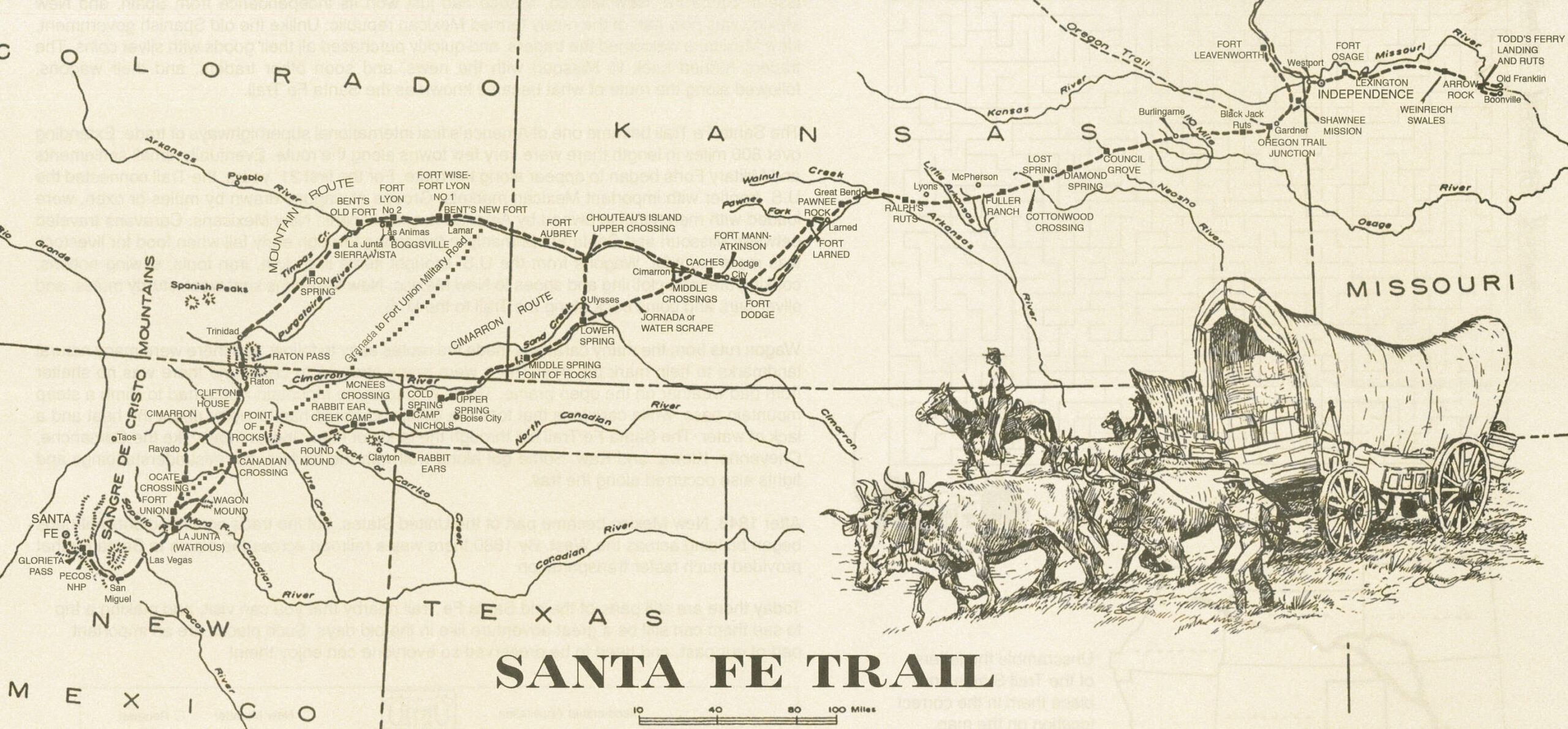

No one knows for certain just how many thousands of wagons journeyed along the Santa Fe Trail. The heavy cargo carriers often traveled three or more abreast, their wheels etching ruts that can still be seen on various sections of the Trail. Just north of Highway 50 and about three miles west of Deerfield lies Charlie’s Ruts, the site of several sets of parallel swales. This property, donated to the Kearny County Historical Society in 1984 by the late Paul Bentrup, is open to visitors. In fact, visitors are encouraged to walk in the time-smoothed tracks, and that is exactly what Bentrup hoped for when he deeded the property.

