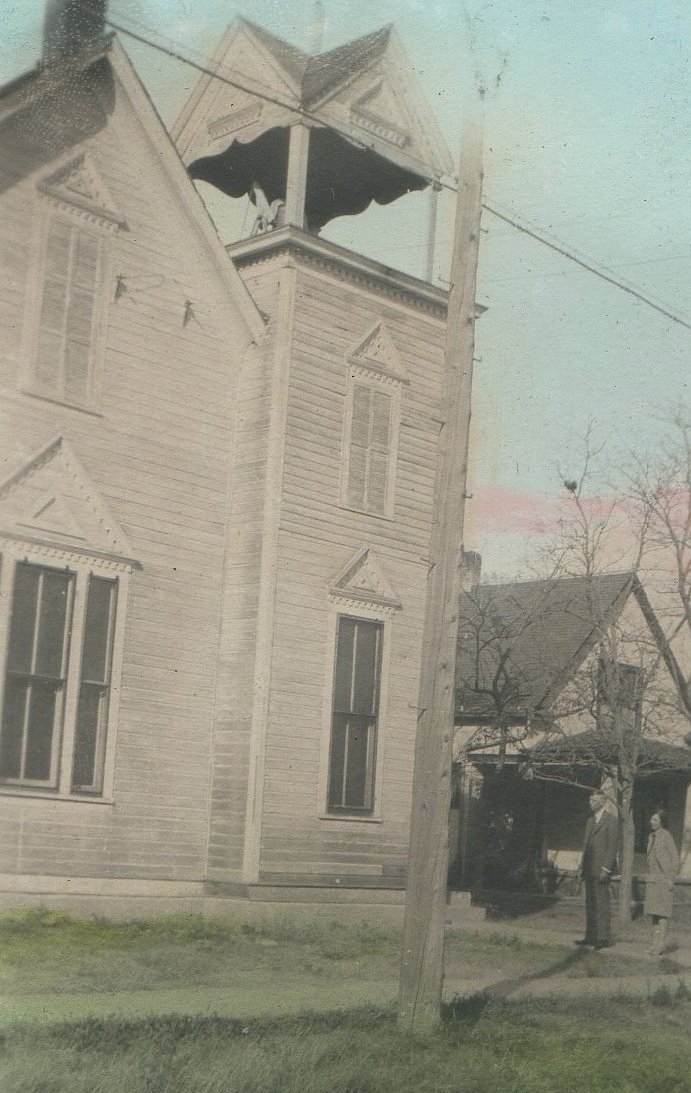

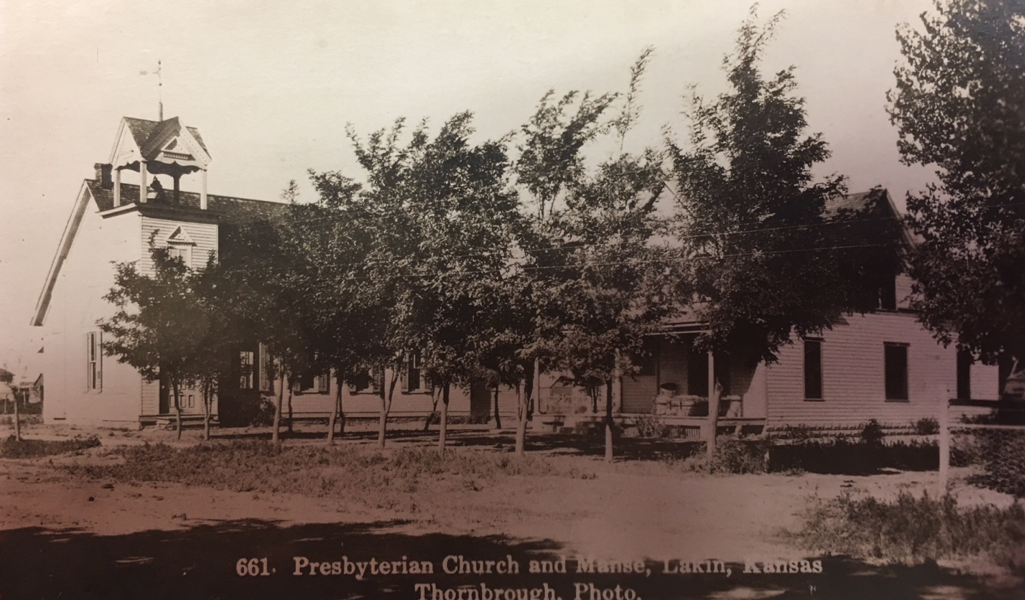

Dr. Browning of Garden City delivered a stirring sermon at the first services in the church on Thursday, July 11, 1895. This was the first segment of a four-day grand dedication service which included sermons by C.E. Williams, pastor of the local Methodist congregation, and ministers from Wichita and Hutchinson. On Sunday, July 14, the church building was crowded to full capacity with many friends from Hartland and Deerfield in attendance. Dr. S.B. Fleming of Wichita surprised the crowd when he announced that $450 was to be raised before the dedication exercises could be completed. In less than 30 minutes, $460 had been given either in cash or by promise.

Dr. Browning of Garden City delivered a stirring sermon at the first services in the church on Thursday, July 11, 1895. This was the first segment of a four-day grand dedication service which included sermons by C.E. Williams, pastor of the local Methodist congregation, and ministers from Wichita and Hutchinson. On Sunday, July 14, the church building was crowded to full capacity with many friends from Hartland and Deerfield in attendance. Dr. S.B. Fleming of Wichita surprised the crowd when he announced that $450 was to be raised before the dedication exercises could be completed. In less than 30 minutes, $460 had been given either in cash or by promise.

