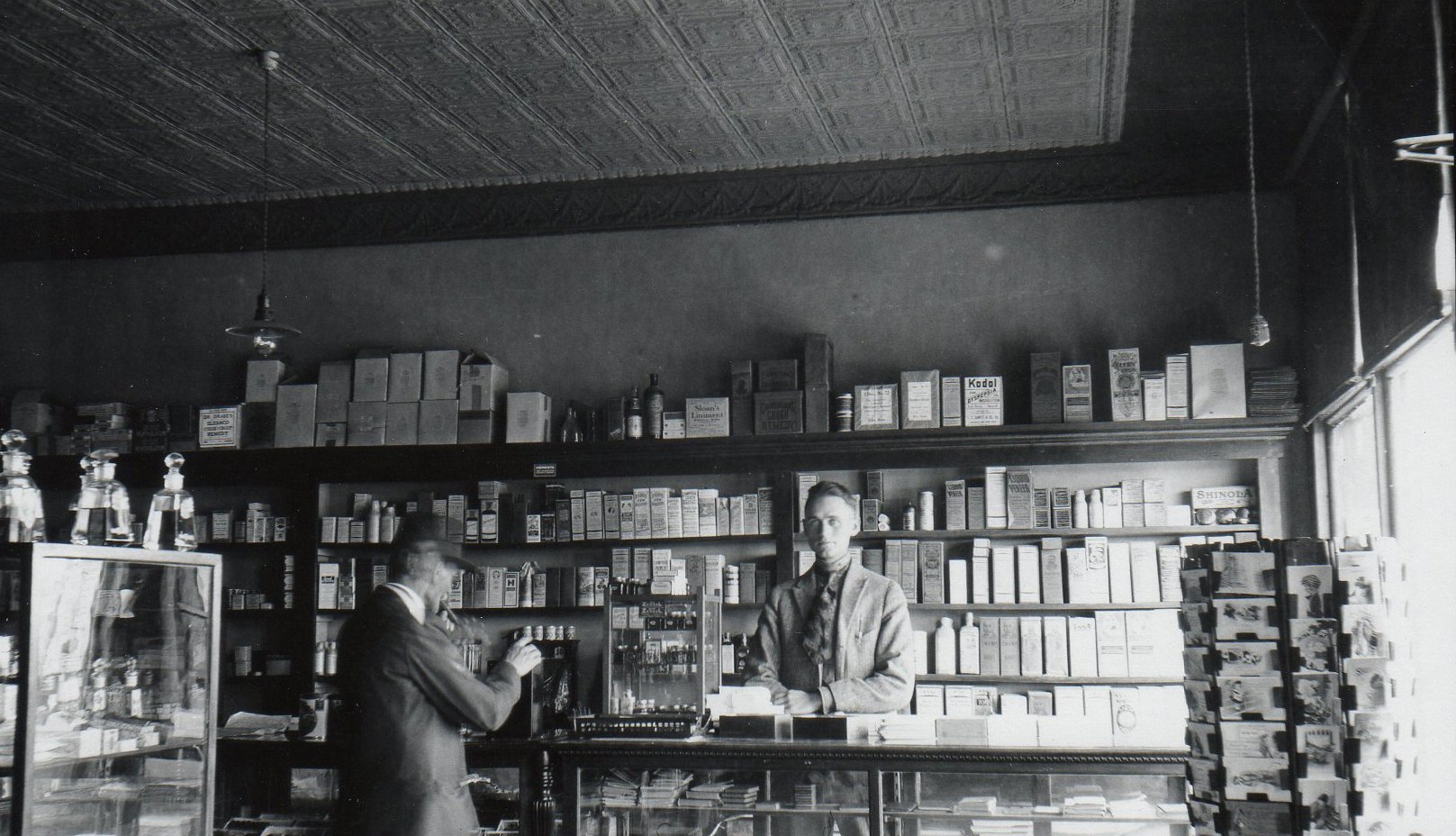

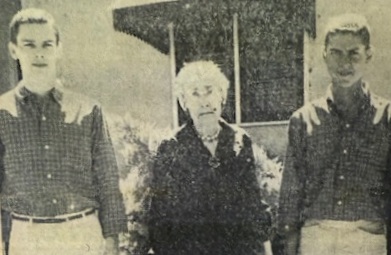

In June of 1891, Lena, her mother and brother left Lakin for Nepesta, Colorado where A.B. Boylan was employed as a Santa Fe agent, and in 1894, Lena married George Tate Jr. at Monument. Familiarly known as Harry, Tate had come to Lakin in the spring of 1885 with his father, George H. Tate Sr., who established a general hardware and mercantile business here. The newlyweds returned to Lakin, and Harry eventually took over managing his father’s store and was involved with other business ventures as well as the development of the community. About 1916, work was begun on a fine home on the northwest end of Lakin’s Main Street for Harry, Lena and their five children – James Noell, Victor, Cecil, Roland and Susannah (Florence Fletcher). This is now the residence of Lena and Harry’s great granddaughter Tammy Tate Meisel and her husband, Greg.

Over the years, Harry and Lena acquired quarters of land in Grant, Kearny and Hamilton Counties. They became ranchers in 1927, buying an 11,000-acre spread south of the river between Coolidge and Syracuse. This enabled them to lock up two large acreages and some other adjacent quarters to make quite a nice ranch suitable for summer and winter pasture. They stocked this first with cattle, then with work horses and brood mares, then started raising mule colts.

Lena dedicated her life to her family and her community. She was the local chairman of the Red Cross for 13 years, served on the school board, and was the first president of the American Legion Auxiliary. She was also an Old Settlers Association president, and Mrs. Tate served as county chair for the Women’s Council of Defense during the first world war. She held membership in the Lakin Literary Society, Lakin Woman’s Club, Women’s Missionary Society, Womens Christian Temperance Union, Kearny County Historical Society, PEO Chapter F.Q., Mus-Art Club, Lakin Book Club, Farm Bureau, Garden City’s St. Thomas Episcopal Church, and Order of Eastern Star where she served as Worthy Grand Matron and belonged to the Past Matrons’ Club.

Lena lived through drought, dust storms, blizzards, plagues, prairie fires, two world wars, the Great Depression, the development of the automobile, and countless other technical advancements. She witnessed firsthand the evolution of Southwest Kansas from open, rolling prairies filled with buffalo and wild horses to bountiful fields and bustling communities.

“A lot of the old timers like to look back and call them the good, old days, but I don’t know. I believe I’ll take electricity and gas with mine,” she said with a smile in a 1949 interview for the Garden City Daily Telegram. Lenora Victoria Boylan Tate died September 21, 1970, at Lakin. Her side saddle is one of the many treasures on display at the Kearny County Museum.

SOURCES: “Pioneering Tate Family Celebrates 100 Years In Kearny County” by Florence Tate Fletcher; Diggin’ Up Bones by Betty Barnes; History of Kearny County Vol. 1 & 2; The Boylan Web Portal; Ancestry.com; archives of Kearny County Advocate, The Lakin Independent, and Garden City Daily; and Museum archives.