Walking in the ruts is a tradition established by Paul’s father and the site’s namesake, Charles Bentrup. When Charlie discovered the wagon swales on his land, he knew he not only wanted to preserve them but share them with the public. Before he died in 1956, Charlie made it known that he wanted the ruts to be made available to visitors for all time.

“That’s the way he wanted it, and that’s the way I want to keep it,” Paul said.

Paul was a faithful caretaker to the ruts and an avid promotor of the Santa Fe Trail. He kept a mailbox at the turnout for the ruts and kept it supplied with a variety of historical information and a notepad for people to sign. His car was always loaded with Trail information which he readily shared and used to recruit new members. In 1987, Paul was the first person recognized by the SFTA with an Ambassador Award. In 2015, he was posthumously inducted into the Association’s Hall of Fame.

The Santa Fe Trail is just one of many historic routes which have been recognized by Congress as national historic trails. Physical traces or remnants of these trails such as wagon ruts, graves, inscriptions and campsites can be found on state lands, in nature preserves, in city parks, on ranches, and even in suburban back yards. Many of those important pieces of trail history have been publicly commemorated, protected and preserved through the National Park Service’s partnership certification program.

In the fall of 2018, Charlie’s Ruts joined the list of Santa Fe Trail certified sites when the Kearny County Historical Society and Kearny County Commissioners entered into a partnership certification agreement with the NPS. The KCHS retains all legal rights to Charlie’s Ruts and is eligible to receive technical assistance, protection and site development guidance, project funding and assistance, and recognition through the park service. A PCA was also entered into between the NPS, KCHS and Bob and Adrian Price who own the land where visitors park and gain access to the ruts.

Bob Price also serves on the historical society board and installed the National Park sign at the ruts last year. The KCHS and Lakin PRIDE also collaborated on the installation of a silhouette at the site featuring a conestoga wagon pulled by two oxen and led by a lone rider on horseback. Clif Gilleland brought the idea for the project to the KCHS on behalf of PRIDE, and generous donations from the community provided the funding. At the 2023 Santa Fe Trail Symposium held at Independence, MO, both organizations were recognized with the Hathaway/Gaines Memorial Heritage Preservation Award for their efforts in preserving Charlie’s Ruts.

Most recently, the kansastravel.org website added a new page devoted to Charlie’s Ruts. Information and pictures can be seen not only on their website but also on their Facebook page.

There’s no doubt that both Charlie and Paul Bentrup would be very pleased with the attention that the ruts have been receiving.

SOURCES: National Park Service; archives of the Lakin Independent and Wichita Eagle; kansastravel.org; Facebook; and Museum archives.

Chouteau’s Island was the site of a number of skirmishes, and it was one skirmish in particular that earned the island its name. In the spring of 1816, Auguste P. Chouteau and his hunting party were returning from the upper Arkansas in Colorado with a winter’s catch of furs when they were attacked by a band of 200 Pawnee Indians. They retreated to the island where the grove of cottonwood trees, thick clumps of willows and a heavy growth of tall grass provided excellent coverage. Despite being considerably outmanned, Chouteau’s party successfully fought off their attackers. One man was lost and three others wounded.

In 1828, more than $10,000 of silver was buried at Chouteau’s Island by a group of traders known as the Milton Bryan Party. The group was on the return trip from Santa Fe, and among Bryan’s party was a man by the name of William Young Witt. Witt, a third cousin to the grandmother of B.C. Nash, a lifetime Lakin resident, kept a diary of the journey. One morning after arriving at the Upper Cimarron Springs, Bryan’s party was awakened just before dawn.

“The whole earth seemed to resound with the most horrible noises that ever greeted human ears; every blade of grass appeared to re-echo the horrid din,” Witt wrote. “In a few moments every man was at his post, rifle in hand, ready for any emergency, and almost immediately a large band of Indians made their appearance, riding within rifle-shot of the wagon. A continuous battle raged for several hours.”