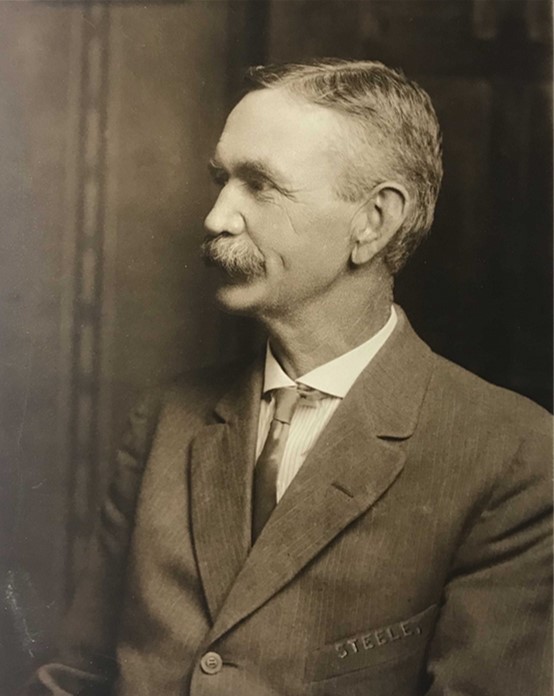

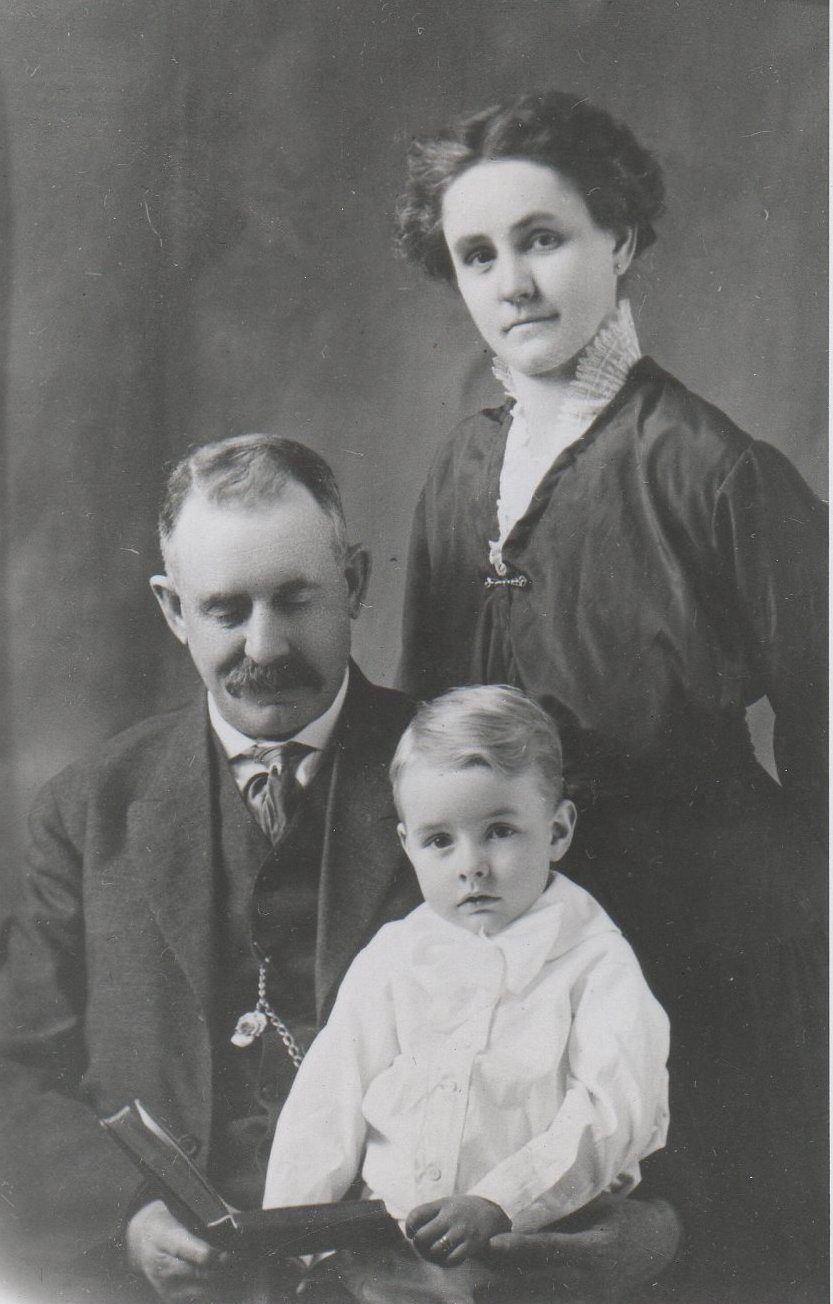

David Harold Browne came to Kearny County to work as a clerk in the railroad eating house. The oldest of three boys born to Charles Browne and Helen Potter Browne, Harry was born at Cowansville, Canada on April 18, 1859. While growing up, he spent much of his leisure time ice-skating and attending “sugar-off” parties, a French-Canadian tradition that brought friends and families together to enjoy the sugar high that comes from boiling maple sap into taffy. Harry’s father was a doctor, and Harry often helped in his office and rode with him to visit patients and help with emergencies. The knowledge of medicine which Harry gained in this way was most useful to him in later years as a pioneer in Western Kansas.

His father died five days before Harry’s seventeenth birthday, and his mother moved the family to Chicago, Illinois where her people lived. Harry had to quit school and go to work to help support his mother and brothers. His first position was as a clerk for a packing company, and in 1880, Harry joined his maternal uncle, Guy Potter, who was managing the eating house here. Shortly after Fred Harvey became the proprietor of the dining hall/hotel, the building was moved to Coolidge which became the division point of the Santa Fe Railroad. Harry remained here, and for a time, he joined Alonzo Boylan and Rolla Walter in catching and taming wild horses which they sold to cowboys and horse traders. After a time, Harry took a clerk position at John O’Loughlin’s general store.

