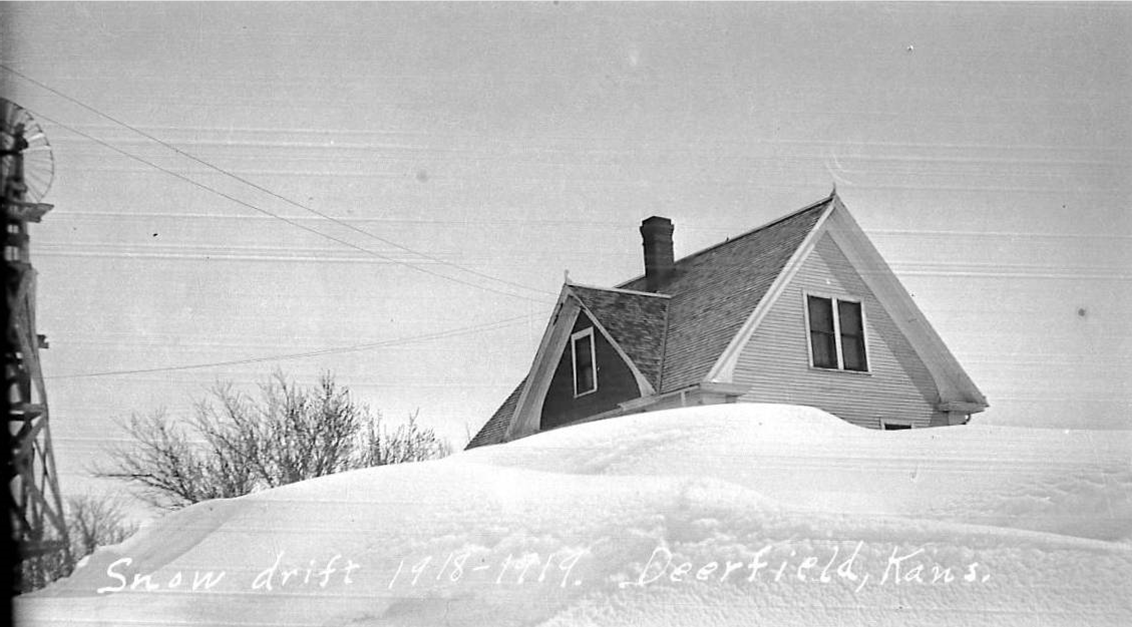

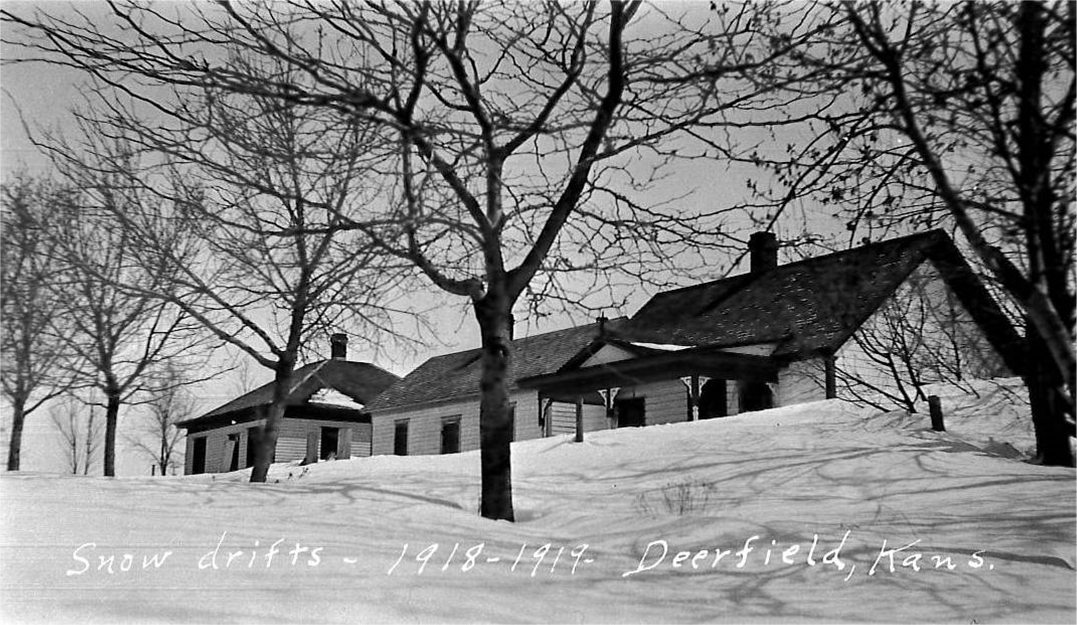

Weather forecasters predict arctic temps in the days ahead along with a chance for more snow, but Kearny County still has plenty of the white stuff left over from Monday’s blizzard. Just what kind of winter is in store for Southwest Kansas, and could it be reminiscent of the winter of 1918-1919? Snow blanketed Kearny County with a two-foot snow fall on December 16, 1918, and with temperatures averaging in the 20s, the snow didn’t go away any time soon. Oldtimers who had been here for 30 years or more claimed that they had never saw snow so deep.

On January 3, 1919, a reporter in the Prairie View area north of Deerfield reported that their neighborhood had been snowbound for two weeks with a foot and one-half deep snow and seven-foot drifts. Perhaps the saddest incident reported was the death of John Bender who lived north of Deerfield. The 35-year old father died of pneumonia after a bout with the flu. “When undertaker Nash reached there Sunday (December 29, 1918) there were four bad cases in the home and the father lifeless.” An effort was made two days later “to get a casket to the home and the trip was abandoned after a mile or two of the way covered.”