After successfully stampeding all the horses and mules, the Indians retreated. Hitt was wounded six times. (According to Bryan’s account and Hitt’s son’s account, Hitt was wounded 16 times.) The next morning, some of the men took off in hopes to find the lost stock. Hitt was on his way back to camp when he was overtaken by Indians, but some of his traveling companions arrived in time to save him. Unable to secure any of their stock, the entourage left by foot in the morning with each man shouldering a rifle and a proportion of provisions. After eight days travel, they had less than 100 pounds of flour left and had been unsuccessful in finding any game.

Hitt recalled, “For two weeks the allowance of flour to each individual was but a spoonful, stirred in water and taken three times a day.” Adding to their futility was a scarcity of water. In desperation, the troupe was once compelled to suck the moist clay from a buffalo wallow.

As soon as a convenient camping ground was found, the men made shelter and left the weakest of their party while some of the strongest hunted. Successful at last in killing some small game and buffalo, they used buffalo chips to fuel a fire. After a few day’s rest, the men began again to march homeward, but their money had become a greater burden than they could bare. They decided to bury it at the first good place they came upon.

“We came to an island in the river to which we waded, and there, between two large trees, dug a hole and deposited our treasure…This task finished, with much lighter burdens, but more anxious than ever, we again took up our march eastwardly.”

Traveling for over two weeks by foot, the men were exhausted; some scarcely able to move. They divided company, the weaker ones to proceed by easier stages. When the stronger ones arrived at the settlement, they sent a party with horses to bring in their comrades who were seemingly nothing but human skeletons wrapped in rags, but “all got safely to their homes.”

The following year, the traders returned to Chouteau’s Island; however, Hitt is not mentioned as being among the group of men. Their party was accompanied by Major Bennett Riley and his men, the first military escort on the Trail. The silver was retrieved, and the trading party continued their trek to Santa Fe with their goods. South of the river was Mexican territory, and the American troops could go no farther. The traders began their journey down Bear Creek pass and were attacked by a band of Indians upon entering the sandhills. Nine of the men, riding at full speed, returned to the soldiers with the dreadful news. The troops disregarded their orders and made a hurried march across the river to defend the caravan. One trader, Samuel Lamme, lost his life in the assault, and his tortured and mutilated body was laid to rest at the edge of the hills not far from the Trail. Riley and his troops accompanied the traders for two more days and then reluctantly returned to Chouteau’s Island where they camped for three months awaiting the caravan’s return.

Between 1865 and 1870, a caravan of traders was attacked by Indians in the valley between Chouteau’s Island and Indian Mound. Word reached Fort Garland of the attack, and soldiers were sent to the scene. By the time they reached the area, the Indians had fled and the traders were all dead. The soldiers buried them and returned to Fort Garland. Legend has it that the burial ground was visible for many years as the grass there was much greener.

In 1941, Kansas was celebrating the 400th anniversary of the coming of Coronado to Quivira, the first white man to visit Kansas. The occasion was observed by placing historical markers all over the state. Kearny County held a Pioneer Day celebration that July, and a crowd of more than 1,000 witnessed one of the largest parades in Lakin where 10-gallon hats, cattlemen’s garb, pioneer costumes, horse riders and buckboards were abundant. Following a program at the court house, participants drove a mile west of Lakin on US 50 for more speeches, music, celebrating and the unveiling of the Chouteau Island marker. Although the original sign is long gone, a sign commemorating Chouteau’s Island can still be found just west of Lakin at the roadside park beside the golf course.

Photos from the 1941 Chouteau’s Island marker reveal. The island once rose lush and green in the middle of the Arkansas River, its disappearance blamed on natural forces, flood control measures and the use of the Arkansas for irrigation.

SOURCES: “William Y. Hitt Santa Fe Trail Memoires,” “The Old Santa Fe Trail” by Colonel Henry Inman, “Commerce of the Prairies” by Josiah Gregg, “The Flight of Time” by Milton E. Bryan, “Kansas Before 1854: A Revised Annals” compiled by Louis Barry, “Chronicle of Bennett C. Riley” by Leo E. Oliva; History of Kearny County Vol. 1, & ancestry.com. Special thanks to Meg Nash Spellman.