While working for O’Loughlin, Harry met Maria Dillon, one of Lakin’s most popular young women. Born in New York City on June 17, 1866, Maria lost her mother as a small child and was educated in a convent in Montreal, Canada. She came to Kearny County in 1879 with her father, step-mother and younger siblings, and she made a name for herself as one of the best compositors in Kansas while working at the Lakin Herald where her father served as editor. Wearing a blue silk taffeta dress fashioned with a fitted basque and pleated bustle, Maria married Harry in an evening ceremony on April 7, 1886, at the dugout home of her brother in-law and sister, Alexander and Annie Cross. Three children were born to Harry and Maria: Helen Florence (Mr. J.H. Rardon), Charles Harold, and Hazel Louise (Mrs. F. Ivor Williams).

Harry was the first elected county clerk of Kearny County, and the Browne family moved eventually to Hartland and then back to Lakin when Lakin won the 1894 election. Harry recalled that one of the most dramatic events in his life was counting votes for the location of the county seat. Each town that had entered the race had the privilege of sending men to see that the votes were properly counted. Barney O’Connor was Lakin’s representative and stood over the election judges with six-shooter in hand, and Harry said he never expected to get out of the building without someone being killed. He was re-elected to the county clerk position several times, serving until 1896, and also worked as assistant cashier in the Kearny County Bank.

When Harry’s health failed, his doctor recommended a change of climate. Harry decided to buy a team and wagon and go overland to Colorado Springs, taking his herd of purebred jersey cattle and selling them along the way. One fine June morning in 1896, the Browne family stored all their worldly possessions in a covered wagon and started to Colorado. First was Maria with one of the girls in a top buggy drawn by a blaze-faced bay horse named Bally, then came the wagon to which were hitched two large gray mares with Harry as driver, and then the herd of cattle urged on by Doc Miller, the hired hand. Except for being awakened one night by water flooding their campground, the trip was uneventful. It took about a month to complete the journey and dispose of the cattle. At Colorado Springs, Harry engaged in the coal business with his friend, Frank Kelly, whom he had made acquaintances with earlier in life.

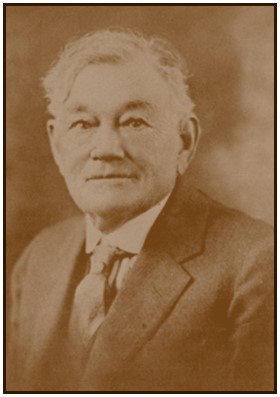

After three years and the death of Ben Bacon who was the cashier at Kearny County Bank, Harry was beckoned back to Lakin to fill Bacon’s shoes. Harry was always interested in everything for the advancement of his town and county and gave generously of his time to that end serving as a member of the board of education and on the city council. He was an ardent fisherman and lover of nature, and when worries and pressures of business weighed heavily upon him, he would spend the day fishing at Lake McKinney. Harry always came back with a cleared mind and refreshed body. He had the gift of being a good listener and gave to others a feeling of strength and confidence.

Harry maintained his position at the bank until his death on March 8, 1931. He had been in failing health for some time, but the trooper that he was, Harry continued working until three days before his death. He was loved and respected by all who knew him, and all the banks and business houses in Lakin closed during his funeral. Known as Gippy to his grandchildren, his granddaughter, Cora Rardon Holt, wrote of him, “I shall always remember his long fingered, iron strong hands. They revealed his character and always gave me a sense of comfort and security.”

Maria, or Gammy as she was known to her grandchildren, died on Oct. 18, 1948, as a result of shock caused by burns she received earlier that day. It was thought that her robe may have caught on fire as all three burners of her oil stove were lit, and coffee was boiling on the middle burner. Maria also was very much loved in the community, and she was remembered for the sunny disposition that characterized her her entire life. She had been a lifelong caregiver; first to her younger siblings, then to her own children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

SOURCES: Information provided by the late Hazel Browne Williams and Charles R. Browne, great grandson of D.H. and Maria Browne; History of Kearny County Vol. 1; Ancestry.com; museum archives, and archives of The Advocate and Lakin Independent.