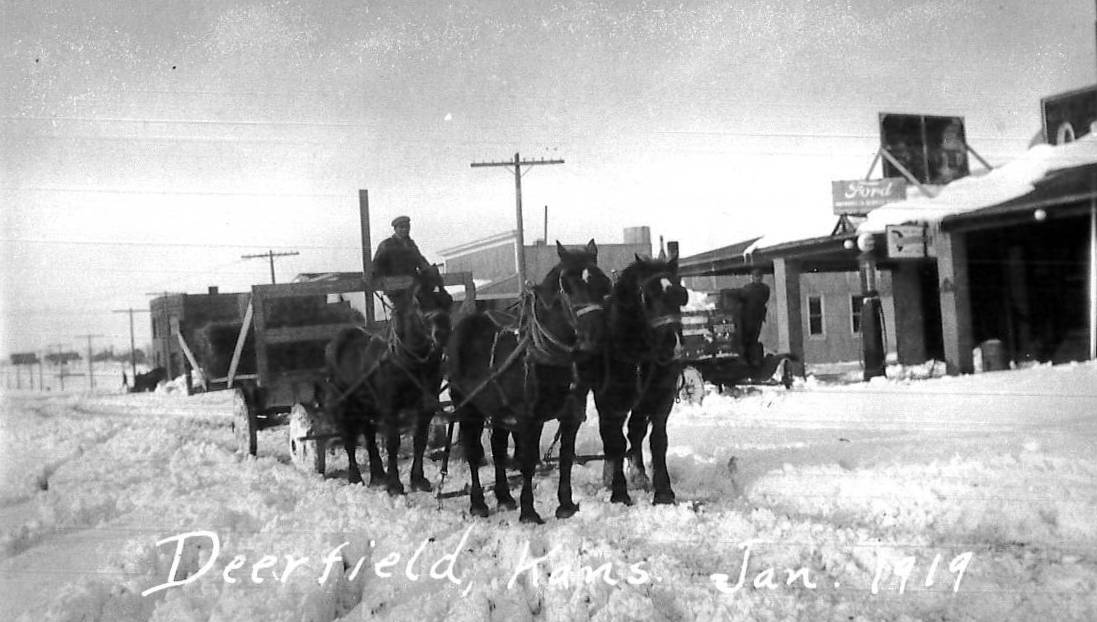

By January 10, the Advocate reported that the greatest problem in Southwest Kansas was getting feed to the stock, “and it is one of the busiest times our stockmen have ever experienced.” With many cattle to feed and no grass in sight, a large number of cattle were shipped to market and others were driven to the river where feed was shipped in. Four or five hundred tons of hay had been purchased in Colorado and was being shipped to Kearny County by rail which furnished some relief to anxious stockmen. Many tons of straw, alfalfa and cottonseed cake were shipped via the Garden City railroad to Wolf siding from eastern Kansas. Farmers constructed their own sleds of various sizes and shapes to transport feed to their livestock and bring coal home to heat with. With each issue of the paper came more news about horses and cattle dying or being thin and weak near death. Farmers made wooden scrapers and drags to bare the ground, and locals were eager to see the snow go. By January 24, the sentiment was “it is enough for one winter … it will take a lot of “Old Sol’s” heat to melt this deep snow.” Elsewhere in the January 24th Advocate was the report that Dr. Richards had walked eight miles from Deerfield to Lakin on account of his patients as the snow was still a handicap to travel out of broken paths.

Mail delays had become the norm, and at least one carrier abandoned his automobile and resorted to a team and buggy. On February 7, the Advocate reported, “We ascertained Saturday from a trustworthy source that twelve hundred tons of hay had been unloaded at this point in the past five weeks and one hundred tons of straw.” Fortunately, coal dealers had stocked up enough and were able to provide a steady supply of black diamonds to their customers.

“Four degrees above zero Sunday morning . . . we are promised a warm wave by the 18th. We hope it will be warm enough to melt the snow,” was the report in the February 14 Advocate from Prairie View. That same issue carried the news that “Herman Ladner was out riding in his car Sunday, the first car to run in the hills since the 18th of Dec..” On February 21, a Deerfield citizen reported that they still could only see “two or three bare spots of ground.” There were still students who were not able to get to school because of road conditions. “The long distance, mud, snow and slush make it a drudgery for many a pupil and teacher.”