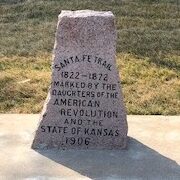

By 1900, the Santa Fe Trail was already history. If asked to locate the Trail, very few people could do so. The Kansas Daughters of the American Revolution, an organization which honors our American heritage, set a plan in motion in 1902 to mark the old commerce route as a tribute to the brave pioneers who traversed it. “Those early travelers prized the old Trail as a road to the future, and we hope the people of years to come will use it and keep its early history in remembrance.”

The DAR enlisted the aid of maps, the knowledge of early settlers, the Kansas State Historical Society and some previously erected markers to trace the route of the SFT. At a Trail Committee meeting in 1905, the Daughters decided to ask the school children of Kansas to contribute a penny each toward the marking of the Trail since the funds appropriated by the State were not enough to pay for all the markers. On Kansas Day 1906, which was also designated as Trail Day, approximately 200 pennies were collected from Lakin students to help in the endeavor.

In 1907, the DAR announced that 96 markers had been placed throughout Kansas. Kearny County’s markers arrived by rail in July of that year, and commissioners paid the expense of setting the five stones. Since Kearny County did not have a DAR chapter, County Clerk and Lakin pioneer F.L. Pierce gave prompt and efficient attention to the task of having the markers placed. The marker placed in Deerfield stands in the southeast corner of the city park. In Lakin, one monument was set at the old courthouse at the corner of Main and Waterman. This marker was moved to the current courthouse in 1939. The third marker in Lakin sits in front of the high school. It was moved to this location in 1961 but had originally been placed at the site of the school building which sat on the west end of the Lakin Grade School block.

Hartland’s Main Street was the location of the fourth marker. As Hartland gradually disappeared, the marker was engulfed in weeds. Billy Carter was cultivating the ground and put a long chain around the marker and pulled it over to his house. Later the DAR Chapter of Garden City secured the assistance of the highway commission and had the marker moved to the River Road where it intersects the once Main Street of Hartland.

The final marker was placed between Lakin and Deerfield at Long Schoolhouse. For several years after the school closed, the marker remained where it was placed by the side of the highway. As the story goes, a young man who was opening a filling station in Lakin thought the marker would look good on the station grounds and brought it to Lakin. Kearny County commissioners later instructed Paul McVey, county engineer, to move this marker to Indian Mound. Mr. McVey and Bill Fross accomplished this difficult task using a winch truck.

The dates engraved on the markers (1822-1872) are a somewhat controversial topic among trail enthusiasts as the Santa Fe Trail Association recognizes the start of the trail as 1821 when William Becknell first ventured to Santa Fe and the end of the trail as 1880 when the railroad reached Santa Fe. The Story of the Marking of the Santa Fe Trail by the Daughters of the American Revolution in Kansas and the State of Kansas claims, “The earliest use of the Trail was in 1822, when a caravan left Boonville, Mo., by way of Lexington, Independence, Westport (now Kansas City, Mo.), thence in a southwesterly direction across the great State of Kansas, then only a desert and wilderness, and on to Santa Fe, New Mexico.” The DAR correlated the end of the trail with the completion of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad through Kansas in 1872. In 1996, a plea was made in the quarterly newsletter of the Santa Fe Trail Association to press for historical accuracy, but the original engraved dates remain. Nonetheless, more important than the dates on the granite markers is the fact that had the Daughters not marked the historic route when they did, the location of the Santa Fe Trail could have been lost forever.

SOURCES: “The Story of the Marking of the Santa Fe Trail by the Daughters of the American Revolution in Kansas and the State of Kansas” by DAR Historian Mrs. T.A. Cordry; “History of Kearny County” Vol. I; Kansapedia, Kansas State Historical Society, www.dar.com; www.santafetrailresearch.com; archives of the Advocate; Museum archives, and information provided by the late Marcella McVey.

Images of a gun-slinging, rough-riding bandit generally come to mind when hearing the name “Jesse James,” but Kearny County’s Jessee was a kind neighbor and devoted father. The son of a Civil War doctor, he was married to his father’s younger half-sister according to Ancestry.com and Find a Grave records.