The U.S. House of Representatives voted to admit Kansas as a state in April of 1860, but the Senate was under the influence of pro-slavery leaders and refused. The failure to admit Kansas became a national political issue. At the Republican’s national convention the following month, Abraham Lincoln was nominated as the Republican candidate for president. A strong proponent for Kansas, Honest Abe had visited the territory and spoke at several sites in December of 1859. When he won the presidency, news of his election caused 11 southern states to withdraw from the Union and set up a separate government. As each state withdrew, their senators and representatives resigned their seats in Congress, vastly reducing the number of those in the Senate who opposed Kansas’s admission. The Senate passed the Kansas Bill, and President Buchanan signed the bill officially admitting Kansas to the Union on January 29, 1861. While on his way to Washington for his inauguration in 1861, President-elect Lincoln had a stop off at Philadelphia’s Independence Hall where he hoisted the first United States flag bearing the Kansas star on February 22 (George Washington’s birthday).

The difficulties that Kansas faced in gaining statehood led John J. Ingalls, secretary of the first Kansas state senate, to suggest the state motto of “Ad Astra per Aspera” which is Latin for “To the Stars Through Difficulties.” The motto was placed at the top of the state seal, and below it 34 stars, representing Kansas as the 34th state to join the union, are boldly arranged. Pictured in the right-hand corner of the seal is a rising sun for the east. Commerce is represented on the seal by a river and a steamboat, and agriculture as the basis of Kansas’s future prosperity is represented by a settler’s cabin and a man plowing with a team of horses. Also depicted are a wagon headed west and pulled by oxen, as well as a herd of retreating buffalo being pursued by two Native Americans on horseback.

In 1903, the sunflower was adopted as the state flower by the Kansas Legislature, and on Kansas Day in 1925, the western meadowlark was announced as the state bird of Kansas. In an election coordinated by the Kansas Audubon Society, nearly 50,000 of 121,000 votes were cast by Kansas school children for the meadowlark; however, the Kansas Legislature did not officially make it the state bird until 1937. Adopted in 1927, the Kansas state flag was designed by Lincoln, Kansas seamstress Hazel Avery. The flag was modified in 1961 by adding the word, “Kansas,” in gold block letters below the seal.

The cottonwood was adopted as the state tree in 1937, and in 1947, “Home on the Range” became the official state song.” In his cabin on Beaver Creek near Smith Center in 1871 or 1872, Dr. Brewster Higley wrote the lyrics to the song which was originally entitled, “My Western Home.” Druggist Dan Kelly composed the music. In 1955, the American buffalo was named as the state animal, and the honey bee was adopted as the state insect in 1976. It was not until 1986 that the ornate box turtle was established as the state reptile. These are but a few of Kansas’s more well-known state symbols, but did you know that our state soil, established in 1990, is harney loam silt, , and the barred tiger salamander was named state amphibian in 1994? In 2010, little bluestem was named the state grass, and the tylosaurus and pteranodon became the state fossils in 2014. In 2018, limestone was established as the state rock, galena the state mineral, jelinite the state gemstone, and channel catfish the state fish. In 2019, chambourcin was named the state’s red wine grape while vignoles, the state white wine grape. In 2022, the sandhill plum was recognized as the state fruit, and silvisarus condravi, the woodland lizard that lived from the Early to Late Cretaceous Period, has been the state land fossil since 2023.

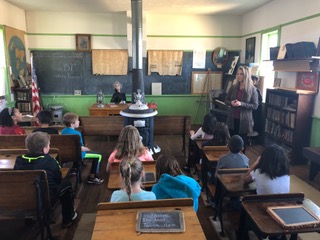

Alexander Le Grande Copley, a teacher in the Paola school system, is credited with the origination of Kansas Day. On January 29, 1877 after spending two weeks gathering information on the geography, history and resources of Kansas, Copley’s students presented their maps, drawings, songs and speeches to their community. The event was so well attended that there was not room for everyone in the small school. Copley later became the superintendent of Wichita schools and implemented Kansas Day there. Copley attended county teachers’ institutes and state teachers’ association meetings where he encouraged teachers to celebrate Kansas Day. In 1882, at the first meeting of the Northwestern Teachers Association, a decision was made to publish a small pamphlet which included information about Kansas, its songs and sample speeches suitable for the observance of Kansas Day. The 32-page booklet was simply called, “Kansas Day.” At the next State Teachers Association meeting in Topeka, every teacher took home one or more copies. For a short time, the booklet was used as a textbook in the state normal school at Emporia.