Then came another snow. On February 28, the Prairie View reporter wrote, “We thought that last week, one more day of sunshine would make a finish of the snow, that fell the 16th of December, but on Tuesday night and Wednesday and Thursday, a rain started and wound up with six inches of snow, which seems in no hurry to leave us.” Many complaints were coming in to the county health officer of unburied cattle carcasses and other animals that had perished in the severe weather.

Spring-like days in mid-March, “assured us that the snow would soon be a thing of the past.” Snow in South Kearny had all disappeared except in a few spots where there were heavy drifts. The weather was looking fine, farmers were going to work listing and planting their fields, and the rural people were coming into town again. Mail carriers were once again able to complete their regular routes in a timely fashion. Thinking that winter was over, some ranchers moved their cattle to pastures that had no protection. The Prairie View Sunday School which had been closed since October on account of the flu and impassible roads was scheduled to begin meeting again on April 6.

Then, without warning, came a raging blizzard. The April 11 Advocate said that snow had started falling on Tuesday, April 8, “and up to the hour of going to press was still at it.” A reported 1,000 head of cattle in Kearny County were lost in the April storm alone. The late Henry Molz and his father, Adam, lost 112 head after moving 200 to their pasture two miles northwest of Lake McKinney just prior to the blizzard. In milling around, the cattle either pushed the fence over or packed the snow until they could walk over and drift to the Amazon Ditch. The first ones could not get out, and the rest walked over them. Twelve head drifted into the lake. The Molz’s gave the hides to skinners for removal of the carcasses. “Lydia has received the shock caused by winter number 2,” cried the April 25 Advocate. The report came from the West South Side that “dead cattle are to be seen any way you look, while going along the roads.” Stockmen started hauling hay, cake and chop again as the snow storm found a number of them somewhat short on supplies and weary of a repeat. All in all, an estimated 30% of the cattle in Kearny County were lost during the winter of 1918-1919.

SOURCES: Diggin’ Up Bones by Betty Barnes; History of Kearny County Vol. II; archives of The Advocate, Museum archives, and courier-journal.com.