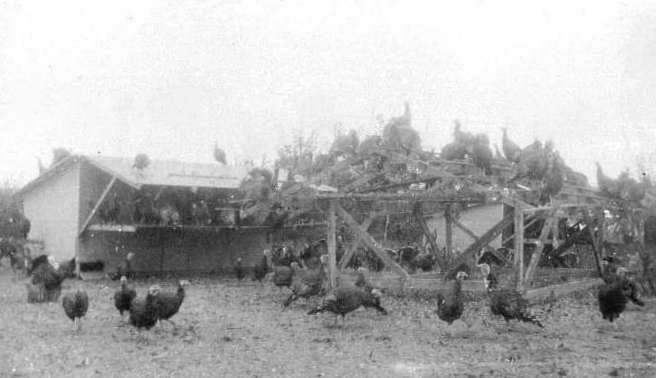

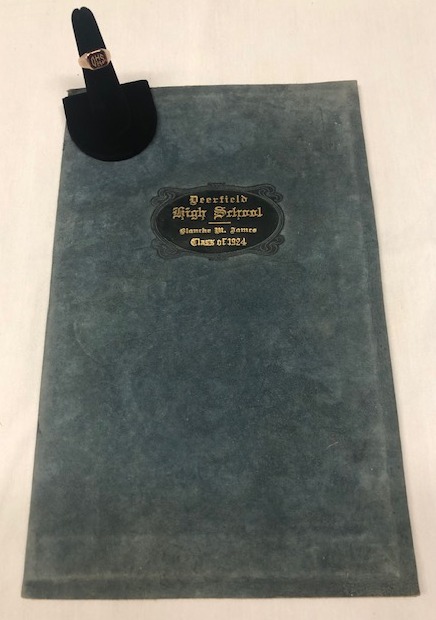

Jessee was born in 1860 to William “Doc Billy” and Phoebe (Perkins) James at Van Buren, Arkansas. At Fredonia, KS in 1881, he married Nancy Ann Priscilla James, the daughter of Jesse Ballard James and his second wife, Elizabeth Campbell. Jessee and Nancy’s first child, a daughter named Della, died two days after her birth in Bourbon County, Ks. Son Homer was born in Kingman County in 1884, and daughter Maybelle was born about 18 months later in Edwards County.

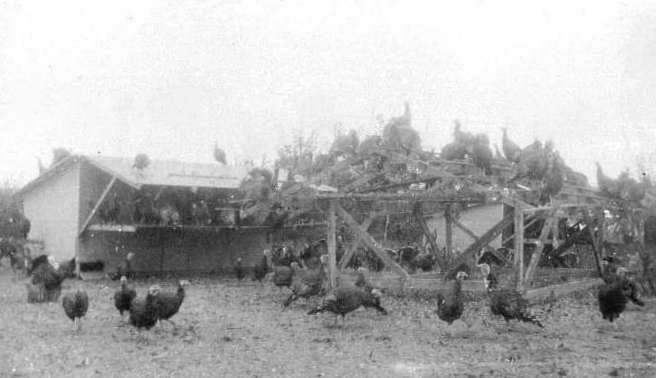

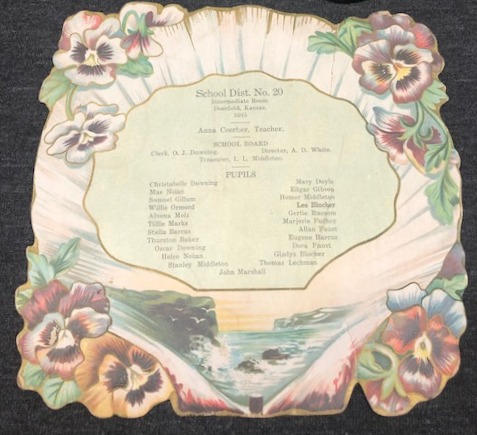

After hearing stories of how one could file on a homestead and tree claim, prove up, and gain ownership to several acres of land Out West, the James family decided to try their luck at a new location. In early March of 1886, they loaded their belongings into, on and around the sides of their prairie schooner, and Jessee, Nancy, Homer and baby Maybelle made their way to the north flats of Kearny County. They settled on the southwest quarter section of 12-22-36 with their two mules, two cows, a calf that was born on the journey west, 12 pigeons and their shepherd dog, Tige. The wagon was unloaded, and the wagon box with its bows and cover was set on the ground to serve as a hut for the family to stay in until a small home could be built. Instead of being covered with grass, the prairie was burned off black, supposedly by cattlemen trying to dissuade settlers. One of the first tasks at hands, besides building a dwelling, was to dig a well.