The popularity of Kansas Day continued to grow and is celebrated by teachers and students across the state. For the past several years, Lakin Grade School students have enjoyed Kansas Day tours at the museum where they learn about Kansas, the Santa Fe Trail, one-room schools, pioneer life and local history. Today, January 29, we welcome Lakin’s third graders and celebrate the 164th birthday of our grand state. Happy Birthday, Kansas!

KANSAS

Not for what she hath done for me,

Though it be great,

For what she is, her majesty,

I love my State.

Thomas Emmet Dewey

SOURCES: Sunflowers, A Book of Kansas Poems; The Story of Kansas by Bliss Isely and W.M. Richards; Kansas … Our State by Goebel, Heffelfinger and Gammon; Kansas State Historical Society, and Museum archives.

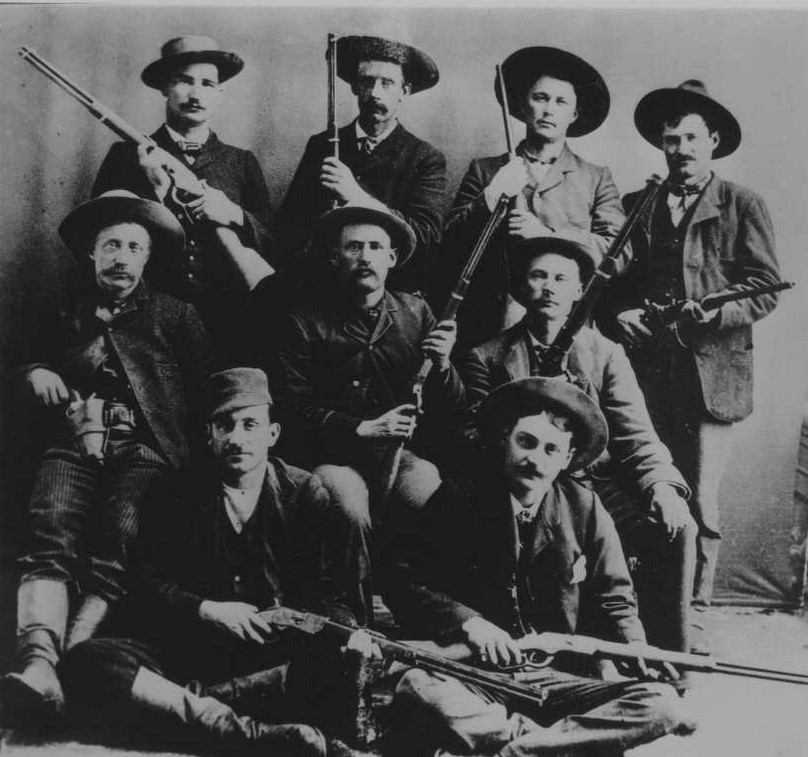

When Mike Fontenot takes the oath of office as the new Kearny County Sheriff on January 13, he will become the latest in a long and storied list of local lawmen dating back to the 1800s. John Henry Carter was the first man charged with keeping the peace in our area. He was appointed undersheriff of Kearny Township in 1879 when what is now Kearny County was part of Ford County. Southwest Kansas was considered part of the wild, wild west at that time, and Carter’s heroics are well documented.

In 1882, a lucrative reward was offered for the capture and conviction of Thomas Wooten (sp.) and James McCullom who had robbed and murdered a railroad section foreman near WaKeeney. After hearing that the fugitives had been seen in our neck of the woods, Carter guessed the duo was headed to Point of Rocks Ranch in the extreme southwest corner of the state. Carter secured a good horse and reached the area about nightfall but learned that no strangers had been seen there. He cautioned the ranch’s owner and cowboys to show no surprise nor suspicion if the men arrived later. After everyone had gone to their bunks, two men rode up on worn-out horses and asked to spend the night. They were given coffee and food and allowed to sleep in their blankets on the kitchen floor which was next to where Carter was to sleep. But Carter saw no sleep that night, remaining constantly alert for any movements from the suspected men.

At dawn, lawman Carter slipped his rifle over the kitchen window sill and made his way out of the house, walking through the area where the desperadoes were still wrapped in their blankets. Carter secured his rifle and went to a deep buffalo wallow between the house and where Wooten and McCollom’s horses were tied. The wallow afforded partial concealment to John. Wooten came out of the house and started for the horses, and when he was about 50 feet away, Carter shouted, “hands up.” Wooten swiftly pulled two revolvers out and sent bullets flying in Carter’s direction. Carter returned fire, missing with his first shot but hitting Wooten with his second which left a silver-dollar-sized hole in the man’s shoulder.

McCullom reached the scene, and seeing his compadre lying on the ground in great agony, fired several bullets at Carter. The shots missed the lawman but raised a cloud of dust. McCullom then rushed towards Carter before firing his last charge. Carter waited until McCollom was within such close range that his vision was clear, took aim and killed McCollom with one shot. Carter brought Wooten to Lakin where the killer’s wound was dressed. Trego County undersheriff Joseph Lucas came to Lakin and took custody of the prisoner, but Lucas was later assaulted at WaKeeney by a masked angry mob who took Wooten. Some accounts say the mob hung Wooten while others say he escaped; regardless, Carter was deprived of the very handsome reward despite a concerted effort to secure a special $1,000 appropriation from the Legislature for his bravery. One account claimed that Carter did receive $300 for his efforts.

In August of 1887 when talk was circulating in the area about the Governor appointing a temporary sheriff here, both Chantilly and Hartland endorsed Carter for the position. Nearly 500 voters signed a petition asking the Governor for Carter’s appointment. “If Governor Martin should see fit to appoint John H. Carter to this office the people will secure a careful, honest and courageous Sheriff, and one whom the lawless element yet remaining in the county have a wholesome fear,” decreed The Hartland Times.

“That gentleman has lived on his present farm ten years, and has succeeded, by careful management and industry, in making himself comfortable well off. During that time he has seen the country grow from a border territory, ruled by the cowboy, and occupied only by cattle and their owners, to its present thriving condition of handsome towns, farm homes, school houses and other evidences of advanced civilization. But such changes were not made without trouble, and though he himself engaged in cattle raising, John Carter was always in the front, protecting the rights of the weak settler . . . he has done the state signal service in arresting murderers and other desperate criminals, always at the risk of his life, and sometimes when human life had to be taken in order to protect law abiding citizens.”

This was a time of rampant hijinks and game play between towns vying for county seat and some shady characters vying for offices. Governor Martin appointed R.F. Thorne, not Carter, as the first Kearny County sheriff, but John Carter’s public service did not end there. He served multiple terms as a county commissioner, as an officer with the Hartland Republicans, school director for the Hartland school district, was undersheriff again in the 1890s, and was a member of the GAR, having served during the Civil War.

Born in 1844 at Collinsville, Illinois, John arrived in the Hartland area eight years before the town was platted. He built a homestead and filed a timber claim on his property which was adjacent to the townsite near Indian Mound and the famed Chouteau Island. Carter’s was the first timber claim proved up in the county, and the grove was a popular venue for early-day celebrations. Carter also ran a butcher shop and farmed. He and his first wife, Mary Penn Carter, had four children: Amy, Ezra, Hattie, and Alice who was the first girl born in this county. John Carter died at the age of 80 at San Diego, California in 1924.

SOURCES: History of Kearny County Vol. 1; Southwest History Corner by India Simmons; Buffalo Jones’ Forty Years of Adventure by Charles Jesse Jones; archives of The Hartland Times, Lakin Pioneer Democrat, Lakin Herald, Lakin Index, Western Kansas World and Topeka Daily Capital; Museum archives; and Ancestry.com. Special thanks to Charlotte Carter Isaacs, great-great granddaughter of John H. Carter.