Sons Thurlow and Roscoe were added to the family in 1887 and 1890, respectively. Then, in 1893, the family moved to Jessee’s tree claim on the northeast quarter section of 4-22-36 so that the children could attend Columbian (later Columbia) School. Not yet five years old, Thurlow died in 1902 and baby Sula was born four months later. Water was hard to come by on the flats, and pioneer life was riddled with trials. The James’s saw many of their neighbors leave the area, but they pressed on. Jessee provided for his family by raising stock and farming. He also did occasional teamwork for neighbors who didn’t have the means to come to town and pick up necessities for themselves. Jessee served on the District 7 school board for 11 years and was serving on the Hibbard Township board at the time of his death in February of 1904. He had come to Lakin a few days earlier to secure necessary supplies for two of his children who were seriously ill, caught a cold and died of pneumonia at the family home.

After Jessee’s death, Nancy James homesteaded the northeast quarter section of 9-22-36. In 1905, she moved with her children to this land where the family could have an abundance of water without having to haul it. Nancy never remarried and died in 1946.

Homer and Maybelle filed on nearby homesteads when they reached the eligible age. Homer married Stella Hutton in 1910, and during 1911 and 1912, he worked in Wyoming as a cowboy on the TE Ranch which belonged to Buffalo Bill Cody. Later the family moved to New Mexico and then to Colorado where Homer succumbed to the Spanish flu in 1918. Stella returned to Lakin with the couple’s two children, Gaylord and Della (later Mrs. Glenn Anschutz). Two-year-old daughter Lena had died in 1914.

Roscoe James married Frances Wilkinson in 1910, and they lived for a time at Winfield, Kansas before moving to Colorado in 1923. The couple had 12 children, two of whom died in infancy. A retired carpenter, Roscoe was living at Pueblo when he died in 1963.

Maybelle became a teacher and lived for many years on her homestead just three miles west of her childhood home in Hibbard Township. She was married to Rudolph Gropp in 1911, and they moved into Lakin just a few years prior to Rudy’s death in 1969. Maybelle remained in Lakin until the mid-1980s when she went to live with her daughter, Elizabeth, in West Fork, Arkansas. Maybelle died in 1989 at the age of 103. She and Rudy’s son, Jesse Samuel, was living in California at the time of his mother’s death.

Sula James, also a teacher, married Arthur Mace of Wichita County in 1928. They started a sheep operation and moved in 1952 to Colorado where the water supply was better. After Arthur’s death in 1970, Sula returned to Lakin and made her home with Maybelle in a modest bungalow on Hamilton Street. She lived there until entering High Plains Retirement Village in 1990 and died at the age of 88 in 1991. Sula and Arthur’s only child, a daughter by the name of Nancy Ellen, died in infancy.

The story of Jessee James and his family is not unlike those of the other pioneers who ventured west and lived lives of hard work, courage, tribulation, and perseverance. None of Jessee’s descendants remain in Kearny County; nonetheless, the family is important to our history. Maybelle and her husband were charter members of the Kearny County Historical Society, and Maybelle recorded and shared a great deal of local history with the society. The Columbia Schoolhouse on Museum grounds was a gift from her to our entire community.

To know Maybelle and Sula was a gift in itself. As a little girl who lived just two doors away, this writer spent many a Saturday morning at their home hearing stories of their life on the Kansas plains and songs of old while watching the sisters tat, bead, crochet and more. They were fascinating, kind and joyful women who helped fuel the love of local history that courses through my veins.

SOURCES: History of Kearny County Vol. 1; Diggin’ Up Bones by Betty Barnes; Find a Grave; Ancestry.com; Museum archives and archives of the Lakin Independent and Advocate.